|

|

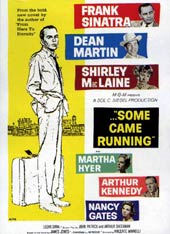

| Medium Shot Gestures However, I would prefer to step back from all of the lights and commotion of the fairground sequence and emphasize something else. Minnelli's reputation has often been that of a flamboyant metteur en scene, largely for his melodramatic set pieces and for his handling of elaborate musical numbers. But I believe that an equally strong case should be made for him as a major director for his staging of intimate scenes. This aspect of Minnelli's talent has not been entirely overlooked in the past. It is crucial to Barry Boys's essay on The Courtship of Eddie's Father (1963), published in Movie No. 10. James Naremore also discusses Minnelli's skill in this regard in The Films of Vincente Minnelli. But such an approach is also in danger of being forgotten or regarded as being, at best, a minor talent. Case in point: In a 1998 interview, Jacques Rivette makes the astounding declaration that Minnelli neglects the actor, citing Some Came Running as a film in which we find "three great actors" who are "working in a void, with no one watching them or listening to them from behind the camera" (Bonnaud). I must say that this runs contrary to any experience I have had in viewing the performances in Minnelli and I am certainly not alone in thinking that Martin gives the best performance of his career in Some Came Running. Whether Minnelli was simply fortunate in having so many gifted actors who were able to work around his own limitations or whether his method of directing with them was more complicated than has been assumed is a difficult issue to address within the scale of this paper (although my inclinations, as should be clear here, are with the latter). Rivette's attitude towards Minnelli (which is by no means an isolated one) is based on a fundamental misunderstanding. Discretion and RestraintIf Minnelli's work has consistently been misunderstood it may be that certain aspects of it point towards a certain type of behavioral, actor-based American cinema as epitomized by the work of someone like George Cukor. Some of Cukor's color and CinemaScope films of the 1950s, such as A Star is Born (1954) and Les Girls (1957) suggest a connection to the chic theatricality of some of Minnelli. But however visually detailed and beautiful these Cukor films are, he stages and frames his action in such a way that it is the actors who finally assume the primary focus of interest. Testimony from Cukor's actors confirms his attention to the most minute details of their performances. A number of actors who worked with Minnelli, on the other hand, have maintained that he devoted more attention to décor than he did to their performances. This attention to the visual which overwhelms the actor suggests a relationship to a cinema of the baroque-that of Welles, Max Ophuls, Josef von Sternberg-in which the actor, however central, is often absorbed into an ornate and strongly authorial visual style. But while an occasional sequence in Minnelli might allow for this kind of connection, his films never fully give themselves over to this impulse. Whatever visual vocabulary he may share with these three filmmakers, when measured against them Minnelli's own long takes and camera movements seem modest (in comparison with the first two filmmakers), his use of costuming and décor less extreme and fetishistic (in comparison with the two latter), his approach to matters of light, editing and sound not nearly as audacious (in comparison with all three of them). In the same passage from his autobiography in which Minnelli draws upon his well-known juke box analogy he also writes of his need to "temper" his enthusiasm when shooting Some Came Running, stressing the importance of "discretion" and "restraint" with material of this nature: "Part of the lore of the theater is to leave the audience wanting more, and this also holds true in films. Though you can do anything in films, you'd better not try." (Minnelli: 325-26) To contemporary sensibilities, this statement suggests a carefully manicured and well-behaved classicism, one which occasionally takes a stroll into the dark alleys of forbidden cinemas but only to quickly scramble back out to more respectable spaces. But this finally does not do justice to Some Came Running nor to Minnelli's particular talent, both of which are in need of careful attention. Formally, the Smitty's sequence is a very simple one: nine shots derived from six camera set-ups in a sequence running for four minutes. Camera movement here is slight from this master of camera movement and the use of color here is likewise understated from this master of color, consisting primarily of grays, blues, and browns. The "garishly lit primary colors" of the neon signs outside of Smitty's are muted here by daylight. One problem that arises in writing about this sequence, though, is that traditional shot-by-shot close analysis, however much it might produce important results for such figures as Hitchcock, Lang and Eisenstein, produces limited results for Minnelli. Indeed, for a director notorious for his fanatical attention to décor at the expense of the actor, what is often revealing about Minnelli's films is how uninteresting the individual shots are in freeze frame. What finally gives Minnelli's images their significance is how the actors are brought into these frames, how the actors move, speak, and gesture as part of a process of unfolding motion and dynamic interaction. It is not so much the shot that interests Minnelli as the frame. |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Distant Views |  Fig.1. | ||||||||||||||||||

Keeping the camera at this distance allows several things to take place. First, the three boys at the far right of the frame are constantly visible in the shot while other extras will walk in front of and behind Dave and Jane as they speak. Since both Dave and Jane remain in one spot in the center of the frame for most of this shot, the extras walking in front and in back of them provide a sense of movement within the frame. This attention to keeping the frame as alive as possible through minute attention to even the most minor of players suggests another link with the more extreme images of Welles, Sternberg and Ophuls. But where someone like Ophuls will use the extra in a more disruptive manner to the point where the extras actively compete with the leading players, Minnelli uses his extras as a kind of subtle extension of or counterpoint to the foreground action. Minnelli's refusal to more conventionally move his camera closer to Dave and Jane also allows Sinatra and Gilchrist to use most of their bodies as they speak. During this exchange, Sinatra mainly keeps his hands in his pockets (gesturing only to scratch his nose at Jane's mention of Dave's brother) while Gilchrist constantly gestures in a broad fashion, touching Sinatra, putting her hands to her face in an embarrassed gesture, shrugging her shoulders and using both hands to hold on to her shopping bag. As this transpires, the boys flipping coins at the far right of the frame assume a type of gestural counterpoint. Near the end of the sequence, another young boy (somewhat older than the other three) stealthily moves from around the outside right corner of the bar, passing through the three boys and then ducks into the front door. His gestures are based around the nervous smoking and eventual extinguishing of his cigarette just before entering the bar, setting up a contrast between the still somewhat juvenile behavior of the coin flipping from the younger boys with that of the smoking from the older one (fig.2). Dave follows him into the bar before first turning around and glancing at his watch. Everything in this shot is based on a subtle interplay of gesture and movement, framed within an extended medium long shot and modest camera moves which act as a type of theatrical frame. |  Fig.2. | ||||||||||||||||||

