|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: Harry Horner’s Visual Design Program for Walter Hill’s The Driver

Af MARSHALL DEUTELBAUM

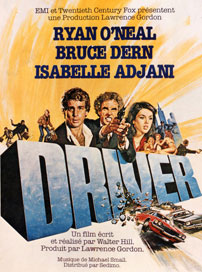

The Driver (fig. 1) is a terse, cat-and-mouse game in which a cop, known solely as “The Detective” (Bruce Dern), and a masterful getaway driver, known only as “The Driver” (Ryan O’Neal), take turns trying to outsmart one another. The film is so elemental that rather than having names, the characters are simply labeled by either their functions (e.g. “The Connection,” “Exchange Man”) or by some detail in their appearance (e.g., “Glasses,” “Teeth”). This essay examines how a similarly simplified visual style matches the narrative’s stripped down quality, while employing the play of red and blue to capture in colors the main characters’ struggle for dominance. An additional pleasure is the film’s self-conscious awareness of its cinematic roots in Los Angeles’ noir-rich Bunker Hill neighborhood.

The Driver and the Bunker Hill Neighborhood

Like the narrative, but almost twenty years earlier, a sizeable portion of the area east of Downtown Los Angeles where the film would be shot had been stripped to bare earth for an urban renewal project known as “The Bunker Hill Redevelopment Project,” designed to replace a lower middle class neighborhood with skyscrapers whose skyline would assert Los Angeles’ status as a world class city.

However, apart from the John Portman-designed Westin Bonaventure Hotel which opened shortly before principle photography began (and which appears briefly in the film), little of the area had been rebuilt in the two decades since it had been cleared (1).

The Driver is rich in allusions to earlier films noir set in the no longer extant neighborhood of Bunker Hill. In the 1940s and 1950s this run-down neighborhood, bounded by 1st Street and 5th Street on the north and south, and Figueroa Street and Hill Street on the east and west, had been the location for such films noir as This Gun for Hire (1942), T-Men (1947), Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948), Criss Cross (1949), Cry Danger (1951), M (1951), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), The Exiles (1961), and Angel’s Flight (1965), as well as nearby Union Station (1950) which remained untouched by urban renewal. Mike Davis addresses the connections between some of these films and the area in “Bunker Hill and Hollywood’s Dark Shadow,” while L. A. Noir: the City as Character (2005) contrasts recent photographs of the area with production stills from films shot in and around Bunker Hill, including The Driver, that further illustrate how thoroughly “The Bunker Hill Redevelopment Project” denuded the area over the course of those years.

Shooting the film’s chase sequences at night hid the leveled topography of Bunker Hill in darkness. All that remains to identify the area to knowledgeable viewers are the large street signs legible at intersections as the cars race by them. Seen from this perspective, Walter Hill’s decision to shoot The Driver in this area, despite its being stripped of most of its buildings, suggests how well-aware he must have been of what Bunker Hill had meant to filmmakers. In addition to this awareness of the significance of place, Hill’s script demonstrates his desire to locate The Driver in the cinematic lineage of film noir.

The Driver, Le Samouraï, and This Gun for Hire

The film’s taciturn, eponymous main character, The Driver, is a direct descendant of Jef Costello, the taciturn main character of Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), whom Melville claimed to have modeled, in turn, after Raven, the similarly taciturn killer played by Alan Ladd in This Gun for Hire, a film that transpires, as does much of The Driver, in and around Union Station.

Hill begins The Driver with an hommage partially recreating the opening of Le Samouraï. Melville’s film begins with Jef Costello’s theft of a car, his elaborate preparations for the alibi he knows he will need in a few hours, and his visit to “Martey’s,” a nightclub, whose owner he kills in the club’s back office. As Jef leaves the office after killing the owner, he comes face-to-face in the narrow hallway with Valérie, the club’s piano player. The two exchange a lingering glance before Jef pushes his way past her. As he expected, Jef is picked up in a police dragnet a few hours later and put in a line-up arranged for the witnesses from the club to view. Even though she got a good look at Jef, for reasons of her own, Valérie claims not to recognize anyone in the lineup as the person she saw leaving Martey’s office.

