| |

16:9 in English: Neurosis Hotel

By ADRIAN MARTIN

The cinema of Abel Ferrara is in the tradition of John Cassavetes and Maurice Pialat: he seeks the truth of the moment, the nub of a contradiction, the telling flashpoint of tension. In interviews or documentaries, that is all he will talk about: ‘getting the shot’, nailing something in an image, a performance, an exchange, a riff. His cinema is a postmodern gestalt, a fusion in dissonance: bodies, environments, songs, colours and edits are so powerfully compacted in his work that we can hardly separate the elements, as we can with the work of ‘cleaner’ directors.

He who is not busy being born

Is busy dying

- Bob Dylan

The Evil Within

Is there any filmmaker more obsessed with death than Abel Ferrara? Not natural death, but murder: Ms .45 (1981), China Girl (1987), King of New York (1990), Bad Lieutenant (1992), Dangerous Game (aka Snake Eyes, 1993) and The Funeral (1996) all end with brutally final acts of killing - usually either by, or of, the central character (fig. 2). The Addiction (1995), like Ms .45 and Body Snatchers (1993), climaxes in an apocalyptic scene of mass slaughter (fig. 3). The Funeral begins with a mysterious death and proceeds to investigate it. Violent disappearances poke gaping holes in the structures of The Blackout (1997) and New Rose Hotel (1998). Lone, deranged serial killers drive his early work, from The Driller Killer (1979) to Fear City (1984), then the organised, corporate killers take over in King of New York, New Rose Hotel and ‘R Xmas (2001). In The Blackout we even go beyond death, into a particularly disquieting glimpse of the afterlife.

Some Ferrara films start with trauma, like the hideous rape in Ms .45. But what isn’t traumatic in the worlds conjured by this abrasive artist? Even walking out your front door - taking one step too many from the illusory comforts of home and family, as Harvey Keitel does in Bad Lieutenant and Dangerous Game - can register as a daily catastrophe, the beginning of a descent into hell. Obsession and addiction are the major themes of this oeuvre, the tripwires on which anti-heroes dance: could there be any plot premise more perfectly Ferraran than that of The Blackout, in which a reformed booze-drugs-sex addict comes to the insane (yet somehow workable) conclusion that the only way to penetrate the dark well of his past actions is to fall off the wagon and blackout all over again? These central characters are as fractured as the stories and forms that contain them: they move in a confused, psychic labyrinth of furious denials and compensatory projections. A sense of uber-Catholic ‘original sin’ looms large in Ferrara - a wound mainly endured by men in dim, instinctual recognition of the wrongs they inflict on their suffering, seething women.

But what, exactly, is the sin in Ferrara’s cinema - and where, exactly, is its origin? Is it just a personal matter of temptation, binging, deception, moral evasion - most of these men leading double lives as precarious and agonised as the archetypal ‘bad lieutenant’? Ferrara’s films offer a form of Brechtian melodrama beyond Douglas Sirk or even Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Every problem in his films is a social problem, a problem endemic to the formation and maintenance of a human community. Violence, exploitation, dissimulation: these are issues of the State, of corporatisation, technology, politics - inescapably.

Ferrara gives us such Big Picture problems in a heightened form, in stories frequently embracing the allegorical modes of science fiction, fantasy or horror: our world is populated with vampires, with vicious phantasms, with invading, marauding body snatchers. No wonder that an essay by the French critic Nicole Brenez (author of the best book on the filmmaker) is called “Abel Ferrara Versus The Twentieth Century”: for her as for Ferrara, the task is precisely to know, and to portray, what evil is in the modern world, and how it infects, inhabits, possesses us.

Angels of Vengeance

Ferrara developed his filmmaking skills during the 1970s via self-financed shorts, a crazy porn movie titled Nine Lives of a Wet Pussy (starring Ferrara!), and The Driller Killer, an edgy exploitation piece which rightly garnered a cult. Ms .45 is, however, the first major Ferrara film, giving full indication of his unique talent and sensibility. An entry in the ‘rape revenge’ cycle that includes I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Baise-moi (2000), Ms .45 details the oppression of mute Thana (Zoë Tamerlis) on every social level - sexually, at work, among her acquaintances.

