|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: The Branding of an Author: William Castle and the Auteur Theory

Af ETHAN DE SEIFE

Exploitation filmmaker William Castle’s legacy is staked far more firmly on his acumen for ballyhoo than it is on his filmmaking talents (fig. 1). Castle is certainly a better filmmaker than he is usually considered to be, but my chief aim here is not necessarily to elevate him to the rarefied ranks of film auteurs. The case of William Castle is fascinating because it both encourages us to question and challenge the very notion of cinematic authorship and provides us with an unusual opportunity to study how the concept of authorship has evolved, changed, and, arguably, even been inverted.

William Castle’s extracinematic skill for ballyhoo – on which he quite possibly rewrote the book – surely deserves to be acknowledged. John Waters, Castle’s foremost acolyte, reveres his idol (whom he dubs, within the space of two paragraphs, “King of the Gimmicks,” “the greatest showman of our time,” and no less than “God”) precisely for Castle’s mastery of gimmickry, lamenting the fact that, since Castle’s death, the art of showmanship seems to have been lost (Waters 2003, p. 14). Castle stands out for bringing the practice (art?) of movie exploitation to an apex; his famous gimmicks are irresistibly brash and fun, and seem today like artifacts from the Grand Old Days of cinema. A modern multiplex may display in its lobby a motorized cardboard stand-up of Harry Potter astride a broom, but William Castle flung skeletons out on wires over the heads of his audiences and rigged joy buzzers to their seats. They just don’t do that kind of thing anymore.

Fondly remembered though they are, such acts of inspired silliness almost inevitably detract from any artistic legacy Castle might otherwise have acquired. But can authorship even exist at the “lower strata” of the film industry? Are there auteurs among the ranks of straight-to-video exploitation films, industrial films, pornography? To answer in the negative is to assert a bias that authorship is largely determined by matters of taste and economic might. To answer in the affirmative is to extend logically the original mission of authorship criticism: to find artistic value in previously overlooked cinematic forms. Still, though, to argue for the existence of auteurs of, say, industrial films may be to weaken the notion of authorship to a point at which it is no longer useful.

Authorial Signatures

Andrew Sarris famously claimed that the first premise of the auteur theory is “the technical competence of a director as a criterion of value” (Sarris 2001 [1962], p. 586). Though William Castle worked in low-budget film – a stratum of cinema production typically associated with “artfulness” only in the cases of reclaimed auteurs like Edgar G. Ulmer – Castle was no seat-of-the-pants hack. While not a top-flight directorial talent, Castle’s filmmaking skills, honed over decades in the industry, surely eclipse those of his contemporaries such as Ed Wood, Jr., and Arch Hall, Sr. On the other hand, Castle was nowhere near as talented as the Alfred Hitchcocks of the world. While it may be too harsh to call his films pedestrian, it is not inaccurate to refer to them as average or standard.

Another measuring stick of Castle’s authorship status is Sarris’ second premise: that a director must “exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature” (ibid., p. 586). I am mostly concerned with Castle’s late-career renaissance as exploitation filmmaker in the late 1950s and onwards, but it must be acknowledged that Castle directed films from the early 1940s – mostly low-budget potboilers and genre films for Columbia Pictures. Even if one exempts Castle’s early career it is difficult to locate a coherent authorial signature at the level of Castle’s use of cinematography, editing, or mise-en-scène, and it is equally difficult to make such claims on the basis of his films’ narrative techniques or thematic content. Indeed, in discussing low-budget and exploitation cinema, questions of style such as these are less important than questions concerning audience engagement, topicality, promotional strategies, gimmicks, and budgets. |

|

Fig. 1. Castle about to carve a piece out of Hitchcock. It is difficult to know exactly how to refer to Castle’s filmmaking niche. His films were not “A” pictures; nor were they “exploitation” pictures in the sense in which that term is used by Eric Schaefer when addressing such “low” subgenres, with which Castle had no truck, as the burlesque film and the sex hygiene film. In most of the literature on his work Castle is referred to as an “exploitation filmmaker,” even as his films are probably closer to “B” movies. Castle himself confuses the issue, referring to his films as “modest-budget exploitation pictures,” even as his own autobiography’s title refers to his career in B movies. See Castle (1992, pp. 165), Taves (1993) and Schaefer (1999). |

