Recently, Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) premiered on Showtime and at Festival de Cannes (as the second TV series in the history of the festival). So far, the new Twin Peaks has had lackluster Nielsen ratings, but record-breaking numbers in terms of streaming on Showtime and sign-ups for Showtime’s streaming services (e.g. Showtime Anytime and Showtime on Demand). In terms of style and content, the new Twin Peaks is radically different from the original series, and it includes abstract references to different David Lynch productions while combining familiar faces and places with new situations, stylistic choices and characters. In many ways, the new series is about “returning,” about going back and trying to re(dis)cover or even recreate Twin Peaks, but the revival is not a nostalgic revisit to a cozy, All-American small-town. “I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

When David Lynch received a several minute long standing ovation after the premiere of the new Twin Peaks (Showtime, 2017) at Festival de Cannes, it was seen as a revival of the director (who had received mixed reactions and reviews at the same festival in 1992) and a mythological return to Twin Peaks (fig. 1).

In many ways, the new Twin Peaks is about returning, about going back, re(dis)covering or even recreating a town and a mythology from the scattered fragments of familiar faces, vague memories and incompatible or even incoherent sources. “What we observe is not nature itself,” as Annie Blackburn (Heather Graham) said to Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) in the original series, quoting Werner Heisenberg, “but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” That line might hold a deeper truth in the world of Twin Peaks than we had previously thought: Perhaps there is no one Twin Peaks, just as there is not one Laura Palmer or only one Dale Cooper.

In other words, if Twin Peaks seems unrecognizable, disorienting or even incomprehensible in its new incarnation, there might be a good reason for that: As of yet, we have only seen the town in fragments, Dale Cooper, who is, himself, as fragmented as ever, has not yet returned to Twin Peaks, and the town and FBI agent that we came to love in the early 1990s might look different from a new perspective. In the original series, Cooper famously insisted on seeing Twin Peaks as a piece of “heaven,” even if that heaven “included arson, multiple homicides, and an attempt on the life of a federal agent” (as Judge Sternwood reminded him).

In the new Twin Peaks, the good old FBI agent and the cozy American small-town both look different, and both are torn into fragments that we, the viewers, have to investigate and re-assemble, before we can ever really “return.” First, though, we need to accept the fact that this is not the same Twin Peaks we left more than 25 years ago: Like the prequel Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), which began with a metaphorical shot of a TV set being destroyed by a blunt object, this is a new iteration of Twin Peaks, not a simple addendum to the original series or a linear continuation (fig. 2). More likely, this is a new layer to a multilayered story and universe, and only when we have seen all the different perspectives and layers will we (perhaps) know what Twin Peaks really was and who Dale Cooper and Laura Palmer really were. At least until Mark Frost’s tie-in book, The Final Dossier (2017), comes out and potentially disrupts our understanding of Twin Peaks once again.

This article explores the first four parts of the new Twin Peaks, focusing on the strategies and secrecy surrounding the new series, the combination of old and new, and the expansive nature of the Twin Peaks storyworld, now including fragments, faces and motifs from Lynch’s earlier productions. The article also interweaves comments from different cast and crew members – editors Duwayne Dunham and Jonathan P. Shaw, sound supervisor and re-recording mixer Ronald Eng, actors Chrysta Bell and Wendy Robie, director of photography Peter Deming, and co-creator Mark Frost – who talked with me about returning to Twin Peaks and working on a TV series in a new era and a more liberal and auteur-minded production context.

Lynching Television: Not-TV Branding and Auteurism in The Return

It is always best if there is one controlling creative force. In this case, it was David Lynch, and he always brings a very unique perspective. [However] David and Mark are like peanut butter and jelly, each unique and on their own quite tasty. But put them together and you have something special.

Duwayne Dunham, editor of Twin Peaks: The Return (Halskov 2017c).

David Lynch is known for being brief and somewhat cryptic when talking about Twin Peaks (just think of his recent “breakdown” of the new Twin Peaks in Entertainment Weekly, cf. Jensen 2017a), but this time he has been clear as a bell: The new Twin Peaks is not a traditional continuation of the original series (ABC, 1990-1991). We should think of it as an 18-hour movie, divided into different “parts,” not as a new “season” of a television serial.

“This was more like a gigantic film, a TV show in a feature film format,” as additional editor Jonathan P. Shaw told me. “It is very unlike anything I had ever worked on in television. It challenges the audience, and there’s some work to be done for the viewers, but it will pay off for you” (Halskov 2017b).