The only way for a Ferraran hero or heroine to confront an insane, violent world is on its own terms, as a deranged vigilante. The result, in Ms .45, is a feminist film unafraid of courting the difficult contradictions in fantasies of guerilla empowerment. It sharpens the ambiguity common to rape-revenge tales: Thana doesn’t merely harden psychologically in the course of her payback quest (usually a sign of the vigilante’s loss of humane judgment, most recently in Neil Jordan’s The Brave One [2007]), she completely transforms, makes herself over - a spectacle that both distances and compels us as viewers.

Combining such confrontational exploitation content with a form worthy of Bresson (Thana’s psycho-acoustic world is eerily communicated), Ferrara builds to a devastating finale, set to an indelible jazz-disco counterpoint by his regular composer, Joe Delia. Ms .45 also inaugurated another key collaboration in Ferrara’s career: the extraordinary Tamerlis, later Zoë Lund (died 1999), who will later write Bad Lieutenant, and whose documentation of the New York drug scene clearly influenced ‘R Xmas. |

|

Fig. 1. Abel Ferrara.

Fig. 2. The bad lieutenant (Harvel Keitel) is killed at the end of the film.

Fig. 3. Mass slaughter towards the end of The Addiction (1995).

|

|

| |

Trash Compactor

Most great directors have signatures: Max Ophuls’ expansively tracking camera, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s static long shot-long takes, Jean-Luc Godard’s montage-mix of sampled and interrupted sound sources. But Ferrara? There is no consistent affectation, no recognisable manner in his prodigious forms. In the prolific ‘90s, especially, diversity rules: can it be the same director who mastered, so swiftly, the hyper-Michael Mann style of cool nocturnal blue in King of New York, the minimalist ‘stations of the cross’ intrigue in Bad Lieutenant, the stark black and white exploitation-horror of The Addiction, the stately, sombre mise en scène of The Funeral and the hallucinatory, multi-layered collage of The Blackout? (fig. 4)

This is one reason, among many, why it is so important to finally see these films as they were made to be seen - in prints projected onto a big screen through a loud sound system. Like Martin Scorsese, Leos Carax or Emir Kusturica, Ferrara makes ‘movie-movies’ that revel in the possibilities of cinematic sound and vision.

Yet if Ferrara lacks a signature - and maybe that, in our auteur-commodity market, slyly and subversively, is his signature - he has honed an attitude to content and an approach to form that are razor sharp. Ferrara is in the tradition of John Cassavetes and Maurice Pialat: he seeks the truth of the moment, the nub of a contradiction, the telling flashpoint of tension. In interviews or documentaries, that is all he will talk about: ‘getting the shot’, nailing something in an image, a performance, an exchange, a riff. His cinema is a postmodern gestalt, a fusion in dissonance: bodies, environments, songs, colours and edits are so powerfully compacted in his work that we can hardly separate the elements, as we can with the work of ‘cleaner’ directors.

It is this sensibility that led him to invent a mode, from his television work of the ‘80s (Miami Vice, Crime Story) to New Rose Hotel, of what we might call ‘canny distraction’: that seemingly random wandering of camera and microphone amidst a crowded mêlée of noises and events, an ambient, even ‘lounge’ cinema (after lounge music), “dilated and dedramatised” in Ted Colless’ description, where the focus seems always to be just approaching or just losing the centre of the action - but it’s that hazy, perpetually ‘becoming’ (and dying) totality which is precisely the Ferraran event, his ‘millennium mambo’. |

|

Fig. 4. Nocturnal blue in King of New York (1990). |

|

| |

Love is a Battlefield

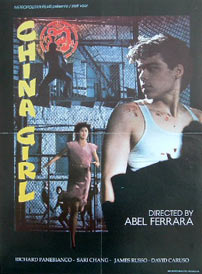

“The thing you can do in film is take physical objects and study them”, says Ferrara. In China Girl, Ferrara and cinematographer Bojan Bazelli took the trademark slick look of ‘80s film, TV and advertising - the look that turns every surface into a glazed design object or lifestyle accessory - and transform it into something wondrous, mobile, bottomless (fig. 5).

The entire movie - a modern star-crossed-lovers-in-the-hood melodrama, with respectful nodes to Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story - is hooked to an aesthetic ‘high’, whether representing scenes of love, violence, or gangland tensions (Little Italy versus Chinatown). Everything is a play of shadows approaching and receding, reflections in water still, shimmering or disturbed, struggles between light and dark forms and the metamorphoses between them - expertly cut to a soundtrack of beats, cries, provocations and counter-provocations. And it is all keyed to the stylised realms of music and dance, poised just before the point of becoming a full-blown musical (a genre that attracts Ferrara, as Go-Go Tales also gives evidence).