Hill recreates these events as an ineptly executed robbery instead of a murder. The Driver, an expert at handling a getaway car, not a killer for hire, like Costello, steals a car and arrives at a pre-arranged time in the parking lot of a poker parlor. As she was hired to do, a woman known in the film only as The Player distracts a security guard’s attention to set the theft in motion. However because the robbers take longer than planned, The Driver is forced to linger with his car idling in plain view of patrons entering and leaving the club. In addition, the robbers’ delay enables the police responding to the robbery to arrive just as the thieves begin their getaway. After a lengthy car chase that amply demonstrates why he has the reputation of being the best wheelman in the business, The Driver manages to elude the police. Paralleling what happens in Le Samuraï, the police eventually pick up The Driver to see whether any witnesses can positively identify him as the man at the wheel of the getaway car. But just as Valérie claimed to be unable to recognize Jef in Le Samouraï’s line up, The Player tells the police that she is certain that The Driver is not the man she saw driving the getaway car.

The Driver’s Stripped Down Visual Style

While Walter Hill’s script places the film squarely in the film noir tradition, the job of making The Driver visually cohesive fell to Harry Horner, the film’s production designer. The recipient of two Academy Awards for the set designs of The Heiress (1949) and The Hustler (1961), Horner had done the set design for one film noir, A Double Life (1947), and had directed two noirs himself, Beware, My Lovely (1952) and Vicki (1953).

Shooting most of the film at night hid the leveled topography of Bunker Hill in darkness. (The little daytime filming was shot in the city’s adjacent financial district.) Shooting on location, however, meant that pre-existing structures offered little, or, in the case of scenes filmed in Union Station, no possibility of any substantial reworking. Horner had to work with what was already there. He solved the problem by designing the film to be as visually stripped down as circumstances permitted.

A design program translates a film’s dramatic concerns into visual terms. A realistic film shot largely on location like The Driver required the use of visual elements that might be found plausibly within everyday reality. Thus even though a design program is unavoidably symbolic to some degree, its symbolism is subtle, seeming to arise ‘naturally’ from the depicted reality. Horner solved the design challenges posed by shooting The Driver on location through a series of related decisions in which the narrative’s stripped down qualities are mirrored by simplified sets and costumes, while the central dramatic conflict of the main characters is captured by a conflict of colors. |

|

Fig. 1: A French poster for The Driver (EMI Films / Twentieth Century Fox Films, 1978; written and directed by Walter Hill). Harry Horner was production designer on the film. Philip Lathrop was director of photography. While Lathrop and Hill surely knew of the design program for the film, the choices discussed here primarily relate to the production design of Harry Horner.

(1) For a discussion of the changes to the area, see Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Gail Sansbury (1995). An essay with a model of Bunker Hill and images of the changes that occurred during urban renewal can be found here. A current map and guide to the area can be found here. |

|

| |

The film’s stripped down visual program is epitomized by sets with broad expanses of monochromatic color largely free of decoration. Horner controlled the appearance of many pre-existing settings by removing from them the visual clutter of everyday reality. Several sequences, for example, take place in parking garages devoid of cars. All that remains of them, visually, is the monochromatic gray of recently poured concrete or its rustier, decayed version (figs. 2-3).

The Westin Bonaventure Hotel is filmed in a similarly minimal fashion when The Driver meets The Player there to pay her off. The sequence takes places at night on a walkway to the hotel that is lit at either side at ground level solely by bands of fluorescent lights set in the base of the low concrete walls running the length of the walkway. As filmed, the scene looks almost abstract: the two characters dressed in black, silhouetted against some undecorated, monochromatic portion of the hotel’s exterior and flanked by the walkway’s monochromatic concrete border as it diminishes in perspective (fig. 4). ] In contrast to the darkness of the exterior sequence, the hotel suite that serves as The Player’s apartment is largely white. The white walls and geometrically simple décor continue the simplified, virtually unadorned style of the hotel’s exterior (fig. 5).

A similar chromatic simplification marks the combination of ochre and browns in The Driver’s undecorated apartment, while the long hallway leading to it is entirely ochre (figs. 6-7). Likewise, the film’s wardrobe, one area that Horner could control most of the time, is limited to solid colored clothing in a narrow range of blues, grays, browns, and black--except, as I explain below, during a key sequence in Union Station.

All in all, then, despite location shooting Horner manages to produce a visually simplified Los Angeles that never seems, at least while a viewer experiences it, to be artificially manipulated. This is as it should be, for as Horner once explained his design process:

I construct the design for a scene from the story. So the architecture, its spatial qualities and its contents are not designed to be recognized as symbols. If symbols are used, they are hidden, and cannot be understood, nor function without the performance. (Gambill 1983, p. 227.)

