| |

16:9 in English: Quiet Qualities and Qualified Quietude – the Sound Design of Gravity

By ANDREAS HALSKOV

The creative use of … relative or absolute silence is one of the unique characteristics of cinema – no other art form can achieve this...”

- Walter Murch (2003: 95).

Alien, the much-acclaimed sci-fi horror flick from 1979, has an evocative tagline which reads, ”In space no one can hear you scream” (fig. 1). The tagline for Scott’s film naturally helped build an ominous horror feel, thus assisting the viewer in understanding the basic genericity of the film. While generically defining the film and prompting the moviegoer to see the film, however, the tagline also had another – and much deeper – sense of truthfulness and gravitas. Thus, ominous as it sounds, the aforementioned tagline is simply true. In space no one would be able to hear you scream.

This presents an audiovisual paradox: How does one create an aural verisimilitude in a space film, if virtually no sound is heard in outer space? And to which degree should one strive for verisimilitude, when most people have never been to outer space, and instead harbor many (mis)conceptions of space from different simulated (and often highly inauthentic) films about outer space?

These questions are central to any film set in space – regardless of its generic DNA – and the short-hand answer could simply be: Do as Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or as Alfonso Cuarón in Gravity (2013) (cf. fig. 2-3).

This article focuses on the sound of Gravity, a sound design or sound score which in many ways is similar to that of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and which is spectacular and visceral, but in a way that clearly differs from the (other) sonic spectacles of the year.

The compilation score of American Hustle (2013; fig. 4), consisting of rock and pop hits from the 1970s, and the overload aesthetic of Ron Howard’s Rush (2013; fig. 5) are both typical examples of modern-day sonic spectacles.These and similar films flaunt their music and their sound work, and their scores have an in-your-face noticeability which is equivalent to David Bordwell’s concept of intensified continuity (which mainly refers to changes in terms of cutting, framing and lenses).

Following a brief introduction to modern-day sound theory, I shall listen more intently to the sound work in Gravity, focusing on the use of different channels as part of creating a visceral, at times even overwhelmingly claustrophobic experience. Also, and perhaps more importantly, I will focus on the use of ambient silence in Gravity – and how the use of quietude changes the experience and understanding of Cuarón’s film.

The Dolby Era – Modern-day Sound Cinema

In film sound theory, there is a general consensus that the use of sound – and the actual creation of sound designs – changed during the 1970s. According to Gianluca Sergi,

Hollywood’s use and conception of sound underwent a fundamental change. The possibilities of multi-channel technology, a wider frequency range and improved conditions of reproduction encouraged filmmakers to feel more confident about sound, and led them to rely more and more on the soundtrack. As a result, modern filmmakers have shown an increasing awareness of the ‘physical’, three-dimensional qualities of sound, and audiences are encouraged not just to listen to the sounds, but to ‘feel’ them – film goers experience sound more sensually than ever before. (Sergi 1998: 162).

From early sound films, which used only one soundtrack (whether magnetic or optical), and the use of three soundtracks in many classical Hollywood films, the use of multiple tracks became the norm in the 1970s, as seen in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979; fig. 6), whose impressive sound score is made up of 160 different tracks. This development of multi-track sound designs coincided with other technological changes, including Dolby’s A, B and C systems, and the creation of the actual concept of a sound designer (often connected to such technicians/artists as Walter Murch, Ben Burtt and Alan Slet). During the 1970s, then, a number of films were released that could naturally be used to promote and institutionalize the different Dolby systems. These included musicals (e.g. Grease [1978] and Hair [1979]), rock fantasies (e.g. Tommy and Lisztomania [1975]) and concert movies (e.g. The Last Waltz [1978]) (Chion 1994: 150-152).

What these films had in common – as opposed to earlier concert films and rockumentaries such as Monterrey Pop (1968) – was a density of sound and a layered use of multiple tracks. As director Michael Cimino puts it:

What Dolby does is to give you the ability to create a density of detail of sound – a richness so you can demolish the wall separating the viewer from the film. You can come close to demolishing the screen. (Cited in Schreger 1985: 351).