China Girl is unusual in the director’s oeuvre - albeit no less fatalistic - in its foregrounding of a romantic couple; henceforth, all such affairs will be dissolved into perverse triangles, daisy-chain encounters, and the ubiquitous monitoring of groups, families or communities. Already here, in Nicholas St. John’s script, the social collective is never far away: the eternal fight over territory allows Ferrara to make his first elaborated sketch of society as a prison, harshly geometric and devoted to the policing of personal lives and identities.

Black Holes

Like Stanley Kubrick’s stories, Ferrara’s narratives do not advance in the normal, conventional way - even when what they narrate is perfectly linear. Rather, they dwell, fascinated, on a particular plateau, a descriptive plane on which is etched an entire way of life, until a sudden turn lifts events to the next plot plateau. This leaves pockets of story or pieces of worlds, cast adrift as islands between large seas of ellipsis (especially in The Funeral where - as is often the case in Ferrara’s films - a radical edit takes out at the final phase of the work’s elaboration a lot of connective tissue). His characters cross these black holes only with the greatest difficulty, as if tearing themselves on glass with every fraught step, each mutilation marking a mutation of their being. |

|

Fig. 5. China Girl (1987). |

|

| |

This is an X-ray (and sometimes close to X-rated) cinema. Plots expose characters to a hellish gauntlet that renders them transparent - allowing us to see the complex networks of impulses and influences chaotically informing every little gesture. Ferrara’s images work this way also. They are like a skin which is progressively exposed, hollowed out, peeled back. His films often give us stark, cool, diagrammatic images, theorems of power and resistance (Ms .45, King of New York, The Addiction) (fig. 6). In the latter half of the ‘90s, a proliferation of different image formats or textures continues and deepens this exploration: TV, video, surveillance tapes, split-screens, digital treatments ... leading to an ambiguous cloud-cluster of image-types in collision in the montage. Watching The Blackout and New Rose Hotel, we can no longer tell whether we are seeing flashbacks, mental constructions, objective narration, or alternative, speculative worlds spinning off from the nominal fiction. And every time the ‘status’ of an image becomes ambiguous in this way we are back with questions of power and politics, of the ‘hidden hand’ behind image-circuits and image-systems, the hand of Mabuse-like figures like the director-manipulator played by Dennis Hopper in The Blackout …

Royal Road

Six masterpieces – King of New York, Bad Lieutenant, Body Snatchers, The Addiction, The Blackout, New Rose Hotel – with a couple of fascinating, highly accomplished, if somewhat programmatic works in-between (Dangerous Game and The Funeral). The lesser works of great directors, such as Garrel, are almost always programmatic, in two directions: they sum up, magisterially, everything that has gone before in the director’s career, and they throw out a line to the future, boldly experimenting with the introduction of a new element. From King of New York to New Rose Hotel: a compressed record of achievement, a royal road, to rival Preston Sturges 1940-1945, Godard 1960-1967, Luis Buñuel 1960-1978, or Clint Eastwood in recent years. How did Ferrara do it? |

|

Fig. 6. An image of power in King of New York (1990). |

|

| |

After his television work and several slight, rather impersonal features (particularly Cat Chaser, 1989), the kinetic, dazzling, flamboyantly violent King of New York took Ferrara to a new level of artistic achievement. The film gives the impression, at every moment, of reinventing the crime-gangster genre, and even the cinema itself. Ferrara and Nicholas St. John work engaging variations on given themes, characters and situations of the genre: the justification by the anti-hero of how benevolent acts of urban restoration justify building his empire on drug money; a scene with singer Freddy Jackson that effortlessly encapsulates the Godfather trilogy’s equation of show business, big business and criminal business; the assassin to end all assassins (Larry Fishburne as Jimmy Jump); brilliant action set-pieces in the rain, on a train, in a gridlock of cars; and gangster’s molls who, these days, double as crackshot bodyguards (fig. 7).

But this is far more than a genre exercise. Christopher Walken, immortal as Frank White, is almost David Bowie’s Thin White Duke: pale, wiry, opaque, as translucent at moments as celluloid itself, “back from the dead” to regain his empire (there is even a clip from Nosferatu placed in a Chinese mobster’s private cinematheque). Out of prison, White’s itinerary is only an ever-expanding series of cages: his base of operations, his beat, finally the vast city itself. White is a postmodern ‘Mr Big’ figure, fated to misrecognise the conditions of his own power - but at least Ferrara gives him a classic envoi: “I don’t need forever!”

