|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: The Biography of Great Men – The Political Biopic in America

By ANDREAS HALSKOV

A genre firmly rooted in the genre system of Hollywood, the biopic is not only alive today, but ‘alive and kicking’. Films like Phyllida Lloyd’s The Irony Lady (2011), starring Meryl Streep, Simon Curtis’ My Week with Marilyn (2011) and Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar (2011) all attest to the popularity of the biographical film. A subgenre of the biopic is the political biopic, a subgenre which has often been neglected in Denmark, but which has always been a stronghold in the US. In this article, I shall give a brief historical overview of this subgenre in American cinema, explaining how its success is related not only to Hollywood’s star system, but also to a personalized political history often connected to the US.

The Scottish historian, critic and author Thomas Carlyle (fig. 4) has famously said that ”The history of the world is but the biography of great men,” pointing to a personalized conception of history which has often been debated and largely disavowed.

This particular view, however, is suitable when trying to explain the success of the political biopic in the US, where presidents are often the stuff that tales and films are based on. The so-called “founding fathers”, with whom most Americans are acquainted, have been fictionalized in the biographical miniseries American Lives (PBS, 1997) and HBO’s John Adams (2008), starring Paul Giamatti; Abraham Lincoln has been depicted many times over, most popularly in the eponymous film by D.W. Griffith (1930) and John Ford’s The Young Mr. Lincoln (1939); Franklin Delano Roosevelt is central to a miniseries from 1965, starring Charlton Heston; Harry S. Truman is played by Gary Sinise in the telefilm Truman (HBO, 1995); John F. Kennedy’s tragically short life has often been investigated and depicted, most recently in the miniseries The Kennedys (History Channel, 2011-) in which he is played by Greg Kinnear; Richard Nixon is the ‘tragic hero’ or ‘crook’ in Oliver Stone’s film from 1996 and part of Ron Howard’s critically acclaimed film Frost/Nixon (2008); Ronald Reagan is played by James Brolin in The Reagans (CBS, 2003) and George W. Bush has recently been played by James’ son Josh Brolin in the slightly satirical film W (2008) by aforementioned Oliver Stone.

Focusing specifically on the two Lincoln films (Griffith 1930 and Ford 1939) and the two films on Nixon (Stone 1996 and Howard 2008), I shall try to describe the typical features in political biopics and, at the same time, explain why this particular subgenre is so popular in America, yet almost unnoticeable in Denmark (1).

Fig. 5-7: The political biopic has a long-running tradition in America and includes well-known films like W (2008), Nixon (1996) and The Young Mr. Lincoln (1939).

The Political Biopic

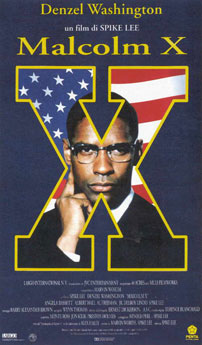

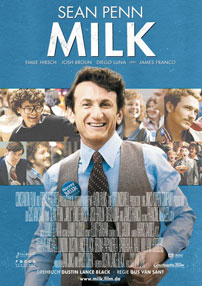

A rather vague and often neglected genre, the biopic may generally be construed as a ‘genre depicting the life of a famous person in an often dramatic form’ (Schepelern 2010, p. 81; see also Nielsen 2011). This genre, thus, includes a variety of different films: from musical biopics (films like Ray [2004] or Walk the Line [2005]) to philosophical biopics (films dealing with major thinkers such as Voltaire [1933]) and, as mentioned, political biopics,dealing with people who have (had) a great influence on political events and the political system (from fictionalized accounts of presidential lives to films like Malcolm X [1992] or Milk [2008], about the gay activist Harvey Milk, played by Sean Penn (fig. 8-9)).

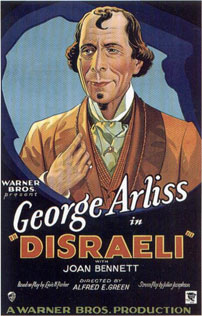

We may naturally assume that this genre (as most of Hollywood’s classical genres) harks back to the infancy, if not the very birth, of cinema. Even so, says Rick Altman, early biopics like Warner Bros.’ Disraeli (1929) (fig. 10) were not originally produced and advertised as biopics (Altman 2002, p. 39). “Films are always available for redefinition […] and genres for realignment,” writes Altman, and, thusly, political biopics may have existed for many decades, but the term itself – political biopic – is relatively new and only vaguely defined (cf. Altman 2002, p. 42-44).