The new Twin Peaks is called The Return, and that title (which was conjured up by CBS/Showtime, not David Lynch and Mark Frost) refers to Dale Cooper’s attempt to return to the town of Twin Peaks, but it also indicates that we are witnessing a return of David Lynch and his signature style. Stylistically, at least, this is as similar to Lynch’s paintings and movies (e.g. Eraserheads [1977], Lost Highway [1997], Mulholland Dr. [2001] and Inland Empire [2006]) as it is to the original Twin Peaks, and we are closer to the abstract version of Twin Peaks that we witnessed in Episode 29 and Fire Walk with Me than to the groundbreaking, but relatively conventional, pilot episode (which premiered in April, 1990).

“A pattern is forming”

The first time we see the famous chevron pattern known from The Red Room in Twin Peaks is actually in the opening of Eraserhead (1977), David Lynch’s first feature-length film. In Eraserhead, the floor of the lobby in Henry’s apartment building has the same kind of pattern, and once we have recognized that pattern, we will notice it virtually everywhere in the original Twin Peaks, often directly connected to Laura Palmer’s tragedy. We notice it on the principal’s jacket when he announces Laura’s death in the pilot episode; we notice it on Leland’s jacket when he dances with Laura’s homecoming queen photo; and we see it on a blanket during the pivotal scene from Episode 14 where Madeleine Ferguson is brutally killed (fig. 3-7).

This is but one example of the many patterns, repetitions and reflections in Twin Peaks (just think of the ending of Episode 29 which not only deals with doubles, but actually ‘duplicates’ the ending of Mario Bava’s film Operazione Paura [1966, Kill, Baby, Kill] and two paintings by René Magritte: “Portrait de Paul Nougé” [1927] and “La reproduction interdite” [1937]). And when the new Twin Peaks begins with a black and white sequence with an expressive use of lighting, sound and long pauses, we immediately think of Eraserhead. Particularly, we think of Eraserhead when we hear The Giant’s line to Cooper, “Listen to the sounds,” and when we notice the intentional discrepancy between the visual motif – a record player – and the sound (this time Carel Struycken’s character is called ???????). Metaphorically speaking, this mismatch between the sounds and the images might reflect the fragmentation of Cooper’s character. Something is off, something does not fit (fig. 8-9).

However, as Jonathan P. Shaw says, “David Lynch is a master of sounds and visuals, who works on a deeply visceral level,” and he creates moods and atmosphere before ever thinking, let alone speaking, of meaning and symbolism.

In the original Twin Peaks, “there was always music in the air,” but in The Return Angelo Badalamenti’s iconic music is subdued or even absent (at least so far), and we notice a much more tactile, cinematic sound design (as we might already have heard in the title sequence which not only looks different, but also includes sounds of the waterfall) (fig. 10).

“David seems to like sounds that are organic,” as re-recording mixer Ronald Eng puts it. “He likes the sounds of wind, fire and water – things that occur in nature. That being said, he also loves the sound of electricity” (Halskov 2017d). Lynch creates a rich world of different sonic textures (organic sounds and non-organic sounds, sounds of old technologies and sounds of new media), and noises often produce an eerie sense suspense, while serving different narrative functions (the sound of electrical noise and short-circuiting, for example, seems to illustrate that we are “between two Worlds”). “Twin Peaks was one of the first projects of my career where we actually had enough time,” says Eng. “David had time to mix, to go back and listen and to get everything just right. I just hope people will like it because it is so different. It is not formulaic, and it will make you think” (ibid.). If we want to hear and revisit the old Twin Peaks, Mark Frost and David Lynch are intentionally refusing to “appease” us, as Corey Atad wrote in Esquire (Atad 2016).

In any case, the black and white sequence from the opening of The Return is markedly different from the aesthetic in the original Twin Peaks, but, ironically, the use of black and white photography is reminiscent of The Black Lodge as it was originally envisioned by Mark Frost, Harley Peyton and Robert Engels (in the script from Episode 29 that David Lynch famously chose to abandon). The visuals are closer to Eraserhead and Lynch’s early artworks (cf. Davis 2017), and the sound design bears a striking resemblance to Eraserhead and some of Lynch’s later films, especially Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Dr. (2001) and Inland Empire (2006). We recognize the record player as a visual motif from Eraserhead and Inland Empire, and we remember the record player from Jacques Renault’s cabin in the woods and from the horrifying scene in Episode 14 where Maddy is brutally killed, while a record player is heard in the background (in a combination of realtime and slow-motion).

Familiarity and Defamiliarization

Habitualisation devours work, clothes, furniture, one’s wife and the fear of war…. [A]rt exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony…

Victor Shklovsky.

In two of the official teasers which were released by Showtime before the premiere of The Return, we saw some “Familiar Places” and some “Familiar Faces” (from the original Twin Peaks and Fire Walk with Me).

Apart from giving us small pieces or fragments of information, these teasers pointed to a general combination of old and new in Twin Peaks: The Return, and to the way in which it combines familiarity and defamiliarization.