Profane cinema

In Bad Lieutenant, A nun (Frankie Thorn), who has been brutally raped by a gang of street kids, kneels before a church altar in pious supplication. Beside her is LT, the bad lieutenant (Keitel) – bloated, shambling, incoherent, drugged out of his mind, unable to remain in the correct kneeling position, but nonetheless respectful enough of the faith to avoid saying ‘motherfucker’. They engage in a philosophical dialogue. LT promises her ‘real justice’: he vows to bypass the law and personally track down and kill her attackers. His rap is persuasive: wouldn’t this act prevent a repetition of such evil? But her response is firm: ‘I’ve already forgiven them.’ LT takes in the nun's Christian discourse, and offers this exasperated advice: “Get with the programme!” |

|

Fig. 7. An action set-piece in King of New York (1990). |

|

| |

It is a scene, like many in Bad Lieutenant, that teeters between psychodrama and hilarity, and which is impossible to place in terms of its reality-status. The two-shot forces together stark incommensurables: two ways of life (sacred and profane), two logics (ethereal and emotive), two acting styles (stiff and Method) (fig. 8). Is the nun really saying these things? Is LT perhaps imagining, projecting the whole thing from his tormented, guilt-ridden consciousness? We shall never know, because Ferrara’s direct, unadorned style equates the apparent reality of this story and its tawdry New York milieu with the inner visions (sordid and sublime) of its supreme anti-hero. After all, only a moment after the nun hands LT a set of rosary beads, he will turn to see (and likewise berate) Jesus Christ himself.

You will never find a narrative structure like this one advocated in a how-to-write-a-screenplay manual. The film tracks the decline of its anti-hero through a blur of scenes and sensations, with only the incessant drone of sports commentators on radio and TV casually marking the important stages of the plot. As viewers we are mercilessly plunged into the middle of every event, and rigorously denied any privileged or superior point of view. With Bad Lieutenant, Ferrara, like Pier Paolo Pasolini or Russ Meyer, fully chose the path of a profane cinema.

Mainstream Ferrara

In Body Snatchers, his most handsomely budgeted mainstream assignment (a true widescreen treat), Ferrara was unafraid to tackle the venerable property of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, previously filmed in 1956 (by Don Siegel) and 1978 (by Philip Kaufman). “Someone should do it every five years”, he remarked - so potent is the material’s peculiarly shape-shifting relevance to the crises of history. The script was worked over by many hands, including B-movie maestro Larry Cohen and Nicholas St. John, but the finished product ruthlessly boils down the central concept to its most horrifying social allegory: any institutional or ideological system that ‘gets inside’ you, which dehumanises the person but retains his/her superficial appearance, is in the business of body snatching.

And the terror starts, squarely, at home. This is a story less about the ‘monster as Other’ than about the social system itself as a monster. Ferrara takes on with evident glee the challenge of delivering a supernatural thriller. At the levels of image and sound, shock and suspense, plot and structure, this is among his most impressive works. It contains some of his greatest moments: from the scene of Meg Tilly’s haunting monologue (“Where you gonna run? Where you gonna hide? … Because there’s no one like you left”); to the most un-Hollywoodian climax of the initiation-quest for the teenage heroine (Gabrielle Anwar), her proud, all-too-human declaration over burning aliens: “I hate them”. In a time of fiercely renewed, global militarism, Body Snatchers rouses from its slumber to once more disturb us. |

|

Fig. 8. Philosophical dialogue in Bad Lieutenant (1992). |

|

| |

The philosophical horror movie

The Addiction is a return to such stylish, minimal, black and white horror movies as Carnival of Souls (Harvey Herk, 1962). Ferrara’s film assumes its fantastique premise (vampires prowling the streets) as an everyday mundanity - all the better to immerse itself in the mysterious moods and intensities of a cosmic post-trauma condition. The world is in a bad place here. Using a boldly didactic device characteristic of writer St. John, the NYU philosophy classes of Kathleen (Lily Taylor) index the 20th century’s grim inventory of disasters, wars, the Holocaust … And like for Thana in Ms .45, the burning question for Kathleen is: how to respond, what to do? (fig. 9)