Conflicting Colors Mirror the Characters’ Dramatic Conflict

While the design program I have described thus far visually echoes the sparse, stripped down feel of the narrative, it is only the background against which the play of paired red and blue colors are used to echo the narrative’s driving force, the cat-and-mouse game between The Detective and The Driver.

The Detective explicitly describes the job of chasing criminals to his associates as a game: “You know the best part of our job is? It’s just a game. It’s either them or us.” Later, after setting his trap, The Detective visits The Driver at his apartment to entice him into risking capture by agreeing to play what he calls “a game:”

The Detective: I really like chasing you.

The Driver: Sounds like you got a problem.

The Detective: Oh-ho. I’m much better at this game than you are. You play against me, pal, you’re gonna lose. You win, you make some money. I win, you’re gonna do 15 years. How about it Driver?

At the film’s end, neither man has won or lost; the bank heist arranged by the Detective in hopes of catching the Driver with the stolen loot goes awry and, to everyone’s surprise, someone else makes off with the money. But far from being a frustration, the concluding stalemate means that the game which binds the men to one another can continue a while longer. The game itself, not the final outcome, is what is most important.

Throughout the film Horner juxtaposes the play of red and blue as a visual analogue, or correlative, for how the two men are bound together in their cat-and-mouse game. Because convention holds that the color red is “hot,” like the quick tempered Detective, while the color blue is “cold,” like the emotionally controlled Driver, one might say that the colors, like the characters, are symbolic opposites. However, the opposition of these colors is also physiologically apt for optically the colors “pull” in opposite directions. As Edward Branigan explains,

The opposition of red and blue is often stated in spatial terms: reds advance toward the viewer, blues recede. This effect finds support in the well-known spatial cue of aerial perspective (the blueness of distance) and the fact that the lens of the eye is subject to chromatic aberration, which means that red light is focused behind the retina (as in far-sightedness) and blue light in front of the retina. Thus the tension engendered by red and blue appearing together begins as an optical stress in the musculature of the eye as the lense alternately tries to focus first one, then the other color. (Branigan 2006, pp. 174-175.) |

|

Figs. 2-3: Monochromatic parking garages devoid of vehicles typify The Driver’s stripped-down design program.

Fig. 4: The stark geometry and bare surfaces of The Westin Bonaventure Hotel further illustrate the design program.

Fig. 5: The Player’s apartment is consonant with the film’s stark design program.

Figs. 6-7: The undecorated surfaces and simplified color-scheme continue in The Driver’s apartment and hallway. |

|

| |

The pairing of colors begins when the film begins: The Driver chooses a car to hot wire for a job, a blue Ford parked next to a red BMW (fig. 8). Similarly, the film’s first image of The Detective presents him flanked by people dressed in red and blue as he lines up a pool shot. In addition, parallel red and blue neon tubes running the length of the wall behind the bar are visible in the background (fig. 9). The bound relationship of red and blue in the film is most perfectly realized by the alternating red and blue lights on the rooftop light bars of the police cars pursuing The Driver after the robbery. It is their alternating quality, the shift from one color to the other, that captures the shifting relationship of The Driver and The Detective as each tries to outsmart the other (fig. 10). And to underline that neither color is inherently dominant, The Driver begins by driving a blue Ford, but ends the film by driving a red pick-up truck. As if to further emphasize that it is the relationship between the colors that is important, not either color by itself, the fence visible in the background when The Driver switches vehicles have been daubed with red and blue splotches (fig. 11).

Fig. 11: Midway through the film, The Driver switches to a red pickup truck. The red and blue splotches daubed on the fence in the background continue the pairing of the colors.

Costuming continues the design program when The Driver puts a satchel of stolen money into a locker at Union Station. The pre-existing, predominantly yellow décor of Union Station’s interior couldn’t be modified to fit the design program, so extras dressed in blue and red appear prominently among the crowd, conveniently blocking a clear view of the Station’s interior. The movements of these extras are carefully choreographed to keep red and blue visible within the frame. Thus when The Driver arrives at the bank of lockers in Station’s lobby, a couple, the man dressed in a blue jumpsuit and the woman in a blue and red sweater and blue slacks, open a locker in the background and put a blue bag into it. While they are doing this, a redcap dressed in a red jacket and cap pushes a cartload of baggage from the background toward the camera. Just as he approaches the camera and is about to move out of view at the left side of the frame, a woman dressed in a blue jumper and red, floral-patterned sweater appears from behind the other side of the camera walking toward the background (figs. 12-13). For an instant as The Driver closes the locker’s door, he and all these extras are simultaneously visible. Elsewhere, props serve the same purpose as costumes. Thus during a chase later in the film, a stack of appropriately blue barrels are sent flying as The Driver in the red pickup truck pursues a red and blue Chevy Camaro (fig. 14).