That political biopics are only vaguely defined is hardly a surprise, given the fact that the biopic is actually a rather vague genre with only a few, if any, necessary stylistic features. Trying more specifically to define the political biopic, however, we could point to a number of features which are often, but not necessarily, seen in such films, including |

|

Fig. 1-3: ”The return of the real”: Biopics are flooding the market these days, and within the last four years political biopics have been made on such diverse political figures as John Adams (HBO, 2008), Margaret Thatcher (The Iron Lady, 2011) and J. Edgar Hoover (J. Edgar,2011).

1) Granted, there are films in Denmark – even if they are few are far between – which can be seen as political biopics. The film AFR (2007) could in a sense be construed as a biopic about Anders Fogh Rasmussen, former Prime Minister of Denmark, but is more accurately described as a mockumentary. En kongelig affære (2012, A Royal Affair) by Nikolaj Arcel, however, is a biopic about Christian VII, a former Danish king, but also about J.F. Struensee as a somewhat dubious politician.

Jens Otto Kragh, the most obvious choice for a political biopic in Denmark, is seen (although not as a central character) in the drama series Krøniken (DR, 2004-2007), and both a political biography and a biographical stage play have been made about his life (as a politician and a private person).

Fig. 8-9: Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992), about the eponymous civil rights leader, and Gus Van Sant’s Milk (2008), about a lesser known political activist, could both be considered political biopics. This subgenre, in other words, can focus on virtually any kind of political figure who has (had) an influence on the political system.

Fig. 10: George Arliss stars as the former British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli in the 1929 Warner Bros. film Disraeli, which is known today as an early political biopic. The film, however, was never produced and sold using that nomenclature.

|

|

| |

- An actor playing a central political figure, whose life is depicted and dramatized;

- An emphasis on tour de force acting, particularly the physical and psychological characteristics of the portrayed politician, e.g. in relation to facial and bodily appearance, verbal dexterity, gesticulations and mimicry (2);

- A fictionalized account of authentic historical events;

- A dual focus on the political figure as a public and private character;

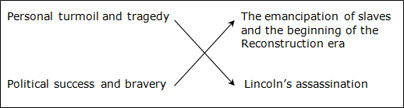

- A success <-> tragedy structure, often juxtaposing a private tragedy (e.g. the assassination of Lincoln) and a political success (e.g. the emancipation of the slaves), or vice versa;

- A use of authenticity-enhancing features such as captions (as a temporal and spatial marker) and archival footage.

The Political Biopic and the Star System

It is a well-known fact that American films are streamlined and systematized, and that Hollywood is known for its industrial, conventional way of creating films. “A successful product is bound up in convention,” writes Thomas Schatz, “because its success inspires repetition.” (Schatz 1980, p. 5). Accordingly, American films abide by different systems, i.e. the genre system (based on readily recognizable genres), the studio system (where the production, distribution and exhibition of films are centralized and controlled by a few major companies), the continuity system (where films are edited in a seamless way, allowing for identification and immersion) and the star system (where films are sold through reference to major stars like Marlon Brando and Meryl Streep, for whom the films become vehicles, re-affirming their stardom) (ibid.).

In this particular context the biopic is particularly interesting, since films of this genre are not only readily recognizable, but also natural vehicles for great actors and actresses. A biopic, in other words, is “Oscar material”, inasmuch as the film relies heavily on an actor’s ability to imitate or mimic a famous person. |

|

2) In the wording of this particular passage I am indebted to Jakob Isak Nielsen, who has edited this article. |

|

| |

Most of us, it seems, have a natural interest in imitation, and impersonations have long been a popular attraction – from various Elvis impersonators to stand-up comedians (e.g. Jim Carrey) humorously mocking celebrities (such as Clint Eastwood) and actors playing well-known people, thus propelling their careers to new heights of stardom.