While not citing Minnelli's work, David Bordwell has drawn attention to the general decline in this type of complex ensemble staging in contemporary cinema (especially American). We are now living in a period of "intensified continuity," dominated by rapid cutting, free-ranging camera movements, and extensive use of close-ups. The nature of how performances are filmed, edited, and ultimately experienced has shifted: The face becomes the ultimate bearer of meaning, with gesture and bodily movements increasingly restricted through the alternation of "stand and deliver" scenes (in which the actors are confined to largely fixed positions) with "walk and talk" scenes (in which a moving camera rapidly follows actors as they "spit out exposition on the fly") (Bordwell: 25). While Bordwell does not note this, the shift in terms of how actors are filmed that he is describing has been part of an ongoing process over the last three decades, first sketched out by Manny Farber in his 1966 essay "The Decline of the Actor." Some Came Running, then, may be seen as a late example of this earlier cinema of relative gestural freedom. In comparison with contemporary approaches, Minnelli's handling of the actor in Some Came Running feels as though it has lumbered in from another era, pointing not only to the changes that have taken place over the last 45 years but also to how little influence this approach towards staging action has had on contemporary cinema. Theatrical Spaces | |||||||||||||||||||

Duel and Duet As in the first shot of the sequence, Sinatra's playing is marked by a paucity of gesture in contrast to Martin. But where a gifted character actress like Gilchrist works on a broad, emphatic scale, Martin's performance is one of relaxed casualness. While Sinatra seems to speak the lines directly as written, Martin repeatedly punctuates his line readings with hesitations and illustrates them with half-finished gestures (such as reaching for the ashtray in front of him as though to bring it forward but then only slightly adjusts it), giving an impression of spontaneity and improvisation. Sinatra's greatness as a popular singer far eclipses Martin's but Martin is a much more inventive screen performer, a fact which Sinatra implicitly acknowledges here by essentially giving the scene to Martin and not even bothering to compete. Martin looks at Sinatra almost non-stop while Sinatra mainly attempts to avoid direct eye contact. Near the end of the scene, Martin even seems to parody Sinatra's gesture of forcefully putting his glass down on the bar by immediately copying the gesture. If this scene may be thought of as a both a duet and a duel between two brilliant performers, it is Martin who ultimately wins, the final shot of the sequence belonging to him after Sinatra exits the frame. (The camera also comes closer to Martin in this scene than it does to anyone else when, in the sixth shot, he turns and responds to something that Dave says to Smitty in what might loosely be defined as a medium shot but one which also doubles as a type of close-up due to Minnelli's framing of Martin's face within the horizontal and vertical contours of the booth.) Martin's physical stature and style of dress also allow him to more fully dominate the space, his gray jacket, tie and pale pink shirt contrasted with the light brown of Dave's army uniform which seems to shrink Sinatra and which Sinatra accentuates by slightly pulling his body inward, presumably as a defensive measure against Martin. Both men are wearing hats, Dave's that of an Army uniform cap, Bama's a gray cowboy hat which far eclipses Dave's hat in stature. This icon of the Western genre, slightly urbanized for the film, allows for Some Came Running to be seen as a kind of Midwestern Western, complete with town saloon, the hooker with a heart of gold who is finally shot (Ginny), the prim schoolteacher (Martha Hyer's Gwen French) and our two male protagonists meeting at a bar, much of this playing like a bitter version of My Darling Clementine (1946). Bama's hat will continue to play a central role throughout the film since he refuses to take it off, even indoors, until the moving final shot when he performs his last gesture by removing it in memory of Ginny at her burial. Even before Bama is directly introduced, our first glimpse of him comes in the sequence's second shot, a panning movement across the interior space of the saloon as Dave enters. This movement not only plays a role as a conventional establishing shot it also initially presents Bama as a hat, a costume rather than a body, tucked away in the rear of the frame (fig.5). This idea of the body being literally engulfed by décor is one which recurs in Minnelli and Bama could almost be missed here on a first viewing. But Minnelli's composition also guides the viewer's eye to this back area of the shot, as the blue jeans on the boy trying to buy liquor off of Smitty at the right of the frame lead the spectator's eye to a matching blue line at the top of a poster on the back wall which, along with the white light hanging from the ceiling just above, leads the eye to the gray of Bama's hat. If actors sometimes complained that they felt as though they were little more than items of décor for Minnelli, what a shot like this one demonstrates is that these actors were not entirely wrong: Actor are often décor for Minnelli but only insofar as this décor will begin to move and assume a relationship to the body. |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Fig.5. | |||||||||||||||||||

Frank and Dean, Dave and Bama In Conclusion | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|