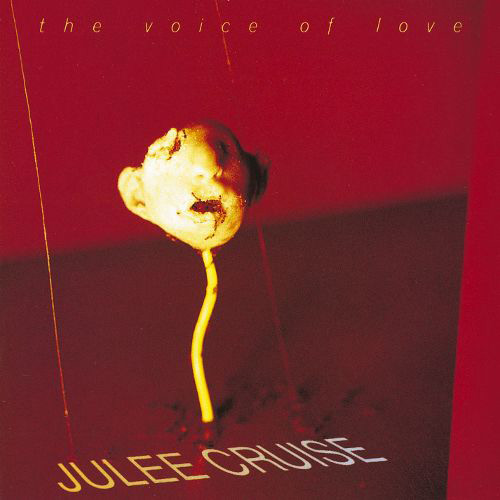

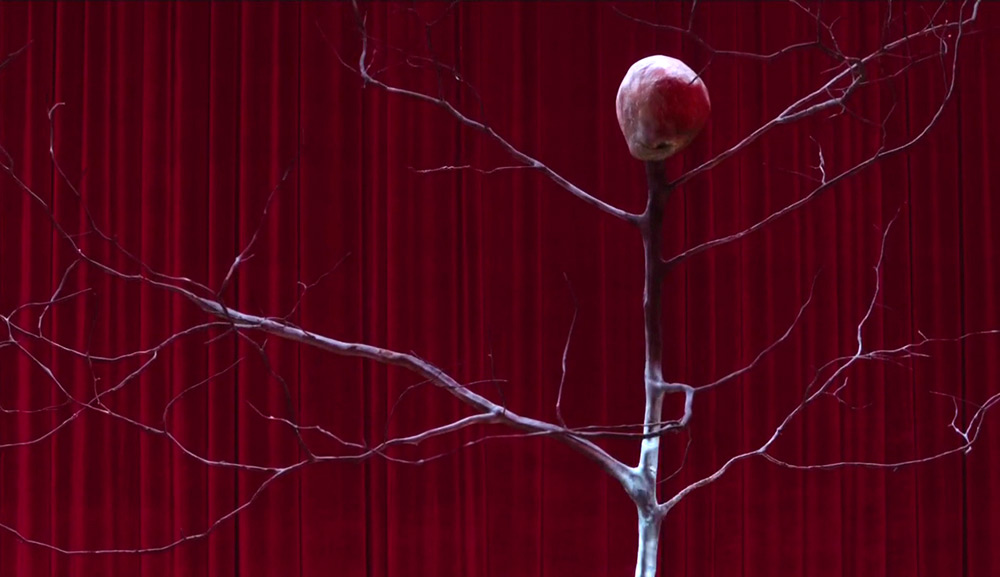

In an elegant way, The Return connects the world of Twin Peaks to the greater oeuvre of David Lynch by referring to some of his paintings, visual and sonic elements in his different films, and even to the cover art on Julee Cruise’s album The Voice of Love (1993, produced by Lynch) (fig. 11-12). In that sense, it might be reasonable when Jack Brandon of The Michigan Daily describes the new Twin Peaks as “Lynch unbound” (Brandon 2017), even if he, thereby, seems to underestimate and underemphasize the role of Mark Frost (more astutely, perhaps, Tal Rosenberg [2017] calls it a “bizarre and brilliant retrospective … of Mark Frost and David Lynch’s careers”).

The new Twin Peaks includes familiar faces in the form of old actors who “return” (clearly having aged), but also actors from other Lynch productions (Balthazar Getty, Patrick Fischler, Naomi Watts etc.) that show up in new roles (often strikingly or even uncannily similar to roles they have played before) and actors that were part of the original Twin Peaks but who return in new roles or credits (e.g. Phoebe Augustine [Ronette Pulaski] who plays American Girl in Part 3, and Walter Olkewicz who played Jacques Renault in the original series, but who plays a new bartender in the new series by the name of Jean-Michel Renault, referring to The Patty Duke Show [ABC, 1963-1966] and the concept of identical cousins).

There are also specific scenes that allude to Mulholland Dr. Just think of the funny scenes with the large woman and her small dog. And what about the impressive drone shots of New York and Las Vegas where the camera movements and the sound design are directly reminiscent of Mulholland Dr. – a film, mind you, that was originally envisioned as a spin-off of Twin Peaks, focusing on Audrey’s trip from the Pacific Northwest to Hollywood. These connections are hardly coincidental, and the sound design on the new Twin Peaks is created by David Lynch, Dean Hurley and Ronald Eng (who worked on Mulholland Dr. and Inland Empire), while the cinematography is created by Peter Deming (who was DP on Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr.).