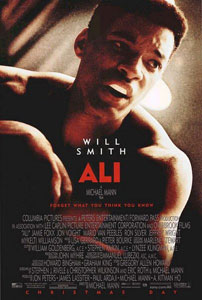

Joaquin Phoenix, semi-famous for his role in The Gladiator (1999), became a household name after starring as Johnny Cash in Walk the Line, and people like Jamie Foxx and Josh Brolin went from B-list actors to Hollywood stars after appearing in Ray (2004, dir. Taylor Hackford) and W (2008, dir. Oliver Stone) (fig. 11-12).

As Hal Foster (1996) says, we may currently be witnessing a “return of the real”, as markets are being flooded with political (auto)biographies (e.g. George W. Bush’s Decision Points [2011]), autobiographical fiction and mockumentaries (e.g. The Death of a President [2006], depicting the imagined assassination of George W. Bush), and documentaries and biopics about famous political figures (e.g. W). This alleged “return of the real,” however, only partly explains the American fascination with biopics, and another explanation, I argue, could be located in the personalized approach to history which is prevalent in the US.

History as a Personalized Narrative

The names D.G. Monrad and Orla Lehmann would hardly ring a bell to any Dane, let alone non-Danish people. However, these men have in fact been central to Danish history, signing the most central of all historical documents in Denmark – Danmarks Riges Grundlov (1849)– a document similar in national importance to America’s The Declaration of Independence (1776) (cf. Den store danske).

In the US, on the other hand, most people would know of the men who signed the aforementioned declaration – indeed, they are even recognized as “the founding fathers” – and this accounts for a central difference between the historical memory and conception in the two countries (cf. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYyttEu_NLU).

The biopic is not an unknown genre in Denmark, and biographical films and drama series have been made on iconic authors like Hans Christian Anderson (cf. Den unge Andersen, 2005), singers like Liva Weel (cf. Kald mig Liva, 1992), variety and film actors like Dirch Passer (cf. Dirch/A Funny Man, 2011), great inventors like Jacob Ellehammer (cf. Nu stiger den, 1966) and founders of successful national companies like Carlsberg (cf. Bryggeren, 1996-1997). Political biopics, however, are a rarity in Denmark – to put it mildly – and this reflects an entirely different approach to politics and political history in Denmark, compared to the US (fig. 13).

An All-American Hero: Lincoln as a fictionalized character

A natural figure on whom to base a political biopic is Abraham Lincoln, a former American president who is known for delivering such hugely popular speeches as “The Gettysburg Address” and “The Emancipation Proclamation” (1863), and who is – perhaps narrow-mindedly – remembered for having freed the slaves.

Hence, Lincoln, who sought a consensus and wished to free the slaves gradually, is widely recognized as an American hero, and unsurprisingly films have been made, depicting and dramatizing his already dramatic life. |

|

Fig. 11-12: Will Smith and Jamie Foxx both had their own sitcoms in the 1990s, but were not considered “serious” A-list actors until starring as Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali and Ray Charles, respectively, in Oscar nominated biopics).

Fig. 13: In Borgen (DR, 2010-) Sidse Babett Knudsen plays the first female Prime Minister of Denmark, a character that is often seen as a reflection of Helle Thorning-Schmidt (as of today, the actual Prime Minister of Denmark). The popular drama series, however, can hardly be described as a biographical show, in that Knudsen’s character is called Birgitte and in no way physically resembles Thorning-Schimdt (the main character in Borgen has also, on many occasions, been compared to Margrethe Vestager, a Danish politician representing Det Radikale Venstre. ). Political biopics are few and far between in Denmark, but in America the political biopic is a popular type of film, firmly rooted in Hollywood’s canon of genres. |

|

| |

Between Political Success and Personal Tragedy: Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln

An early fictional account of Lincoln’s life is seen in D.W. Griffith’s often overlooked talkie Abraham Lincoln (1930), a film dealing with “Abe” as a sort of tragic hero who succeeds in freeing the slaves and bringing The Civil War to an end, but suffers great personal tragedies.

