|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: With an Attitude

Af ETHAN DE SEIFE

Though he has taken on an increasingly wide range of acting roles since his début in 1991’s Boyz N the Hood, the rapper and actor Ice Cube is still strongly associated, even in his “family-friendly” films, with the trappings of gangsta culture. The development of Ice Cube’s star persona is an unusual one.

O’Shea Jackson, better known as the rapper Ice Cube, announced his arrival into global popular culture in 1988 on the first verse of the first (and title) song of Straight Outta Compton, the epochal début album by Los Angeles rap group N.W.A. (Niggaz Wit’ Attitudes). In that verse, Cube (1) declares menacingly,

Straight outta Compton, crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube

From the gang called Niggaz Wit’ Attitudes.

When I’m called off, I got a sawed off

Squeeze the trigger and bodies are hauled off.

You, too, boy, if ya fuck with me

The police are gonna hafta come and get me …

Here’s a murder rap to keep ya dancin’

With a crime record like Charles Manson.

AK-47 is the tool

Don’t make me act the motherfuckin’ fool …

So when I’m in your neighborhood, you better duck

‘Cause Ice Cube is crazy as fuck.

As I leave, believe I’m stompin’,

But when I come back, boy, I’m comin’ straight outta Compton.

(fig. 2)

The tone thus set, the album maintains a consistent level of ferocity for its duration, in large part due to Cube’s relentlessly stark declarations of his brutality. Straight Outta Compton, even today, remains harrowing.

A little more than twenty years later, in 2011, Ice Cube – now, according to his website, an “entertainment mogul” – won a NAACP Image Award, a prize that celebrates “the outstanding achievements and performances of people of color in the arts, as well as those individuals or groups who promote social justice through their creative endeavors.” The award, for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series, was for Cube’s recurring role on the TBS sitcom “Are We There Yet?,” a show based on the 2005 “family-friendly” road-trip/romantic comedy film of the same name, in which Cube plays a hapless bachelor placed in charge of two rambunctious children for the course of a zany road trip (“rzep” 2011). That a self-proclaimed “crazy motherfucker” could be thus awarded by the guardian organization of proper African-American culture is reflective of the two-pronged persona that Ice Cube has maintained for the better part of two decades: a scowling, gun-toting, ruthlessly murderous badass, as well as a goofy, wisecracking, broad-smiling family man. The awarding of such a prize to Ice Cube was not uncontroversial: at least one member of the clergy protested it on the grounds that Cube’s musical legacy was an offensive one (Powers 2011). |

|

(1) Numerous interviewers have written that the subject of this essay insists on being referred to not as “Mr. Jackson” or “O’Shea,” and certainly not “Ice”: “Cube” is his preference, so this essay follows that convention.

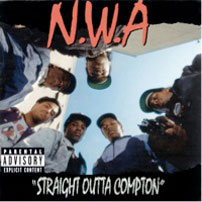

Fig. 2: M.C. Ren (Lorenzo Patterson), Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson), and Eazy-E (Eric Wright), “Straight Outta Compton,” from N.W.A.’s début album Straight Outta Compton (Hollywood: Ruthless Records and Priority Records, 1988). |

|

| |

Ice Cube’s ability to balance two starkly opposed personae is fascinating in and of itself, and appears at first to be somewhat contradictory, even hypocritical. But it is not especially uncommon for a star to maintain a multipart persona. The careers of both Vin Diesel and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, nonwhite actors of roughly Cube’s age, suggest useful points of comparison with that of Cube himself. Diesel and Johnson are primarily known as action heroes, but have also starred in comedies that typically cast them in decidedly “un-macho” parts, precisely for the purpose of lampooning the overpronounced masculinity of their action personae. Diesel’s The Pacifier (2005) and Johnson’s Tooth Fairy (2010) are the most prominent examples (fig. 3).