I asked Deming about the use of lighting in the works of David Lynch, and I asked him whether or not they felt restricted when creating the new Twin Peaks, having to conform to a different medium and perhaps have to cater to a broader audience. As Deming said,

David and I never really talk about lighting, we talk about mood mostly. I’ll talk with David about the mood of the scene, and he’ll give me some very broad ideas, saying “today it’s sunny out” or something like that, and it’s really all about mood. When doing Mulholland Dr., we sort of had a short-hand from Lost Highway as to how dark it could be. There’s dark, there’s dark and there’s darker than dark.

As far as shooting the new Twin Peaks, there was never a discussion whether this was appropriate or not for television. But David is a special case here, and he has always been a special case. Going back to the original version of Mulholland Dr. – when it was a pilot meant for television – we were forced into a different aspect-ratio, and that was okay, since it was the standard of television back then, but in terms of lighting and composition David did not adhere to any standards or norms of television.

David was a painter before he started doing films, and he is always thinking in terms of images.

Halskov 2016a.

More specifically, there are scenes in the new Twin Peaks that are almost lifted from Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr., and there are scenes in the new series – and in the official teasers – that look eerily Lynchian. One example is the story of Bill Hastings (who is accused of murder) which seems to mirror the Kafkaesque story of Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) in Lost Highway, and a scene with Patrick Fischler (known from Mulholland Dr.) immediately takes the viewer back to a famous scene with Mr. Roque in Mulholland Dr. (fig. 13-15).

On a more general level, there are some shots of Dale Cooper being enveloped by darkness, and these shots seem iconically Lynchian, pointing to the dark story of Cooper, but also hinting at the blurred boundaries between different places and different realms. Before The Return had officially premiered on Showtime, I asked Peter Deming about this particular type of shot, referring to Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr., but also mentioning Lynch’s earlier works (e.g. Blue Velvet [1986] and The Grandmother [1970], fig. 16-18).

You are right, there are many scenes in David Lynch’s films where we see the faces of characters totally enveloped by darkness, and sometimes they are not pre-planned. In the case of Lost Highway, however, we made a very conscious decision to not light up the background in a few scenes. There’s a mystery to that total darkness behind a character and an uncanny sense of uncertainty or danger.

Ibid.

Other scenes allude to Eraserhead (cf. the shot of Major Briggs’ head which is seen floating in space in the third part of the new series), Blue Velvet (cf. the Rancho Rosa sign in Part 4 and the boys who play catch in Part 11, only to stumble upon a mutilated woman in grasse), and Wild at Heart (cf. the scene where Sarah Palmer [Grace Zabriskie] is watching wild animals on television, echoing a scene with Harry Dean Stanton from Wild at Heart and pointing to the general use of animalistic sounds and images Lynch’s films) (fig. 19). And some of the lines and motifs in The Return even connect with other parts of the Twin Peaks storyworld. For example, the One-Armed Man’s question “Is it future or is it past?” echoes a line from The Missing Pieces (2014) – a film that was made up of deleted scenes from Fire Walk with Me – and fans and scholars have found some even more hidden or obscure references to different tie-in books. The podcasters from Bickering Peaks have noticed a connection between the character Dougie Jones (Kyle MacLachlan) and lines from Scott Frost’s The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper (1991), Twin Peaks fan Kathryn Beckett has found direct references to Jennifer Lynch’s novel The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer (1990: 127) where the lines “I DON’T NEED ANYTHING. I WANT THINGS” are ascribed to BOB, and the story of Deputy Hawk (Michael Horse) and his heritage seems to resonate with Mark Frost’s tie-in book The Secret History of Twin Peaks (2016) (cf. Lynchland 2017 and Rezayazdi 2017).

The new Twin Peaks might seem very disorienting and fragmented to some viewers (partly because of the many different, seemingly unrelated locations), but that is true of most David Lynch productions, and it might subjectively reflect Dale Cooper’s feelings of being disoriented. We are struggling to find a path and a sense of place in the new Twin Peaks, just as Cooper is struggling to come home.

One of the new actors and performers in Twin Peaks, Chrysta Bell (Agent Tamara Preston), told me about this combination of the familiar and the unfamiliar in the works of David Lynch, and while she did not talk directly about Twin Peaks, her words resonate beautifully with The Return:

When watching a David Lynch production, you’re forced into something that is so far away from your realm of experience, but at the same time so familiar. It’s so familiar, yet so uncomfortable. It’s discomforting, yet we’re putting ourselves through it on purpose. We’re drawn to it, we’re looking for it, and I think it is a testament to his art. Recently, David Nevins compared Lynch to heroin, and I get it. You’re drawn to his art, curious about your own discomfort, and then you’re drawn to the characters, the music and the mood. It’s so addictive.

Halskov 2017a.