Fig. 14. A red and blue Camaro pursued by The Driver in a red pickup truck bursts through a stack of blue barrels. |

|

Fig. 8: At the beginning of the film, The Driver steals a blue Ford for his getaway car rather than the red BMW parked beside it.

Fig. 9: Bracketed by men red and blue clothing, The Detective is introduced shooting pool in a bar decorated by red and blue neon.

Fig. 10: The pairing of red and blue continues in the alternating lights atop the pursuing police car.

Figs. 12-13: Extras dressed in blue and red are choreographed to fill the frame in this key scene in Union Station. |

|

| |

At times, Horner finds red and blue already paired together in pre-existing reality. The film’s final chase aboard an Amtrak passenger train in which The Detective tries to get the best of The Driver takes advantage of the pre-existing pairing of red and blue in the branding of Amtrak, America’s national railroad passenger system, to keep the design program foregrounded. The sequence begins with a shot that traces how the wide red and blue bands painted next to each other on the nose of the locomotive continue on the locomotive’s side as well as on the sides of the passenger cars behind it. The interiors of the passenger cars incorporate the same red and blue in the seat upholstery and route map on a bulkhead (figs. 15-16). And as if to insist that the pairing of these colors is significant even though what has been shown thus far occurs in pre-existing reality, there is a shot of red and blue travel bags in an overhead rack seemingly placed beside one another by chance, but nevertheless reminiscent of the red BMW and blue Ford parked beside one another during the film’s opening sequence (fig. 17).

This tracing out of the film’s color program demonstrates that far from being a matter of chance, the simplified set designs of The Driver, along with the continuing play of red and blue, articulate the limited options of a fated neo-noir world every bit as effectively as the chiaroscuro of black and white cinematography often mirrored the circumscribed possibilities of the films shot in and around Bunker Hill during the classic noir decades.

Increasingly filled-in in recent years with such upscale projects as the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and a variety of expensive condos, re-vitalized Bunker Hill no longer belongs in a depiction of a noir world. To catch a glimpse of Bunker Hill as it used to be, one has to search the edge of the area, as happened when L. A. Confidential (1997) found a location on Fifth Street to serve as the Nite Owl coffee shop. Otherwise Bunker Hill now has to be recreated in a studio, as was done in South Africa for the filming of Ask the Dust (2006).

The reputation of The Driver has languished since its release, though the similarity of Ryan Gosling’s portrayal of the nameless, taciturn wheelman in Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011) to Ryan O’Neal’s performance in The Driver has renewed interest Hill’s film (2).

The old Bunker Hill is long gone, but the geneology of Drive can be traced directly back to it by way of The Driver. |

|

Figs. 15-16: The red and blue nose of an Amtrak locomotive, along with the train’s interior décor of the same colors, become the site of The Driver’s and The Detective’s conflict.

Fig. 17: A brief shot of red and blue travel bags beside one another in an overhead rack signals the constructed nature of the colors’ continued pairing.

(2) Jaime N. Christley suggests that Refn was influenced by The Driver. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

Literature

Branigan, Edward. “The Articulation of Color in a Filmic System: Deux

ou trois choses que je sais d’elle.” In Color: The Film Reader. Ed. Angela Dalle Vache and Brian Price. New York and London: Routledge, 2006: 170-182.

Christley, Jaime N. ”Drive.”

Davis, Mike. “Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow.” In Cinema and the City: Film and Urban Societies in a Global Context. Ed.

Mark Shiel and Tony Fitzmaurice. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2001: 33-45.

Dimenberg, Edward. “From Berlin to Bunker Hill: Urban Space, Late Modernity, and Film Noir in Fritz Lang's and Joseph Losey's M.” Wide Angle 19.4 (1997): 62-93.

The Driver. Region 1 DVD. Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2005.

Gambill, Norman. “Harry Horner’s Design Program for The Heiress.” Art Journal 43.3 (1983): 223-230.

Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia, and Gail Sansbury. “Lost Streets of Bunker Hill.” California History 74.4 (1995): 394-407, 448-449.

Silver, Alain, and James Ursini. L. A. Noir: The City as Character. Santa Monica, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2005.

Please put down the information for the Facts box here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - september 2012 - 10. årgang - nummer 47

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-12. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|