The two-part persona of Ice Cube, though, does seem to be a special case. His original persona – that of the streetwise “gangsta,” established when he was still in N.W.A. – is almost always folded into even his comic roles, such as those in Friday (1995) and even Are We There Yet? Whereas Johnson’s and Diesel’s comedies refer nonspecifically to the actors’ toughness and masculinity, many of the films in which Cube does not play a gangsta nevertheless include both direct and coded references to his upbringing “on the streets.” Despite his many and varied accomplishments in various media forms, Ice Cube is, however subtly, pegged as a gangsta in most (but not all) of his films. As I argue below, it is enlightening to draw upon certain concepts within hip-hop studies in order to gain critical perspective on this unusual situation. By charting the course of his film career, we may develop a sense of the factors at work in determining the development and meanings of Ice Cube’s unconventional star persona. |

|

Fig. 3: Vin Diesel, it must be noted, had the lead role in the first film in the xXx series; Cube had the second (see below). |

|

| |

My initial thoughts on the subject of Cube’s star image concerned the ways in which many African-American performers’ personae have been dishearteningly “softened” and made more palatable to predominantly white, mainstream audiences: the best example is surely Eddie Murphy, but the same may be said of performers as diverse as Morgan Freeman, Mo’Nique, and Terry Crews (2). The tempering or removal of the more challenging elements of a performer’s persona is not, however, a phenomenon peculiar to African-Americans, even if perhaps the most egregious examples do involve black performers (and even if this is a particularly long-standing and fraught issue in African-American culture and studies). Caucasian performers whose personae include potentially challenging or difficult facets – Jim Carrey, John Belushi, Judy Garland – have all been “toned down” for the purpose of broadening their appeal and, thereby, their commercial potential.

While the softening of the personae of African-American performers may seem especially pronounced, it would be wrong, I think, to attribute it entirely to some sort of racism; as usual, profit is the more powerful motive. Joe Roth, an executive producer at Revolution Films, the studio that produced Are We There Yet?, noted, shortly before that film’s release date, “Kids see Cube as a cool guy, and if they can pressure their parents to take them, we’ll have a crossover movie. The great thing about the nag factor [kids pressuring their parents to take them to a particular movie] is that it’s beautifully without prejudice” (Goldstein 2005). But even if it was strictly an economic decision to tone down Ice Cube’s persona to make it “kid-friendly,” shreds of what appear to be stereotypical practices remain: in Are We There Yet? and other of his lighter films, Cube’s characters are burdened with the signifiers of a specifically African-American criminality. |

|

(2) Cube has commented, in fact, that he does not intend “to turn into Eddie Murphy and start just doing kids’ movies because they work. … I’m not trying to go in that direction with my career.” (Armour 2005). |

|

| |

The Nature of Persona

Many popular periodicals have printed articles on the malleability of Ice Cube’s star persona, typically published around the release dates of certain of Cube’s films: Boyz N the Hood (1991), Friday, Three Kings (1999), Are We There Yet?, and xXx: State of the Union (2005). Briefly, Boyz N the Hood is significant for showing that Ice Cube could not only act, but could act well; Friday, for being the first of his film projects to suggest a variation to Cube’s gangsta persona; Three Kings, for Cube’s appearance in a more “artful” film than any of his previous works; Are We There Yet?, for introducing Cube’s “warm and fuzzy” side; and xXx: State of the Union, which premiered just three months after Are We There Yet? (Source: IMDB), for casting Cube in what appears to be a highly un-gangsta-like role. Indeed, these films are the nodes around which Ice Cube’s star persona has coalesced, and are discussed in detail below.

“Star images are always extensive, multimedia, intertextual,” writes Richard Dyer in Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (Dyer 2004, p. 3). To pin down a star image sufficiently to actually define it is a tricky task, especially since the texts that comprise it are so plentiful and ephemeral: press kits, television commercials, movie posters, and print advertisements play a tremendous role in establishing and codifying any and every star’s public persona (or “image,” to use Dyer’s term). When a star’s persona consists of multiple or even contradictory elements (as is the case with Ice Cube), the task is even more challenging. Moreover, a star persona is not strictly quantifiable; it is more like a collection of associations, as very generally agreed upon by fans, critics, agent, casting directors, and public-relations workers. Star personae are immensely multifaceted, even as they usually coalesce around a handful of well-defined qualities.