|

| |

Film style for Castle was not unimportant, but it was not going to interfere with the delivery of thrills, shocks, or gimmicks (fig. 2). If a clever use of cinematic technique could complement a film’s ability to thrill, that suited Castle fine: style was just another item in the toolbox, to be found in the compartment next to the flying skeletons. This is not to say, however, that William Castle films are not identifiable as such. Watch a handful of Castle’s exploitation films and one feature quickly stands out: the introductory segments, in which Castle himself usually appears and speaks directly to the camera. In these segments, Castle assumes the role of avuncular, if slightly creepy, master of ceremonies for the ghoulish events that, he gleefully insinuates, are soon to follow.

Uncle Bill’s monologues are usually good for a pun or two, or a silly sight gag, thus preparing audience members not only for scares, but for the jocular humor with which they are presented. Audiences soon came to expect and enjoy these good-natured introductions, which became as important an imprimatur of Castle’s brand as the famous silhouette icon, found on many of his movies’ posters, of a cigar-chomping Castle sitting cross-legged in a director’s chair (fig. 3). Along with the logo and Castle’s name “above the title on every marquee,” these introductions strengthened what would nowadays be called “The William Castle Brand” (Castle 1992, p. 159). Furthermore, they suggest that the notion of authorship – especially as it intersects, often uncomfortably, with the notion of branding – may offer new ways to understand Castle’s films.

Hitching His Wagon to Hitch’s

Castle often compared himself to Alfred Hitchcock, whom he referred to as “the master” and “the great man” (Castle 1992, pp. 9 & 160). Castle, too, worked primarily in the thriller/suspense genre, and he evokes Hitchcock often in his own films. The most obvious case study is Castle’s 1961 film Homicidal, which concerns a psychotic transgendered murderer and was released almost exactly a year after Hitchcock’s Psycho, which concerns a psychotic transvestite murderer. In his autobiography, Castle acknowledges that his impetus for devising this gimmick was to top Hitchcock’s own gimmick for Psycho: that no one was allowed into the theater once the film had begun (ibid., p. 155). With Homicidal, Castle pulled off a kind of exploitation perfecta: the film cashes in not only on the controversial subject of sex reassignment surgery (Christine Jorgensen’s name still appeared regularly in headlines in the early 1960s), but on the succès de scandale of Psycho itself.

Castle deliberately emulated Hitchcock in more ways than merely copying and intensifying the shock value of certain plot elements. His introductory segments were modeled on Hitchcock’s celebrated cameo appearances in his own films, and serve many of the same purposes (ibid., p. 160). Hitchcock’s cameos and Castle’s introductions both invite audiences to engage with the films on a ludic level: Hitchcock invites his viewers to play the “Where’s Hitchcock?” game (fig. 4), and Castle, in assuming an amiable tone and speaking directly to the camera, encourages a playful approach to his films, even the gory ones. More importantly, both Hitchcock’s and Castle’s appearances in their respective films provide not just visible proof of authorship, but visible assertions of authorship. By including themselves in their films, the two directors claim, in no uncertain terms, that they are the parties responsible for the creation of those films. Their appearances are signatures written in especially bold letters. As well, Hitchcock’s and Castle’s appearances in their own films act as marks of quality and of brand identity. The inclusion of a Hitchcock cameo or a Castle introduction is a kind of guarantee to viewers that their cinematic “experience” will be not unlike those they have undergone in viewing previous Hitchcock and/or Castle films.