In the very beginning of the film, Lincoln (Walter Huston) experiences a great loss, and as Lincoln comes to see his loved one, we see him in a grippingly personal scene, displaying his inner turmoil. Lincoln comes to see the young woman, who is desperately ill, and in a medium close-up (MCU) Lincoln is seen, trying to deal with the illness of his loved one and one particular line of dialogue: “Now, Abe, I must tell you the truth” (fig. 14).

As he enters the room, he sees the young woman lying in her bed; he paces the floor, takes off his hat and kneels in front of her, before she – in a strongly melodramatic exchange of dialogue – reminds him to “be brave” (fig. 15).

In this scene, like in many others from Griffith’s film, Lincoln is depicted as an emotional person, and his bravery is underlined in the dialogue, as it later is in his actions and speeches.

The film, in a sense chronicling Lincoln’s life, moves toward a climax, and the main character is seen (in a number of long shots) pacing around, thinking of how to deliver his “Emancipation Proclamation” (fig. 16). Naturally, the film ends in a tragedy, as Lincoln is assassinated in a theatre, thus creating a classically dualistic “tragedy – success” structure where political success and bravery are juxtaposed with personal turmoil and tragedy.

The Dual Structure of Abraham Lincoln (1930, dir. D.W. Griffith)

Griffith, who is widely known for his racist epic The Birth of a Nation (1915), shows a more humanistic quality in his political biopic about Abraham Lincoln, depicting its title character as a brave “Emersonian individual” and reminding us of the last stanza in Emerson’s poem “A Nation’s Strength” (1904):

Brave men who work while others sleep

Who dare while others fly

They build a nation’s pillars deep

And lift them to the sky.

(Emerson 2003, p. 43).

John Ford and the rise of Lincoln

Griffith’s film shows us the rise of Abraham Lincoln, from “humble origins to becoming one of the greatest orators of his and any other age” (cf. Pickwick Group Limited), but also his inevitable and tragic fall.

The 1939 film by John Ford, on the other hand, focuses solely on Lincoln’s ascendancy to become one of the key figures in American history and politics. In Ford’s film we follow Lincoln, convincingly played by Henry Ford, who leaves Kentucky to practice law, before going into politics.

The “great humanist”, John Ford, sees his heroic protagonist rise to the top, not only figuratively but also literally, as Lincoln’s final words are, “I think I’ll go to the top of that hill” – followed by a low angle shot of Lincoln climbing to the top of a hill, accompanied by the astounding “Battle Hymn of the Republic” (fig. 17).

“I’m Not a Crook”: Richard Nixon as a tragic hero?

If Abraham Lincoln is one of the most prominent, iconic and popular figures in American history, Richard Nixon is undoubtedly one of the most criticized and “villain-like” characters in American history.

From Strict Upbringing to National Disgrace: Nixon

For young movie goers (under the age of 30) Nixon will probably, aside from the history books, be remembered from Ron Howard’s gripping account Frost/Nixon (2008), about Nixon’s intense encounter with the journalist David Frost.

Twelve years earlier, however, in 1996, Oliver Stone made a memorable biopic called Nixon, starring a staggeringly persuasive Sir Anthony Hopkins in the film’s leading role and simply depicting reality ‘as the director sees it’ (cf. In Video Entertainment 1996).

“Paranoia, bitterness and revenge” function as the main themes in Stone’s movie, in which Nixon is at best a tragic hero, who may have had ideals, but who would soon come to be known for his scandalous cover-ups and political plotting (ibid.).

As is typical of Oliver Stone, the film uses fictionalized archival footage, creating an intense sense of authenticity, and the film establishes a certain sense of sympathy toward Nixon – however unrelenting it may seem – by going back to his strict upbringing and showing him as a young, impressionable boy (fig. 18). “JFK was a murder mystery,” the director says, while “this is a character mystery”, a character mystery trying to unlock and explain the enigma that is Richard Nixon (ibid.).

Stone has often been known for his political views – and largely seen as a political filmmaker – but going back to and dramatizing the childhood of Nixon, he focuses on Nixon as a private and essentially tragic character, providing us with a causal-psychological way of explaining or even justifying of Nixon’s actions. As Anthony Hopkins puts it in the featurette accompanying the dvd version of Stone’s film: “I think he’s a tragic figure, tragic to America also” (ibid.).