”We live inside a dream”

Another storyline that seems to allude directly to Mulholland Dr. is the one where Dougie Jones (Kyle MacLachlan) comes home from the casino with all of his winnings (perhaps Dougie Jones is a reference to the actor Doug Jones, known as “the man of 1000 faces, cf. Rossi 2016). In a playful, metafictional manner, that scene alludes to Mulholland Dr., and the way that Naomi Watts (Dougie’s wife) reacts to his winnings seems almost intentionally stagy (fig. 20). Is this reality, one might wonder, or are we “inside a dream”? Is the acting style intentionally off, just as the strangely artificial look of The Black Lodge (where the colors are slightly off – perhaps to illustrate a different state of being or level of existence – and digitized in a strangely inauthentic manner) and the somewhat corny visual effects in the jackpot scene?

The old Twin Peaks combined mystery, horror, comedy and melodrama, and was largely built on a conscious soap opera structure, including a fictional soap opera (Invitation to Love) within the world of Twin Peaks. The new Twin Peaks seems less soapy, as it were, and while it thrives on the kind of “competing moods” that we also experienced in the original Twin Peaks and many of Lynch’s other Works (cf. Halskov 2015), the different genre elements have been largely separated in the first four parts (where Part 2 exploits a horror-like use of suspense and shock, where Part 3 is a surrealistic voyage into another world, echoing Dune [1984] and Inland Empire, and where Part 4 looks almost like an absurd comedy, only to shift tone and mood at the very end) (cf. Bocko 2017). It might not have a metafictional show within the show (even if Jade [Nafessa Williams] might be an intratextual reference to the eponymous character from Invitation to Love), but there are motifs and scenes that are consciously stagy and metafictional in a similar way.

The scene with Wally Brando (Michael Cera) is a funny example of the staginess in ‘new’ Twin Peaks, combining corny 1:1 references to Marlon Brando with pseudo-existential lines delivered to the camera in a strangely stagy manner. In that scene, Cera is “talking like The Godfather” and looking “like The Wild One,” as Sean T. Collins puts it (Collins 2017). And the scene where Sam (Ben Rosenfield) and Tracey (Madelina Zima) watch the glass box might be seen as a metafictional reference to the viewers of Twin Peaks who watch intensely, often waiting for something to happen and unaware of the purpose and intention. The British scholar Ross Garner has referred to the glass box as a “pseudo-screen,” and he argues that the entire scene between Sam and Tracey is an example of what Kim Akass and Janet McCabe have called the discourse of the illicit (referring to cable television and not-TV branding). In Garner’s words:

Whilst this imagery [graphic nudity] was ‘new’ for Twin Peaks, it also felt like the series negotiating its institutional context by intertextually locating itself within long-established trends via shows like The Sopranos (HBO 1999-2007) and Sex and the City (HBO 1998-2004). The message communicated was ‘It’s not old Twin Peaks, its Showtime’s Twin Peaks’.

Garner 2017.

Similarly, David Lynch, in his metafictional role of Gordon Cole, admits to Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) that he does not “understand” what is going on, as if to funnily comment on the viewer’s potential confusion.

In the same way, when Denise Bryson (David Duchovny) muses on the phrase “Federal Bureau of Investigation,” it reminds the viewer of The X-Files (Fox, 1993-2002, 2016-) – which, in itself, borrowed from the original Twin Peaks – and when Bobby (Dana Ashbrook) cries intensely upon seeing a photo of Laura Palmer, it reminds the viewer of Dana Ashbrook’s role in the funny Twin Peaks tribute from Psych (USA Network, 2006-2014).

And what about the great ending of Part 2 where Shelly Johnson (Mädchen Amick) looks at James Hurley (James Marshall), saying “James is still cool. He’s always been cool,” as if to correct the many haters who have written critically and patronizingly about Marshall’s character (fig. 24).

In a metafictional way, the new Twin Peaks combines old and new, authenticity and artifice, and in many ways Dale ‘Eraserhead’ Cooper’s journey to recover or recreate himself reflects the series’ attempt to define itself as both a continuation of Twin Peaks and an independent work of art. As Jeff Jensen poignantly puts it:

Cooper’s odyssey to recover the fullness of his unique identity — or not — in an alien landscape filled with people who confuse him for being someone else or want him to be something else is compelling, in part, because it plays to, and with, our nostalgia. It’s a metaphor for the new Twin Peaks itself, a show that, for now, wishes to behave more as a new life reincarnation than a reboot or revival of a dormant old one. Cooper contains the questions, ambitions and restlessness of its creators. What should Twin Peaks be in 2017? How to satisfy themselves and the audience? By mimicking the original? By being radically different?

Jensen 2017b.

“Is it future or is it past?”