For the most part, this essay uses “tentpole” media texts – that is, Ice Cube’s films themselves – in analyzing his star persona. A longer version would incorporate such materials as are listed above, but space constraints make such investigations challenging. In any case, restricting the analysis to the films permits a focus on how film itself intersects with the complicated notions of performance and persona. |

|

(3) The phrase “warm and fuzzy” is used in the headlines of at least two lightweight articles on Ice Cube from January 2005: see Daly (2005) and Goldstein (2005). Armour (2005) even goes so far as to refer to the star as “huggable.” |

|

| |

From Gangsta to Soldier

On the cover of N.W.A.’s début album Straight Outta Compton, group member Eazy-E (Eric Wright) points a gun directly into the camera, and Ice Cube himself, then just 19, displays the scowl for which he would soon become well-known. Cube’s performative persona was established – and largely fixed – by his work with N.W.A., a group whose centrality to and influence on the subgenre of gangsta rap remains unchallenged. Straight Outta Compton is a tremendously angry record: many of its songs refer, in brutal language, to vicious gang violence and the war between white police and black Angelenos. The album is one of the relatively small number of first-wave gangsta rap albums to receive nearly unanimous praise from music critics; this landmark record was a sensation upon its release, and its reputation has not tarnished in the ensuing decades (4). While obviously not a cinematic text, it merits mention here as the font of nearly all of the associations and contexts that have informed the entirety of Ice Cube’s career. |

|

(4) A brief summary of the critical response to Straight Outta Compton is available here (last visited 9 August 2011). |

|

| |

Once Ice Cube was known and recognized as a member of N.W.A., his image as a gangsta was all but indelible. Cube himself did little to alter this persona in the first years of his solo career: his first three solo albums – AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (and its follow-up EP, Kill at Will, both 1990), Death Certificate (1991), and The Predator (1992) – all reside squarely within the gangsta rap subgenre, and, if anything, see Cube’s anger intensify, even as it becomes more politically astute and finely focused (fig. 4-7). On these records, Cube solidified his reputation as a hard-as-nails, angry, even vicious young man, a fact stressed in many reviews of these albums. Entertainment Weekly’s somewhat favorable review of AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, for instance, remarks that Cube is “angrier than he was with N.W.A.,” refers to him as “caustic” and “uncompromising,” and notes that the album’s de facto argument is that “violence is everywhere; nothing can stop it; you have to get a gun just to survive.” (Sandow 1990). That summary, which tidily encapsulates the overarching themes of Cube’s first records, crucially underpins Cube’s transition from rapping to acting.

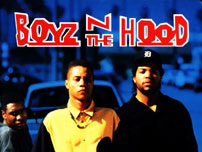

John Singleton’s début feature Boyz N the Hood (5) is also Cube’s début film performance (5). He plays Darren “Doughboy” Baker, a recently paroled gang member who is the film’s most hotheaded, aggressive, and violent character: Sonny Corleone to the Michael-like Tre (Cuba Gooding, Jr.), the film’s protagonist. Doughboy not only refers often to the everyday violence that is part of daily life in South Central Los Angeles, but threatens his rivals with guns, and kills several members of a rival gang in retaliation for their killing his half-brother, Ricky (Morris Chestnut). In an epilogue, Doughboy is revealed to have been murdered himself, a victim of the code of violence by which he lived.

In Boyz N the Hood, Doughboy is the character most strongly associated with aggression, violence, and L.A.’s gang wars; he accepts it as a fact of life, while all of the other central characters do what they can to escape the violence that surrounds them. There is little in the character of Doughboy that was not already a facet of Ice Cube’s established persona. Indeed, a fair number of reviews of the film suggest that Ice Cube drew heavily from his life experience for his first film role. Desson Howe in The Washington Post writes that Cube is “tremendously believable” (Howe 1991); Janet Maslin in The New York Times even goes so far as to praise Cube for his “street swagger.” (Maslin 1991). Comments such as these are code to suggest that Cube “played himself” in the film – rather a lazy characterization, even if most critics praised Cube’s performance. The typical response in the popular press was a combination of astonishment that a tough-guy rapper could actually act, and sincere praise for Cube’s abilities. Kenneth Turan wrote that Cube’s performance was “unexpectedly affecting” (Turan 1991); The New Yorker’s Terrence Rafferty called it “complex [and] magnetic,” suggesting, not unreasonably, that it is the best feature of the film (Rafferty 1991).

Given the strength and visceral force with which Ice Cube established his rap persona, it is unsurprising that his first film role also casts him as a ruthless gangsta – indeed, it was positively calculated. It would have been, from an economic standpoint, far riskier to offcast Cube for his first role than to cast him in such a way that confirms audiences’ expectations of him: as a gangsta in South Central Los Angeles, the exact milieu of Cube’s early-‘90s albums, as well as Boyz N the Hood. Singleton’s film neatly transfers Ice Cube’s rap persona wholesale to the medium of film, and, in so doing, stamped Cube with a near-indelible set of performative associations.