Politician Turned Boxer: Frost/Nixon

Whereas Stone, like Griffith, creates a fictional ‘cradle-to-grave like’ account of Nixon’s life, Ron Howard focuses on one specific and crucial event from 1977, a televised interview which would largely disgrace and discredit ex-president Richard Nixon.

The screenwriter behind the film, Peter Morgan, is hardly unfamiliar to the biopic genre, having earlier created The Queen (2006), in which Hugh Grant stars as the British Prime Minister (at the time) Tony Blair and Helen Mirren plays The Queen.

In Frost/Nixon we are not concerned with the hows and whys – how The Watergate scandal came about and why Nixon was so paranoid regarding his political opposition. Howard’s film, instead, is concerned with Nixon’s attempt to retouch or even recreate his image and the TV journalist David Frost’s attempt to resurrect his career in TV journalism. Howard’s film, characterized by film critic Peter Bradshaw as nothing more than a “talky, inert drama” (Bradshaw 2008), is, thus, reminiscent of a “boxing movie about two combatants who never meet outside the ring” (ibid).

As is typical of the genre, the film opens with (fictionalized) archival footage and captions illustrating the trials regarding Watergate and displaying the different people who were forced to resign on account of that political scandal (fig. 19). “As an American I found this story relevant,” says director Ron Howard, a story displaying “the breakdown in the citizens’ trust of their government” (Universal 2009). More acutely, though, the director points to the potential of describing the “alleged abuses of power” in the Bush administration of the time (2008; ibid).

However the film is conceived – whether it is seen strictly as a historical reminder or as an allegorical depiction of power abuse and misconduct in the US government – it hardly gives us a deep insight into the psyche of Richard Nixon.

Final remarks

In his own words, Frank Langella, who plays Nixon in Howard’s film, was “determined not to do an impression” (ibid.).

Even so, biopics have an inherent Oscar quality, given that actors have to mimic and (to some degree) impersonate a famous person – and polical biopics are often compelling and complex character studies in which tragedy and success are juxtaposed in various different ways.

The political biopic is not a new genre in America, and its prevalence in the Hollywood genre system is telling of its inherent qualities as a ‘star vehicle’ which feeds on a natural hunger for reality and history (in a way that seems harmless, even if it clearly represents a deeply individualistic conception of society).

The current boom of this genre may indicate a “return of the real” – a need for real stories about real people – but it also attests to a personalized conception of history which is popular in the US and American cinema (which clearly favors individualized causality) .

Audiovisual accounts of history, one might say, is but the political biopics of great (wo)men. |

|

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16.

Fig. 17: Abraham Lincoln rises to the top in Ford’s political biopic, The Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), a film recognized by Pauline Kael as “one of John Ford’s most memorable films” (cf. Twentieth Century Fox 2005).

Fig. 18.

Fig. 19: Authentifying footage from the beginning of Ron Howard’s Frost/Nixon (2008). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

Bibliography

Altman, Rick (2002): Film/Genre. London: BFI Publishing.

Bradshaw, Peter (2008): ”Frost/Nixon”, The Guardian. October 15th, 2008.

Den store danske (2012): “Den grundlovsgivende forsamling”.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo (2003): “A Nation’s Strength” (1904), in 101 Patriotic Poems. Boston et al: McGraw-Hill.

Foster, Hal (1996): The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. Chicago: The MIT Press.

In Video Entertainment (1996): “Featurette”, on the dvd version of Nixon. In Video Entertainment.

Nielsen, Jakob Isak (2011): “Leder: Bio pics”, 16:9 #43.

Pickwick Group Limited (2010): ”Back matter” on the dvd Abraham Lincoln.

Schepelern, Peter (ed.) (2010): Filmleksikon. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Schatz, Thomas (1981): Hollywood Genres. Boston, Massachusetts: McGraw Hill.

Twentieth Century Fox (2005): “Back matter” on the dvd The Young Mr. Lincoln.

Universal (2009): “The Making of Frost/Nixon”, on the dvd Frost/Nixon. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - februar 2012 - 10. årgang - nummer 44

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-12. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|