When the One-Armed Man (Al Strobel) talks with Dale Cooper in The Black Lodge, he asks him, ”Is it future or is it past?” This sentence echoes Fire Walk with Me which also disrupted and disturbed our natural sense of time and place in Twin Peaks. After the release of David Lynch’s prequel, the boundaries between past, present and future and dream, fantasy and reality became more fluid, and in the new Twin Peaks those boundaries are almost liquid (the Dougie storyline, for example, seems strangely unrealistic or dream-like, and the Rancho Rosa sign may be a metafictional reference to the eponymous production company behind the new Twin Peaks or a reference to the 1936-movie Rose of the Rancho).

The distribution of The Return is interesting in itself, and the fact that four parts were made available almost simultaneously, after which we need to wait until June 4 (US time) for the next part, could indicate that the first four hours are somewhat self-contained. That they function as a sort of prologue to the actual action, as a dream, a fantasy space or even a parallel universe (not unlike the Deer Meadow sequence in the beginning of Fire Walk with Me). In that sense, the fragments might also gradually begin to form a plot (in a more traditional sense), as we begin to ‘return’ and as Dale Cooper begins to find or re(dis)cover himself.

Perhaps, though, we will learn that there is no one Twin Peaks, just as there was no one Laura Palmer in the original series. In a very interesting audiovisual essay, Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez-López (2016) convincingly argue that the original series was subjective in its style, not realistic, inasmuch as there were two recordings of the tape that Laura (Sheryl Lee) sent to Dr. Jacoby (Russ Tamblyn). In the diegetic world of Twin Peaks, there is only one tape, but when we hear the same tape in two different scenes, across different episodes, the sound is markedly different, as if to mirror the different understandings and experiences of Laura. When Dr. Jacoby listens to the tape, Laura seems vulnerable, on the verge of tears, as if she desperately needs him, but when James (James Marshall), Maddy (Sheryl Lee) and Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle) listen to the tape, Laura sounds harsh and patronizing (perhaps fitting James’ understanding and relieving his feelings of guilt after having fallen in love with Donna). One version of Laura Palmer is also seen in The Return, and perhaps we will see new doubles of Laura and new uncanny repetitions of Laura’s tragedy (a tragedy that was replayed and re-enacted in endless variations in the original series).

In the same way, we might come to learn that Twin Peaks is not one place, but different places to different people, and if we ever truly return to Twin Peaks, we might return to a place that looks like the original town, but with some uncanny differences.

We might also learn that Twin Peaks, which was originally “filled with beautiful women” – young and pretty faces – is now a different town with torn-down buildings and “broken beauty” (cf. Jerslev 2017). The scenes with Sarah Palmer (Grace Zabriskie) and The Log Lady (Catherine Coulson) seem to indicate that, and the scenes with Coulson look almost like a touching intra-diegetic eulogy (fig. 25-26). In a similar way, the entire Dougie storyline might be seen as a sad reflection of this transformation theme, as Justin Lafleur has suggested, reminding the viewers of Twin Peaks actor Warren Frost (Mark Frost’s father) who died in February 2017 after struggling with Alzheimer’s disease.

A combination of nostalgia and radical ‘newness,’ Twin Peaks: The Return includes old footage, beautifully restored and included in a seamless way, and new characters (some of whom are brought in from other David Lynch productions).

Structurally, it is very different from the original series, and the different parts of The Return are more self-contained than in the original series (though in a way that is very dissimilar to sitcoms and traditional episodic television). In that sense, the songs at the end of each part might function as a sort of narrative glue or a nostalgic sense of “return,” and they look like a strange marker of seriality (coming around the hour-mark and typically ending an episode), though David Lynch has repeatedly defined The Return as a “film.” But that return in itself seems surreal, inasmuch as the venue looks different and bigger than in the original series, creating a blurred boundary between the limited diegetic universe of Twin Peaks and the real, pro-filmic world (one might also notice that the performers perform under their real names, not as “Roadhouse Singer” or other such fictional aliases, and The Bang Bang Bar, in this version of Twin Peaks, looks like Seattle’s real-life musical scene). The musical performances embody the combination of the old and the new in The Return, reminding the viewers of the place we want to return to, while pointing to a different sound and context. They are part of the diegesis, yet strangely unhinged and unconnected to the diegetic action. They are a part of Twin Peaks, yet somehow removed from it, and they are a marker of seriality within a ‘show’ that radically subverts our expectations of television storytelling and causality (fig. 27).

“The process is always the same,” as the editor Duwayne Dunham recently said to me, referring to his long-standing collaboration with David Lynch, “but it was special to re-enter Twin Peaks and see familiar places and faces. I was very surprised to see a mountain behind The R Diner. In the original, the weather was so bad I did not even know the mountain was there” (Halskov 2017c).

Indeed, Twin Peaks might be different things to different people, and there might be no real Twin Peaks, but only different understandings and perceptions of the town and the series. In that sense, the different stories about Twin Peaks (in the different tie-in books, the prequel, the original and the new series) give us different impressions of Twin Peaks, different perspectives, and that was exactly the idea.