That Boyz N the Hood deliberately and strongly evokes Ice Cube’s gangsta associations is evident in the film’s official trailer, a text that also demonstrates the importance of Cube to the film’s promotional strategies (fig. 8). The trailer opens with the sounds of a police siren and a voiceover: “This is Los Angeles, gang capital of the nation.” The next sound we hear is Cube’s voice delivering what has generally come to stand as the film’s moral. As a medium close-up of Doughboy is intercut with slow-motion shots of Tre running through an alley, Cube says, “It just goes on and on, you know? Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what’s goin’ on in the ‘hood.” The sound of a shotgun blast ends this introductory segment. Right from the start, Ice Cube and the character he plays are associated with gang violence. Even this famous line, delivered so defeatedly, nevertheless enhances Cube’s association with gangsta life. Later in the trailer, we see Doughboy brandishing a gun, an image introduced by a voiceover: “Doughboy was living by the laws of the street.” The last minute of the trailer is accompanied by Ice Cube’s song “How to Survive in South Central,” a darkly comic instructional guide to being ‘hood-savvy that contains such lyrics as “Rule Number One: get yourself a gun.” Despite the fact that it was his first role, Ice Cube receives top billing in the list of credits at the end of the trailer, ahead even of Larry Fishburne, the best-known performer in the film, and Cuba Gooding, Jr., who plays the central role. Cube, and his gangsta associations, are central to the marketing of Boyz N the Hood, and are crucially integrated into the narrative of the film itself. Boyz n the Hood is vitally important in fixing the gangsta persona that Cube has carried with him ever since.

Cube’s next several films – notably his second, Trespass (1992), in which he plays another Sonny Corleone-like gangster – do nothing to vary the contexts most closely associated with his persona: crime, thuggishness, and a devil-may-care attitude toward life, death, and violence. The first major variation of Cube’s persona may be found in Friday, a film he also cowrote and executive-produced. Yet this crucial change, even if self-initiated, does not vary his gangsta persona as much as it may appear to do.

Friday is a charming, shambolic comedy that lacks – or, rather, deliberately avoids – many of the trappings of classical Hollywood storytelling, such as goal-oriented protagonists and an intertwined romance/action plot. It is a highly episodic film in which the protagonists (including Cube’s character, Craig) are far more inactive than active: for most of the film, they sit on the porch of Craig’s house, observing the humorous actions of the eccentric residents of their neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles (see also my blog post on the film).

Friday is Cube’s first comedy, albeit one that probably could not have been made without the critical and commercial success of the early-1990s wave of films about young male African-Americans embroiled in gang violence: Boyz N the Hood is the nexus of a cycle that includes New Jack City (1991), Straight Out of Brooklyn (1991), Juice (1992), Menace II Society (1993), and others (fig. 9).

Craig is by no means a gangsta: He is a friendly and well-meaning if somewhat irresponsible young man who is frustrated with his job, and who is not quite ready to leave the nest of his parents’ home. His day-to-day concerns are the stuff of teenage suburban angst: girls, jobs, boredom. Yet Craig’s neighborhood, like Doughboy’s in Boyz N the Hood, is in South Central Los Angeles; he and his friend Smokey simply take as given that they are surrounded by and unavoidably involved with drug dealers, desperate crackheads, thuggish neighbors, and violent gang members. In the film’s most jarring tonal shift, a scene of light banter on the porch is interrupted when the drug dealer to whom Smokey owes money sends his thugs to extract payment in blood. When Craig and Smokey clamber over the roof to avoid the hail of machine-gun fire, director F. Gary Gray plays it for laughs: it is more a comic set piece than a scene of genuine terror.