Destiny - in the form of an encounter with a sexy lesbian vampire (Annabella Sciorra) - decides for Kathleen an undetached mode of engagement. Academic learning doesn’t stand a chance against the junkie-like lust for blood, and as the final slaughter explodes, The Addiction becomes, like Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day (2001), a genuinely philosophical horror movie. One of its themes is a reflection on performance: Ferrara’s films regularly redefine the parameters of screen acting and characterisation. Lili Taylor is the sum of her metamorphoses, a creature of drives, polymorphous perversity, pure screen presence (fig. 10). And Ferrara’s style accommodates such discontinuous acting with electric intensity: the spectacle of Kathleen hurling herself into a Bacchanalian dance or trying to claw a way out of her own body inspire enormous energy in the filming and cutting.

Ferrara and Hitchcock

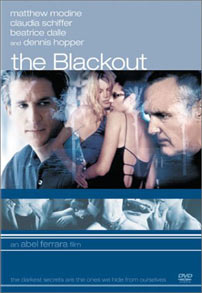

It is not uncommon to find The Blackout shelved among the erotica or even porn sections of large DVD shops (fig. 11). That rather helpless gesture indicates well the uncategorisable nature of Ferrara’s richest film, and the shadowy, outlaw existence that has accompanied it. Ferrara returns again, after Dangerous Game and before Mary (2005), to filmmaking as a subject. Matty (Matthew Modine) is a high-living celebrity who falls in with Mickey (Dennis Hopper), a conceptualist director modeled on the aged Nicholas Ray. Mickey is a man with a multiple video camera, an empty, labyrinthine club and an endless supply of real-life subjects for a psychodramatic ‘happening’.

In this vortex of images, sounds and fictions forever ‘under construction’, Matty will find and then lose his dark angel Annie (Beatrice Dalle) - and then find and lose her all over again in Annie 2 (Sarah Lossez), uncannily replaying, for our addled age, the plot of Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Meanwhile, in another time frame, Matty cleans up with his redemptive angel Susan (Claudia Schiffer) - thus cueing the famous Cassavetes crucible of ‘night life’ and ‘day life’ set into a dizzy, unstoppable, irreconcilable interchange.

Ferrara’s fractured telling of this tale is extraordinary: flashbacks, superimpositions, hallucinations, ellipses, all keyed to the rhythms, surges and undertows of a superb soundtrack collage featuring Ferrara’s favourite hip hop artist, Schoolly D. And what an ending: magical beyond David Lynch (because unexpected), bleak beyond the conclusion of Rossellini’s Paisa (1946), resonating immortally with its haunting, mysterious, final line: “Do you miss me?”

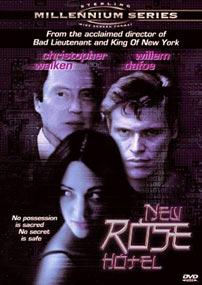

New Rose Hotel provides a kind of answer – a grand and mythic answer – to this beseeching question from an immortal, unknown, ever-fugitive woman (fig. 12). In the history of popular film, there is an intriguing, probably half-unconscious convergence between the figure of the femme fatale - the ‘bombshell’ who seduces for power - and the threat of nuclear war (Kiss Me Deadly [1955] is a classic example). Is this just our culture’s overactive misogyny, or is the connection more revealing? Laura Mulvey sees it as a modern repetition of the Pandora myth, triggering not only the negative associations of women with destructiveness, but more importantly the possibly liberating theme of female curiosity - the heroine as investigator and troublemaker in a man’s world.

Mulvey and Ferrara share a passion for the key film in this tradition, Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), of which New Rose Hotel is a particularly inspired and tortured remake. Once again, an operator in the criminal world (Willem Dafoe’s Fox) pushes his lover (Asia Argento’s Sandii) into an affair with a powerful man (Yoshitaka Amaro’s Hiroshi). Once again, a sinister, older figure (Christopher Walken’s ‘X’) pulls the strings. And once again our unlovely hero is wracked with projections arising from guilt and paranoia. But Sandii is a more provocative heroine than Ingrid Bergman, and her mysterious fate plunges New Rose Hotel into a vortex of poetic disintegration. This is a film that, midway, seems to break down and restart, splutteringly; what was previously merely enigmatic rapidly becomes cosmically inscrutable. Rarely has the auto-destruction of the cinematic apparatus been so thrilling as in New Rose Hotel. Alongside The Blackout, it is Ferrara’s most openly experimental work. |

|

Fig. 9. The Addiction (1995). Kathleen in class.