As a result of the different technological advances, many theoreticians and filmmakers argue that films from the 1980s and onwards have generally become denser, louder and more visceral. The Danish sound theoretician Birger Langkjær (2000: 139-164) talks of an overload aesthetic in many recent films, using Falling Down (1993) as a prime example; Michel Chion (1994: 154) talks of a superfield in today’s cinema, referring to the type of space created in modern-day multi-track films; Michael Allen (1998) speaks of a heightened realism in recent sound cinema; and Gianluca Sergi (2004) poignantly refers to this period in film history as the Dolby era.

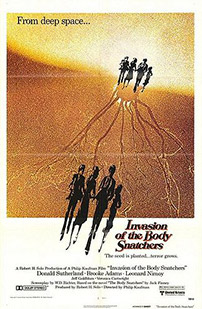

The different technological advances in the 1970s resulted in a number of rather gimmicky films, films such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978; fig. 7), Philip Kaufmann’s remake of the classical sci-fi movie, and Earthquake (1974; fig. 8), which used a rather intricate sound system called Sensurround in order to create a visceral experience of the disaster shown on screen. However, the technological advances in terms of sound also allowed for a much richer and explorative use of sound, and it ultimately paved the way for a type of film whose verisimilitude and physicality are as aural as they are visual. In the words of aforementioned composer and critic, Michel Chion,

… matter – glass, fire, metal, water, tar – resists, surges, lives, explodes in infinite variations, with an eloquence in which we can recognize the invigorating influence of sound on the overall vocabulary of modern-day film language […]. The sound of noises, for a long time relegated to the background like a troublesome relative in the attic, has therefore benefited from the recent improvements in definition brought by Dolby. Noises are reintroducing an acute feeling of the materiality of things and beings, and they herald a sensory cinema. (Chion 1994: 154).

The Subjectivity of Gravity

In accordance with Chion’s thoughts, one could naturally and plausibly say that the sound design of Cuarón’s film, using a multitude of different tracks, layers and channels – is as vital to the film’s aesthetic and the audience’s experience as is the visual side of the movie. Plotwise, Gravity is a relatively simple film about two astronauts, played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, who attempt to return to earth, but the experience of Cuarón’s ‘3D-Dolby spectacle’ is rich and visceral, and helpfully reminds the audience that films ought to be seen – and heard – in the cinema.

Dolby, who, according to their slogan, ‘elevate the entertainment experience’, has released a promo for Gravity, which actually takes the filmgoer through a step-by-step introduction to the sound work in Cuarón’s film (just as James Cameron’s film Avatar [2009] was released with technical promos flaunting the technicality and inventiveness of its 3D design) (cf. fig. 9).

In this promo (for Gravity), Cuarón, himself, tells us that for Gravity the use of sound has been important, particularly in terms of creating verisimilitude. “There is no sound in space,” as the director says, inasmuch as sound “cannot be transmitted through the atmosphere” (Dolby 2014). This point would naturally account for the noticeably quiet parts of Gravity’s sound design, but as Cuarón also explains:

Nevertheless, sound is transmitted through the interaction of elements, meaning that if our characters grab, touch stuff, the vibration of that will travel into their ears, and, so, they will get a muffled representation of that sound. (Ibid.)

The specific use of silence is a central element in Cuarón’s film, but what is equally interesting is the ubiquity of small noises and shifting types of music intentionally created for a surround sound system.

In a very concrete sense, this means that, whenever Clooney’s character, Matt, is stuck behind Dr. Ryan Stone (Bullock) – whether on or off screen – he is actually heard from a speaker placed behind the audience.

This, in accordance with the multi-layered use of Foley or transducer-recordings (of bolts being loosened, doors on the shuttle being opened etc.), make for a ubiquitous and often very confusing sound design which gives the audience (in the movie theatre) a subjective experience of being tossed about in space.

When Dr. Stone, for example, is suddenly set loose in space – on what could eventually lead to her ultimate demise – we hear, from the different speakers, different elements of low-rumbling music and sound effects that, because of her being tossed about, shift from speaker to speaker, thus mirroring Dr. Stone’s sense of disorientation. Following the different shots of Dr. Stone being thrown about in space, we get a number of extreme close-ups of Dr. Stone and some point of view shots where the sound design, apart from the sound of her breathing, is lowered to an almost claustrophobic quietude.