Another tonal shift occurs near the end of the film, when Craig, a self-professed pacifist, procures a gun to finally rid himself of Deebo (Tiny Lister), the relentless neighborhood bully. Craig’s father (John Witherspoon) – who until this point has mostly been the locus of the film’s toilet humor – finds his son with a gun in his hand, earnestly urges him to put it away and, if need be, stand up like a man and challenge Deebo to an old-fashioned fistfight. This scene strongly and deliberately echoes a key scene in Boyz N the Hood, in which Furious Styles (Fishburne) delivers a nearly identical lecture to his son, Tre. That Craig, a good-humored young man, opts so readily for a firearm as a solution to his problems – and, indeed, that he shortly thereafter defeats Deebo in a fairly violent fistfight – reflects the fact that, for all its geniality and lightweight comic antics, Friday is a film that is crucially informed by the context of Los Angeles’s African-American gang violence. Moreover, even as Cube’s persona is expanded and enriched by the addition of a genuine comedic dimension, it cannot completely escape the gangsta trappings that defined it since the release of Straight Outta Compton. Performatively, Friday was a significant leap for Cube: he had never attempted comedy before, and demonstrates a facility for it. However, with regard to his persona – the collection of both textual and extratextual associations and signifiers – the distance that he vaulted was not altogether that vast.

Proceeding chronologically to the next of the five films that are the nodes of the development of Ice Cube’s star persona (passing over such films as Dangerous Ground [1997], I Got the Hook Up [1998], and Thicker than Water [1999], all of which rely heavily and uncomplicatedly on Cube’s gangsta image), we find perhaps the only film in Cube’s acting career that dissociates itself completely from his original persona. Three Kings, a sardonic satire set in Iraq in the waning days of the 1991 Gulf War, casts Cube as Staff Sergeant Chief Elgin, a working-class man from Detroit who joins Major Archie Gates (George Clooney), Sergeant Troy Barlow (Mark Wahlberg), and Private Conrad Vig (Spike Jonze) in a scheme to decode a treasure map (recovered from the derriere of an Iraqi prisoner) in order to locate and make off with millions of dollars of gold bars that had been stolen from Kuwait by Saddam Hussein. It is Cube’s eleventh feature film.

Three Kings is a challenging film on many levels: its political satire is double-edged and ambiguous (if quite incisive); its striking visual style, largely a result of the Ektachrome stock on which it was shot, is potentially disorienting; and, more pertinently, it dissociates at least one of its three lead actors from his established persona. Nowhere in the film is Cube’s character associated with any of the trappings of gangsta life. Neither does Chief possess a hotheaded temperament – indeed, he is the most even-tempered of the three leads, and is in fact a devout (if opportunistic) Christian who speaks often of the “ring of Jesus fire” that protects and guides him. The film states repeatedly that Chief, a baggage-handler back in Detroit, is a regular blue-collar worker – not a gangsta, not a comic variation of a gangsta, not a man whose life is informed in any way by any of the recurring elements of Ice Cube’s persona.

It is difficult to say exactly why, of all his films, it is Three Kings that is most successful in changing and enriching Ice Cube’s persona, especially when he had a greater degree of creative control over such films as Friday, which he cowrote and executive produced; Dangerous Ground, which he executive produced; and The Players Club (1998), which he wrote, executive produced, and directed. Cube may have simply liked the script for Three Kings, or he and his managers may have decided that his gangsta persona was sufficiently well established to withstand any variations offered by the film. It is worth noting, however, that Three Kings, as suggested above, is a somewhat challenging film in a number of other ways, as well; it may be useful to consider Cube’s offcasting as part and parcel of director David O. Russell’s unconventional vision for his film. Three Kings’s political satire is potentially objectionable; its “message,” if indeed it has one, is ambiguous at best; its narrative leaves a number of questions unanswered and motives uncertain; it is an odd mix of war film, heist film, and dark comedy; its visual style, which mixes bleached-out desert vistas with impossibly supersaturated Ektachrome-shot violence, is beautifully odd and unsettling; and, most pertinently, it is a film that varies the persona of another of its leads, George Clooney. Prior to Three Kings, Clooney, then best known for his role as Dr. Doug Ross on the television series ER, had had some success in features as both romantic lead (One Fine Day, 1996) and action hero (Batman & Robin, The Peacemaker, both 1997) but had not yet firmly established his film persona. Three Kings, a black comedy that casts him as a cynical, intelligent, rakish yet honorable career military man with no tolerance for bureaucracy, was perhaps the linchpin in establishing the persona on which Clooney would rely in his successful leading-man career in the 21st century: we see echoes of his Three Kings persona in O Brother, Where Are Thou? (2000), Ocean’s Eleven and its sequels (2000, 2004, 2007), Intolerable Cruelty (2003), and Up in the Air (2009), among others. That Three Kings varies one of its leads’ personae suggests that it is likely to vary that of another.