Fig. 10. Lili Taylor as a creature of drives at the end of The Addiction (1995).

Fig. 11. The Blackout (1997).

Fig. 12. New Rose Hotel (1998). |

|

| |

All in the Family

It might seem, from this brief look at his career, that Ferrara is obsessed with 'lone wolves', rebels who are far outside the social norm. But the theme of family has a special place in his work. He has explored the family unit in Bad Lieutenant, 'R Xmas and most deeply in The Funeral (fig. 13). Family means two things for Ferrara. On the one hand, it is the absolute symbol of difficult human togetherness or community, people locked into bonds and binds that they struggle violently to contest, transcend or affirm. On the other hand it is, equally, the absolute symbol which everything that Ferrara, as an intuitive anarchist, suspects and resents in society: order, rules, confinement, moral law, crushing and repressive relations.

It is fitting, then, that The Funeral (the last film, to date, scripted for Ferrara or for anyone by Nicholas St John, and a complete embodiment of this gifted writer's artistic sensibility) is a tortuous melodrama about a gangster family - a unit in which, ultimately, brother must kill brother.

With an astonishing cast that includes Vincent Gallo, Chris Penn and Christopher Walken (a last-minute replacement for Nicholas Cage), The Funeral is notable for three things: foregoing Ferrara's usual love of fractured montage, it is an experiment in long take mise en scène, doubtless inspired by the period setting; the narrative structure of flashbacks has a true meaning and force, beyond the back-and-forth games so typical of modern American independent cinema; and, finally, it is a remarkable attempt by Ferrara to deal with the subjectivity of women (played intensely by Isabella Rossellini, Gretchen Mol and Annabella Sciorra) and their fraught emotions when pinned hopelessly within a world of violent, doomed men.

Returning, six years later, to the theme of the family unit, ‘R Xmas is a more conventional, unusually non-violent film for Ferrara, employing a linear narrative and observational style heightened by constant, dreamy fades and superimpositions. But its recreation of the drug scene of the ‘90s has a remarkable, hypnotic authenticity. The family of ‘The Husband’ (Lillo Brancato) is both an ordinary, everyday brood and a functioning, criminal unit at the heart of an intricate, black market economy of drug manufacture and sales. Ferrara moves fluidly between these levels, slowly building an enigma which implicates the man in an ambiguous web of guilt and denial. |

|

Fig. 13. The family unit in The Funeral (1996). |

|

| |

‘R Xmas – announcing itself as the first in a series charting a ‘secret history’ of New York – builds fascination through the accumulation of intriguing detail, such as the painstaking preparation of drug bags. At its centre is the most extraordinary performance by a woman in Ferrara’s cinema to date, from Drea De Matteo as ‘The Wife’. Like the edgy, recent films of Paul Thomas Anderson or Spike Lee, ‘R Xmas builds an atmosphere of noirish dread from an obsessive concentration on the passages of daily life: walking down streets, entering doorways, running the gauntlet of a dark, clubland corridor or a lonely alleyway, - these become the Calvary-like stations of the Ferraran anti-hero, and those menaced souls dear to him (fig. 14).

Our Christmas

The Argentinean critic Quintín once charmingly proposed that there are two, diametrically opposed kinds of filmmakers affected by the legacy of Catholicism: Easter artists and Christmas artists. Easter artists are angst-ridden: everything to them is a question of masochistic crucifixion and desperately longed-for resurrection; death is their keynote, sin their crucible, redemption their dream. (Think Scorsese). Christmas artists are jollier types: they are more into a celebration of birth, of hope, of innocence, of new beginnings. (Think Capra.)

Where does Ferrara sit? All the evidence so far offered seems to point to the gloomy Easter camp. But let’s not forget that the ghostly splitting of identity, so prevalent in his films, leads us to at least one literal rebirth of a female hero, after the cataclysm in The Addiction. And then there was his comeback after several years of inactivity: ‘R Xmas, ‘our Christmas’.