When talking about his book, The Secret History of Twin Peaks (2016), Mark Frost told me that the creative process had changed this time, as he and David Lynch were devoted more exclusively to Twin Peaks, and the new series, he assured me, would combine elements from all of the different texts connected to Twin Peaks. “There’s a design to all of it, and it is ultimately all tied together,” as he said,

but we’re not going to spoon-feed anyone, wrapping it up nicely in a bottle. We are of course thinking about linking the different stories or texts, but you might learn that there isn’t one cohesive explanation. There may be no one thoroughly objective story. But the notion that it’s open-ended enough for people to draw their own conclusions is what fascinated me mostly, I think.

Halskov 2016b.

Art-TV and “moving paintings”: Twin Peaks in the post-network era

It’s wonderful to have this world again. And, yes, the vision is broader, deeper, and more compelling than before. I am only a small part of this story. But what it is to me is precious. I won’t kill the lark to discover its song and thereby lose both lark and song. All I’ll say is that I am so grateful to be on this ride again.

Wendy Robie (Nadine Hurley) (Halskov 2017e.

So far, the new Twin Peaks has had lackluster ratings in terms of flow-TV, but record-breaking numbers in terms of streaming on Showtime and sign-ups for Showtime’s streaming services (cf. Wilson 2017 and Wood 2017). The new Twin Peaks is not watercooler TV in the same way as the original series, but, then again, we are living in a post-network era where the television audience, like Dale Cooper, has been fragmented into multiple different segments (Lotz 2007: 4-5).

Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990-1991) was an anomaly when it came out, and it did not “change television (history),” as many tabloids claimed. It was described by Kristin Thompson as art-TV (a term that was also used to define the British genre-bender The Singing Detective [BBC, 1986]) and it was undoubtedly influential (cf. Thompson 2003 and Højer 2017). But the most experimental elements from the original series are still experimental when compared to modern series like Lost (ABC, 2004-2010), True Detective (HBO, 2014-2015), The Leftovers (HBO, 2014-) and Riverdale (The CW, 2017-), and the new Twin Peaks is even artsier and more abstract than its predecessor. Especially, the opening of Part 3 is abstract, and, as some fans have suggested, it might be a reference to Kenneth Grant’s book Beyond the Mauve Zone (1995). Just notice the colors. If that is the case, Cooper might be visiting ‘the mauve zone’ while being in a comatose state, and it would make sense for him to meet a character played by Phoebe Augustine (whose other character, Ronette Pulaski, awoke from a coma in the original series, cf. Reddit 2017) (fig. 28).

At the same time, though, the sequence in Part 3 seems to echo the opening of Eraserhead (1977), directly alluding to The Man in the Planet (Jack Fisk).

“Even when it aired on ABC, the original Twin Peaks pushed the boundaries of television and paved the way for many of the shows that we consider innovative storytelling even today,” as Carly Lane puts it. “Yet as dark as the first iteration of the TV series got, one got the impression that Lynch was never given free rein to depict everything he really wanted to.” And she continues: “These days, so-called ‘prestige’ television is moving the goalposts more and more when it comes to surrealism and the unsettling – two things David Lynch has always been a master of. Based on what’s been released so far this show is a perfect example of Lynch at his most Lynchian, whether we like it or not” (Lane 2017).

Sonia Saraiya of Variety was more ambivalent in her evaluation of the new series, pointing to David Lynch’s unique and unflinching vision as the series’ greatest and most frustrating quality. “The show is very stubbornly itself – not quite film and not quite TV,” she said. “Lynch’s vision is so total and absolute that he can get away with what wouldn’t be otherwise acceptable” (Saraiya 2017).

Twin Peaks: The Return is about returning, but it is also about coming back in a new incarnation, as if it were a zombie rising from the grave (as Laura Palmer says, “I’m dead, yet I live”), and it urges us to suspend disbelief and open our minds to the radical ‘otherness’ of the new Twin Peaks. It rejects habitualization and it refuses to appease us, but, profoundly abstract and non-linear as it is, it adds a new layer to our understanding of Twin Peaks.

That gum you like has, indeed, come back, but in a different style.

Facts

Note 1: The different interviews have been made in relation to a monograph about David Lynch’s films (The Art of Paradox), which will be published at the end of the year. We have consciously avoided going into specifics about the ‘new’ Twin Peaks (Showtime, 2017). We never discussed scenes or particular situations from the ‘new’ series, only Twin Peaks as a general phenomenon and David Lynch as an auteur.

Note 2: Thanks to Christian Hartleben for giving me inspiration regarding the chevron pattern in Twin Peaks, a pattern which is also seen on Leo Johnson’s sweater and on the blanket that Harold Smith uses to cover Donna Hayward (when she comes to visit him at his place).