From PG to xXx

In 2005, Ice Cube appeared in two films that appear radically different: the family-friendly comedy Are We There Yet? and the action film xXx: State of the Union. As I will suggest, though, while Cube may execute pratfalls in the one and scowlingly leap onto airborne helicopters in the other, both films offer only slight variations of his gangsta persona. Three Kings suggested for his persona a number of compelling variations, but he appears not to have taken the film up on its offer.

Are We There Yet?, a sloppily made film that nevertheless inspired both a sequel and a TV series, subjects Cube, in the name of comedy, to such indignities as having a gigantic prop axe fall directly on his genitals, and being roundly thrashed by a frenzied deer. His character, Nick, is a dealer in sports memorabilia who subjects himself to the challenges of taking two unruly kids on a road trip so that he may endear himself romantically to their mother, Suzanne (Cube’s frequent costar Nia Long). Even though the film is a goofy romantic comedy and Nick is a good-natured if somewhat childish suitor, Cube’s persona in this film operates under the “gangsta” shadow that informs nearly every one of his roles. |

|

Fig. 4-7: Ice Cube’s first four solo albums, all released between 1990-92: AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Kill at Will, Death Certificate, and The Predator.

(5) The title of the film is derived from the 1987 song “Boyz-n-the-Hood” by Eazy-E, Ice Cube’s bandmate in N.W.A. Cube cowrote the song.

Fig. 8: A regrettably low-resolution version of this trailer is available on YouTube (last visited 10 August 2011). A better version is available on the various DVD releases of the film.

(6) Indeed, on the solo albums that he released around this time, Ice Cube had begun to address his regret for the gangsta lifestyle, and to lament the fact that gang violence had so destroyed urban African-American life. Such sentiments may be found on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Kill at Will, and Death Certificate, all released between 1990-1991.

Fig. 9 Perhaps the truest mark of this cycle’s impact is that fact that its films are the target of at least two parodies: Fear of a Black Hat (1993), and Don’t Be a Menace to South Central while Drinking Your Juice in the Hood (1996). |

|

| |

Nick bears a number of pronounced marks of the urban African-American gangsta, a motif introduced during the opening credits, the first time we see Cube in the film. Our first view of Nick, which plays under Ice Cube’s name-above-the-title credit, is of just his torso, on which he wears not just a plush “pimp” coat and an oversized sports jersey, but two large, shiny, silver necklaces (fig. 10). The pimp gear, sports gear, and “blingage,” as Nick refers to it, are strong indicators of thuggish hip-hop identity. Next is a long shot of Nick from behind, over which is superimposed the film’s title, the dot of whose question mark is animated to resemble a moving “spinner,” a type of shiny, expensive, status-declaring hubcap that continues rotating even after its vehicle has come to a stop (fig. 11). These automotive accoutrements are not only strongly associated with crime-ridden urban African-American neighborhoods, but appear in physical form on Nick’s own SUV, another symbol of his gangsta identity – one that is eventually destroyed by its two youthful, obstreperous passengers.

A later scene emphasizes Nick’s gangsta identity even more strongly. In one of their many efforts to rankle him, the kids insist on playing the exceedingly irritating novelty song “The Hampster [sic] Dance” on his car stereo. Nick responds, using “urban” phraseology, “No. No! One thing you gotta know up in here: that we keep it real. You can belie’ that”; he then proceeds to play a CD of 50 Cent’s aggressive anthem “What Up Gangsta.” Nick refuses the kids’ request to instead play Justin Timberlake or Clay Aiken, saying, “Did you know you can get shot for playing those kinda CDs in my old neighborhood?” Nick is strongly identified as a gangsta, by his preference for the music of 50 Cent, by the words and pronunciations thereof that he employs, and, most saliently, by his reference to the gang violence of his old neighborhood. He may be a reformed gangsta who is ready to settle down with Suzanne, but he is still a gangsta. For as much as it seems that Are We There Yet? was a massive break in Cube’s career, the film nevertheless relies strongly on gangsta signifiers. The only surprising thing about Cube in Are We There Yet? is not that he took on the lead in a milquetoast kids’ movie, but that that milquetoast kids’ movie refers directly to the gangsta subculture.