Diegetic Play and Authorial Self-Inscription

Castle seems to have recognized another important facet of Hitchcock’s cameos. Castle’s introductions, like Hitchcock’s cameos, merrily blur the line between the diegetic and the nondiegetic. When the bus door slams in the face of the portly man with the bass violin near the beginning of North by Northwest (1959), it is funny at the level of the diegesis, but the incident gains in value if we understand that the man is Alfred Hitchcock, the director of the film. It is a small moment of diegetic rupture, one of many such moments in Hitchcock’s career, and one of the pillars on which his authorship rests.

Castle’s introductory segments also blur the lines between the diegetic and the nondiegetic, and, in fact, do so in a far bolder manner than do Hitchcock’s cameos. When Hitchcock appears in his own films, he is recognizably Alfred Hitchcock, but he also plays a character within the diegesis: an unlucky bassist, a dog-walking pedestrian. Castle does not play a role in his films, and is not a part of his films’ diegeses, yet his introductions do have ramifications for his films’ narratives (fig. 5). He is our friendly compère, commenting on the story and setting its tone without ever assuming a role in the narrative proper. The quasidiegetic nature of these introductions provides an important clue: Castle will stake his claim to authorship on a strange and occasionally subtle – and even sophisticated – blurring of the boundaries of the diegesis. If we look for instance at two of Castle’s most intriguing films, The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960), there are surprising links between the seemingly separate introductions and the narratives proper.

For instance, although Castle himself does not reappear in the films, he sets up clear links between his non-diegetic persona and certain main characters in the films: Cyrus Zorba in 13 Ghosts and Warren Chapin in The Tingler (note the monogrammatic link). Furthermore, both figures and objects from the non-diegetic space of the introductions find their way into the narratives proper. In The Tingler the three screaming faces that we see in the introduction (see fig. 14) reappear as characters later in the film, and in 13 Ghosts Cyrus Zorba’s office resembles the office from which Castle delivers his prologue, featuring what may well be some of the very same “macabre” props: the skeleton and the skull (compare figures 6 and 7). That these elements overlap may be a result of the films’ small budgets, which necessitated the reuse of actors, sets, props, costumes, and the like. But something else is going on here. The blurring of the diegesis that results from the reuse of actors, props and sets, might safely be deemed coincidental were it not for further, more plainly deliberate occurrences in the two films – as well as other such occurrences in other William Castle films.

13 Ghosts

Castle’s manipulation of the boundaries of the diegetic space is a strong and distinctive authorial signature, one that is uniquely his. In the following I will focus first on the transitions from Castle’s introductions to the narratives proper in The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960) before expanding my observations to examples that involve large-scale diegetic blurring.

The first image in the introduction to 13 Ghosts (1960) (and in the film itself) is a medium shot of a door, through the frosted glass of which is visible the silhouette of a skeleton, which “opens” the door using a skull-shaped doorknob (fig. 8). William Castle’s name is printed on the glass in a “blood-dripping” font. “Come in,” a spooky, echo-drenched voiceover intones. “William Castle, the producer of this motion picture, has a question for you.” An axial cut through the now-open door reveals Castle sitting at a desk, on which rest a human skull and various flasks of the mad-scientist variety. He puts down a book titled “13 Ghosts” and, speaking to the camera, asks, “Do you believe in ghosts?” Coming out from behind the desk, Castle assures us that, by the end of the film, we will believe in ghosts, just as he does. He then turns to the skeleton, which rests in a nearby chair, and says, “No more dictation today.” The skeleton waves its pencil-clutching hand in a gesture of understanding.

Castle refers to the “special ghost viewer” handed out to all patrons, and proceeds to inform us how it works. Glancing heavenward, Castle says, “Would you please change the color of the screen?” An instant later, the image receives a blue tint reminiscent of the color used to denote “night” in many a silent film. Castle explains that, when the images in the movie turn bluish, we are to look through the red part of the viewer if we believe in ghosts, or through the blue part if we do not believe in ghosts (fig. 9). “Would you please change the color again?” Castle asks, again looking upward. When the screen returns to its standard black-and-while, Castle adds, “Oh – one more thing”: please inform any latecomers how to use the ghost viewer, if you’d be so kind. He then repeats the “red if you believe, blue if you don’t” instructions, and, after an axial cut back, says, rather stiltedly, “Happy haunting. Goodbye for now,” bows to the still-seated skeleton, and asks of it, “Shall we go?” The pair vanish from the room by means of the cut-rate “magic” of a hidden edit, whisked away by strains of dramatic, string-heavy music.