In cases like this, the sound design – particularly its use of silence or quietude – makes for a claustrophobic and subjective experience on the part of the viewer. However real or authentic it may be (given that there is no sound in space), the use of silence almost inevitably triggers a subjective reading of the scenes.

According to director Mike Figgis (2003: 1), there are two things you cannot do in a film: “one – never ever look into the lens directly; it’s almost like a biblical statement. ... And the other thing you can never do is have silence.”

In other words, the use of silence or silent sequences in a film is such a strong and noticeable effect that the audience would either think of it as a flaw or connect it with the psychological state of the character shown on screen. As I have written elsewhere, this sound effect is infrequent in films, and when used, it is often connected to a subjective experience, as in The Godfather Part III (1990), Lost Highway (1997), Bang Bang Orangutang (2005) and Babel (2006) (cf. Halskov 2008).

An Effective Interplay

The interplay of multi-track sound, silence and music, perhaps, is the most expressive and also impressive part of Cuarón’s film. Apart from the dialogue, created through ADR (Advanced Dialogue Replacement), the quiet passages and the surround quality of the shifting noises and music create a vivid sense of being stuck in a vast, yet also vacuous place – where, indeed, no one “can hear you scream”.

In the aforementioned scene, where Dr. Stone is thrown about in space, on the verge of being lost, we cut to a series of close-ups of her face, as she utters the words: “Huston, do you copy?” In these instances, however, the absence of diegetic sound (apart from her dialogue) together with the shifting but overly intense music creates a strong sense of not being heard. The dialogue is intentionally de-privileged, whereas the drone-like non-diegetic music seems overly intense (in comparison with traditional principles of sound design). This, however, is key to the experience of the scene, and the result is a highly subjective – at times even claustrophobic – experience.

Like the low-level, almost sub-audible rumblings in Irréversible (2002), the sound in Gravity, too, is central to the experience of the film going audience. Moviegoers had seizures, when faced with the sound design of Irréversible and Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009). After watching and hearing Gravity, this is perhaps hardly the case, but, in many ways, it is a spectacular and spectacularly sonic experience.

In traditional terms – at least according to Claudia Gorbman – sound and music in films should be “inaudible” or at least inconspicuous. Following the technological advances of the 1970s, that no longer is the case. Modern-day sound films flaunt their use of music (as in American Hustle, cf. the trailer), which could be used to create an authentic sense of time and increase the chances of cross-promotion (through the selling of soundtracks etc.) (cf. Smith 1998). Similarly, modern films, like Ron Howard’s racecar flick Rush (2013), flaunt their use of sound effects with an often densely layered use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound that naturally parallels the use of fast-paced editing, close-ups and bi-polar extremes of the lens-length (as Bordwell has pointed out).

The sound of Gravity is also spectacular, and, as the use of 3D, it can only be experienced to its full effect in the movie theatres. What is most striking about Gravity and its use of sound, however, is not its multi-track, multi-channel recording, but the way in which it uses a multi-channel system and long stretches of quietude to create a claustrophobic sense of being lost in space. We hear you, Dr. Stone… |

|

Fig. 1: The tagline for Alien (1979) reads like a headline for Alfonso Cuarón’s modern-day sound spectacle Gravity (2013).

Fig. 2-3: The silence in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Gravity (2013) could be realistically motivated, but in both films it has an almost claustrophobically subjective effect on the viewer.

Fig. 4-5: Modern-day films often flaunt their sound work in a way that totally disregards the classical principle of “inaudibility”. Frame pair: American Hustle (2013) and Rush (2013).

Fig. 6: The 160 sound tracks in Apocalypse Now (1979) paved the way for today’s densely layered and often complex, multi-track films.

Fig. 7-8: Two of many gimmicky sound films from the 1970s: Earthquake (1974) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978).

Fig. 9: Alfonso Cuarón talks about his richly layered multi-channel sound design in a Gravity promo, produced by Dolby.

Fig. 10-11.

Fig. 12-13. |

|