The laboriously titled xXx: State of the Union, released just three months after Are We There Yet?, is the most thoroughgoing attempt to make of Ice Cube a bona fide action hero. In the film, Cube plays Darius Stone, a tough, Tupac-quoting former Navy SEAL who “came up on the streets” of Washington, D.C., and who has been incarcerated for nearly a decade after being doublecrossed. In this film, fragments of the mythos of Ice Cube himself are folded into the character of Stone: once again, Cube may be said to be “playing himself,” a notion that hinges on his identity as a gangsta. |

|

Fig. 10 and 11: The coding of Nick as a gangsta in Are We There Yet? |

|

| |

About 25 minutes into the film, employees at a top-secret, subterranean NSA facility are briefed on Stone’s background. As an agent speaks of Stone’s various crimes as well as his elite military training, one of the images that flashes on a giant computer screen is a photo of Ice Cube that was almost certainly taken during his time with N.W.A. In it, Cube sports a number of gangsta signifiers (fig. 12): a braided gold “dookie rope”; a thin, lip-hugging moustache; his familiar angry scowl; the Jheri curls for which Cube was well known; and a black Los Angeles Raiders baseball cap of a style particularly popular in the late 1980s. While it is not necessarily uncommon for a film to use photos from an actor’s past to enrich the depiction of his or her character’s past, this brief but important scene goes further, drawing specifically and directly on Cube’s past – and his persona – to enrich his character, effectively conflating the two.

The conflation of star and character occurs at least once more in the film: when a character notes that the political milieu of Washington, D.C., is a “snake pit” in which everyone fights for a small piece of turf, Stone offhandedly remarks that it “sounds a lot like where I grew up.” Though Cube is from L.A. and Stone is from D.C., the evocation of gang turf wars – such as the one between The Crips and The Bloods in Los Angeles, to which Boyz N the Hood alludes – is quite clear. It seems odd that the gesture of referring to the “old neighborhood” links Are We There Yet? and xXx: State of the Union, two films that superficially appear to have little in common, and whose disparities have indeed come to signify Cube’s performative versatility (see, for example, Donahue 2005). And yet, as I hope to have shown, that linkage, which hinges on Cube’s gangsta persona, is not only unsurprising but practically guaranteed: even when he is not playing a gangsta, Ice Cube is strongly coded as one. It is an amalgamation of associations that has persisted, despite numerous apparent attempts to vary it, for more than two decades.

Gangsta Gangsta

“It’s about my persona.

Ain’t nothin’ like a man that can do what he wanna”

(Ice Cube, “Gangsta Rap Made Me Do It”)

Like those of every star actor, the components of Ice Cube’s persona are largely determined by economic factors: what is the star image that the greatest number of people will pay to see? In running his own production company and maintaining a high degree of both fiscal and creative control over his projects, Cube seems to be a savvy businessman who has taken the maintenance of his star image into his own hands. “A lot of doors are opening because of the rap records that I do, and I would be a fool not to step through them,” he has said. “The movies have taken my career to a whole new level. I’m going to take advantage of it” (McIver 2002, p. 156).

Though it may seem to violate some sort of code of hip-hop honor, Cube has unapologetically embraced the apparent diversification of his persona by taking on such projects as Are We There Yet? (and its spinoffs) and the 2002 film Barbershop (and its spinoffs). In an interview, Cube remarked, “[P]eople know me as one way, hardcore, a bad motherfucker, and that’s cool. But the fans wanted [a film like Friday] and you got to give the fans what they want. Or you’re just playing into the hands of the doubters” (Leigh 2000). He has made similar remarks in many interviews over the last fifteen years. Cube gets to have it both ways: in certain films, and on most of his albums (including his most recent, 2010’s I Am the West), he still overtly maintains the image of a gangsta, even as he has appeared in enough films of various types to make it appear that he has diversified that image significantly. Yet he gets to have it two ways in another way, as well: should Cube be taken to task within the hip-hop community for “selling out,” he would be justified in pointing out that even his unconventional roles in family-friendly comedies maintain a certain gangsta essence: he has remained true to his roots, after all.