Note 3: Adrian Martin has suggested that The Return might have been inspired by Jacques Rivette (particularly the jazzy, almost 13-hour long Out 1, noli me tangere [1971] which is also in parts).

Note 4: Thanks to Ingvar Hallström for providing me with further textual evidence for this reading. The article has been updated on June 24, 2017.

Bibliography

- Atad, Corey (2017), “Twin Peaks Is Back, But It’s Not Here To Appease You,” Esquire, May 22.

- BBC Arts (2014), “Patti Smith and David Lynch talk Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet and Pussy Riot,” November 14.

- Bickering Peaks (2017), “Bickering Peaks: A Twin Peaks Podcast – Facebook Update,” online: https://www.facebook.com/bickeringpeaks/?hc_ref=NEWSFEED.

- Bocko, Joel (2017), “Twin Peaks: The Return Part 3 – ‘Call for help,’ Lost in the Movies, May 22.

- Brandon, Jack (2017), ” ‘Twin Peaks’ Revival is Lynch unbound,” The Michigan Daily, May 31.

- Collins, Sean T. (2017), ” ‘Twin Peaks’ Recap: Keeping Up With the Joneses,” Rolling Stone, May 28.

- Davis, Ben (2017), “The Key to Understanding the New ‘Twin Peaks’ Lies in Another Dimension: David Lynch’s Art Career,” Art World, May 31.

- Frost, Mark (2016), The Secret History of Twin Peaks, Flatiron.

- Frost, Scott (1991), The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes, Pan Macmillan.

- Garner, Ross (2017), “What We Learned from Sam and Tracey: Does the New Twin Peaks Differ from Contemporary Quality TV,” CST, May 27.

- Halskov, Andreas (2015), “Between Two Worlds: The Competing Moods of David Lynch,” audiovisual essay, 16:9, April 19.

- Halskov, Andreas (2016a), “Interview with Peter Deming,” December 8.

- Halskov, Andreas (2016b), “Interview with Mark Frost,” December 13.

- Halskov, Andreas (2017a), “Interview with Chrysta Bell,” March 6.

- Halskov, Andreas (2017b), “Interview with Jonathan P. Shaw, May 23.

- Halskov, Andreas (2017c), “Interview with Duwayne Dunham,” May 27.

- Halskov, Andreas (2017d), “Interview with Ronald Eng,” May 29.

- Halskov, Andreas (2017e), “Interview with Wendy Robie,” May 30.

- Højer, Henrik (2017), “It’s not TV, it’s art-TV,” audiovisual essay, 16:9, February 21.

- Jensen, Jeff (2017a), “Twin Peaks: David Lynch Breaks Down the First Four Episodes,” Entertainment Weekly, May 26.

- Jensen, Jeff (2017b), “Twin Peaks Recap: The Return Parts 3-4,” Entertainment Weekly, May 28.

- Jerslev, Anne (2017), “Twin Peaks peaker,” Kommunikationsforum, May 24.

- Lane, Carly (2017), “How Twin Peaks’ New Non-Network Home Changes the Show and How We Watch It,” Nerdist, May 22.

- Lotz, Amanda D. (2007), The Television Will Be Revolutionized. New York: New York University

- Lynch, Jennifer (1990), The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer. Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster.

- Lynchland (2017): “David Lynch – Lynchland: Update,” admin. Roland Kermarec, June 2.

- Martin, Adrian & Cristina Álvarez López (2017), “Wrapped in Plasticity: Twin Peaks’ Myriad Laura Palmers,” audiovisual essay, Sight and Sound, May 12.

- Reddit (2017): [S3E3] The Mauve Zone Info.

- Rezayazdi, Soheil (2017): “Even Fire Walk With Me‘s Deleted Scenes Are Important to the New Twin Peaks,” Filmmaker Magazine, June 5.

- Rosenberg, Tal (2017): “Twin Peaks: The Return is a Bizarre and Brilliant Retrospective,” Chicago Reader, June 1.

- Rossi, Rosemary (2016): ” ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ to ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’: the Many Faces of Doug Jones,” The Wrap, December 2.

- Saraiya, Sonia (2017): “TV Review: David Lynch’s ‘Twin Peaks: The Return,” Variety, May 21.

- Shklovsky, Victor (originally 1917), “Art as Technique”, in Regent Critics, translated and edited by Lee T.

- Thompson, Kristin (2003), Storytelling in Film and Television. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, Leena (2017), “Twin Peaks Sets Showtime Streaming Debut Record,” Screen Rant, May 26.

- Wood, Matt (2017): “How Many People Actually Watched the Twin Peaks Premiere,” CinemaBlend, May 29.