But this more positive spirit truly surges forth in his two subsequent films, Mary and Go Go Tales (2007). Long nurtured as a project by Ferrara with various screenwriters, Mary at last reached the world as a furiously compressed film, a dazzling montage of ideas about how to live spiritually in a corrupt modern world. Sharing neither the morbid fixation on the Son of God’s physical suffering (The Passion of the Christ) nor the prurient speculation on Mary Magdalene’s sex life and ‘blood line’ (The Da Vinci Code), Mary compares three characters, each of whom represents a different way of experiencing and exploring religious belief: an actress (Juliette Binoche) who psychodramatically over-identifies with her role as Magdalene, dropping out of Western society and choosing to wander as a pilgrim in Jerusalem; a TV host (Forest Whitaker) who blindly blunders in bad faith in his personal life while he chairs on-air conversations with true-life religious experts; and a driven director (Matthew Modine as Ferrara’s alter ego) whose commitment to his own radical vision of the truth of Christ leads not only to his controversial film This Is My Blood, but also to a desperate course of action at the film’s picketed New York premiere.

All of these characters (as Brenez makes clear) are, in their own ways, visionaries: they set their fraught destinies according to the screen images they internalise, reject or create, and what appears to them in dreams or trances is no less real to them than the harsh events of the material world. Mary is a hallucinatory, provocative film ceaselessly torn between the spectre of global violence and the possibility of personal redemption. Its final moments – as in Dangerous Game, impossible to place within the linear continuum of either the flux of reality or the embedded fiction – mark a suspension of the apocalyptic, death-driven mode that has ruled so much of Ferrara’s career. |

|

Fig. 14. ‘R Xmas (2001). |

|

| |

Ferrara light

Go Go Tales will be forever known, in IMDb shorthand, as Ferrara’s first comedy – just as Chelsea on the Rocks (2008) will go down as his first documentary (albeit filled with ‘dramatic recreations’). And what a raucous, liberating film Go Go Tales is: a cascade of overlapping vignettes in a low-class bar (presided over by a manically inspired Willem Dafoe) that evokes all those performance-based films about the ‘end of an era’, from Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976/78) and Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion (2006) to Tsai’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). As in Mary, the American (New York) segments are mostly recreated in Italy, his production base at present; this literal displacement not only evokes Ferrara’s regrettably minor, almost excluded place in relation to the public annals of American Independent Cinema, but also creates remarkable effects of critical distance (fig. 15).

There is a strange mirroring between a moment in Go Go Tales – a film that remains largely unseen and ignored around the world – and the indie-style blockbuster that, on its releases, completely captivated the cinematic globe: Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007). In the Anderson, a bad, deceitful man (Daniel Day Lewis) stares at the very small child who we assume is his son; the scene cuts forcefully from the oil-covered black face of the man to the innocent, angelic face of the child. In the Ferrara, in the midst of Modine’s crazy musical act, his effete little dog looks at Asia Argento’s large, wild, unruly mutt. What is, for Anderson, the acme of a tortured Humanism – the entire weight of the social, moral world is held in that single overwrought cut – becomes, for Ferrara, a moment of lucid Surrealism, a militant dethroning of the sovereignty of the human principle.

In fact, the whole form and content of Go Go Tales tilts on a magnificent hinge: when the story abandons the official stage show (with all its attendant financial problems) and embarks on its ever-unpopular ‘amateur night’. This is the ‘switcheroo’ Cassavetes could not allow himself in the tragic vision of Chinese Bookie – although Ferrara may have taken his cue in this regard from another Cassavetes masterpiece, Opening Night (1977), when the fraught identity-play at last gives way to a clowning, non-narrative improvisation. Cinema sometimes gives us these miraculous moments of ‘letting go’, whose modern model is the shot of Isabelle Huppert suspending herself and swinging by one arm from a tree trunk in Godard’s Passion (1982): suddenly the plot dissolves, and every character shots away centrifugally from the centre (the literal movie set), walking, driving, floating, dancing … But, at the end, after the plot miracle of the finding of the lost lottery ticket, Ferrara’s worldly cynicism reasserts itself in one last, dark laugh: suspicion corrodes human-business relations, the tax department steps in …

However guardedly (Mary) or perversely (Go Go Tales), something nonetheless is stirring, responding to the light of life, in Ferrara’s latest cinema. From the burnout, the black hole, the infernal confusion and fire of our age, a new vision is emerging. We can only await the undoubtedly strange, vigorous, visceral, unpredictable wonders of Abel Ferrara Versus The Twenty-First Century. |

|

Fig. 15. Go Go Tales (2007). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|