There is yet a third way in which Ice Cube gets to have his cake and eat it, too; it relates to one of the contradictions that has undergirded hip-hop for its entire existence. Alan Light, in “About a Salary or Reality? Rap’s Recurrent Conflict,” writes about two opposing notions that have long imbued rap music with a certain inconsistent (if not paradoxical) nature: “keeping it real” and “getting paid.” Noting that rap is “full of complications, contradictions, and confusion,” Light details the tensions between “street” rappers, whose music addresses the harsh realities of ghetto life, and pop-oriented rappers, who are more concerned with reaching as wide an audience as possible, even if that means making inoffensive records that avoid altogether the issue of gangsta culture (Light 2004, p. 138). Intriguingly, hardcore rappers are far likelier to rap about “getting paid”: reaping monetary success by rapping skillfully. The most problematic contradictions have come to the fore when hardcore rappers have achieved commercial success, since gaining wealth instantly negates the ghetto/gangsta status that is so often the subject of their songs. In rap’s boom years – the mid-1980s to early 1990s: a time when the genre achieved tremendous mainstream popularity and chart success – “a dichotomy was firmly in place,” writes Light. “Rappers knew that they could cross over to the pop charts with minimal effort, which made many feel an obligation to be more graphic, and attempt to prove their commitment to rap’s street heritage” (Light 2004, p. 142). Light even singles out N.W.A. for mounting an “unprecedented” challenge to the pop charts by titling one of their songs “Fuck tha Police.”

Inasmuch as rap music, and hip-hop culture in general, fixates on the contradictory notions of both gangsta authenticity and unapologetic moneymaking, Ice Cube’s persona may be said to embody much the same dichotomy, and may usefully be understood to have its origins in that same contradiction. This is not to say that rap “does not make sense,” or that Cube is a hypocrite; just that both the genre and the performer operate under some of the same inconsistencies, which, indeed, may very well be the source of their force and popularity. Not only do these two contradictory hip-hop notions justify Cube’s appearance in unchallenging, mainstream films, but the gangsta image that in fact undergirds nearly every one of his film performances strengthens his identity as a performer associated with ghetto street culture. Though he may seem to have strayed far from the hardcore fold, Ice Cube’s multifaceted persona resolves itself, ironically, into the same aggregation of gangsta associations that have followed him around since the late 1980s, when O’Shea Jackson reinvented himself. |

|

Fig. 12: Ice Cube/Darius Stone as a young gangsta in xXx: State of the Union. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

Bibliography

Armour, Terry (2005). “Ice Cube’s Road Trip to Movie Stardom,” Chicago Tribune, 21 January 2005; available at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2005-01-21/features/0501210005_1_o-shea-jackson-cube-vision-ice-cube.

Daly, Sean (2005). “The Warm and Fuzzy Side of Ice Cube,” The Washington Post, Vol. 128, Issue 45, 19 January 2005, pp. C1 + C12.

Dikkers, Scott, ed. (1999). Our Dumb Century: 100 Years of Headlines from America’s Finest News Source (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999), p. 157.

Donahue, Ann (2005). “The XXX Factor,” Premiere (Vol. 18, No. 8, May 2005), pp. 88.

Goldstein, Patrick (2005). “Ice Cube Crosses over to Warm and Fuzzy Side”, The Los Angeles Times, 25 January 2005.

Howe, Desson (1991). “Boyz N the Hood” (review), The Washington Post, 12 July 1991.

Leigh, Danny (2000). “Chillin’ with Cube,” The Guardian, 25 February

2000, p. 6.

Light, Alan (2004). “About a Salary or Reality? Rap’s Recurrent Conflict,” in Murray Forman and Mark Anthony Neal, eds., That’s the Joint! The Hip-Hop Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004).

Maslin, Janet (1991). “A Chance to Confound Fate” (review of Boyz N the Hood), The New York Times, 12 July 1991.

McIver, Joel (2002). Ice Cube: Attitude (Surrey, UK: Sanctuary Publishing, 2002), p. 156.

Powers, Shadi (2011). “Ice Cube Wins NAACP Image Award???,” Hip Hop Weekly, 5 March 2011.

Rafferty, Terrence (1991). “Boyz N the Hood” (review), The New Yorker.

“rzep” (2011). “Ice Cube & Coors Light: The Coldest Partnership…,” icecube.com.

Sandow, Greg (1990). AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (review), Entertainment Weekly, 25 May 1990.

Turan, Kenneth (1991). “L.A. ‘Boyz’ Life: Growing up in South Central – A Gritty ‘Boyz N the Hood,’ Los Angeles Times, 12 July 1991. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - september 2011 - 9. årgang - nummer 43

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-11. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|