The funny thing is that the practical information Castle conveys in this three-shot, two-minute introduction is wholly unnecessary. The ghost viewer is a simple device whose function is immediately obvious: its two tinted lenses could serve no other function but to be looked through (fig. 10). Moreover, the viewers’ cardboard frames were printed with instructions on how to use the devices. All audience members – even latecomers – would not only have known about the existence and function of the ghost viewers, which were a key part of the film’s promotional strategies, and doubtless would have been able to figure out what to do with them by reading the instructions and/or glancing at their seatmates in the cinema.

The main function of this introduction, it seems, is to assert, reassert, and overassert Castle’s claim to authorship of 13 Ghosts. This claim may be made in a jocular spirit, but it is nevertheless forceful and unmissable: The first image we see is a door on which is written Castle’s name; the first thing we hear is a reference to “William Castle, the producer of this motion picture.” An instant later, we see Castle himself, clutching the “book of the film” – he figuratively holds the whole film in his hands (though, curiously, the book’s “author” is not Castle but screenwriter Robb White). Castle also demonstrates his power over the film by twice requesting that the color of the screen be changed, taking care to thank the unseen colorist on both occasions.

The introduction is also typical of Castle in the way that it occupies a kind of quasidiegetic space. It is separated from the narrative proper of 13 Ghosts by the fades in and out of black that bracket it; by the existence of the voiceover, which appears at no other time in the film; and by the very presence of Castle, who comments on the experience of viewing the film. Yet this introduction is also assuredly a part of the text known as 13 Ghosts and as the film proceeds, there are anaphoric references pointing back to the introduction. For instance, the narrative proper of 13 Ghosts begins with a fade-in to a brief establishing shot of the Los Angeles County Museum followed by a shot of the head and part of the torso of a dinosaur skeleton – an unexpected introduction to the interior space of the museum (fig. 11). The shot of the skeleton is arresting in itself, but also serves as a link to Castle’s introduction, in which the human skeleton is enlisted for two goofy gags. This associationalism on the notion of “skeleton” suggests connections between the space of the introduction and the space of the narrative. Both “worlds” prominently feature skeletons, and we are encouraged to consider the parallels between the introduction and the narrative proper (compare figures 6 and 11).

The playful use of the ‘skeleton’, though, is but an appetizer. Castle’s chief concern, at the level of both narrative and promotion, is a larger-scale diegetic blurring: the ability of the film’s characters and spectators alike to see the 13 ghosts in 13 Ghosts.

The premise of 13 Ghosts is that the Zorba family unexpectedly inherits a spooky old house from an eccentric uncle with the unlikely name of Dr. Plato Zorba. The house comes complete with hidden rooms, curious mechanical contraptions, and, of course, a passel of ghosts. The family suspects the house might be haunted, but receives no confirmation of the presence of supernatural beings until Cyrus stumbles across one of Dr. Zorba’s odd devices: a cumbersome metal-and-glass viewer that looks something like a welder’s protective eyewear (fig. 12). This viewer serves exactly the same purpose as the cardboard-and-plastic viewers distributed to audience members at screenings of 13 Ghosts: it allows the wearer to see ghosts. When the characters in the film put on the viewer, we are supposed to don our own viewers. The characters are our avatars – or, rather, we are theirs: their action of putting on the viewer determines that we do the same. We put on our viewers at the same occasions on which the characters put on their viewers, and for the same reasons that the characters do: to see the ghosts. Put another way, the act of wearing a ghost-viewer is integrated into the film, and thereby inserts the audience quite boldly into the diegesis of 13 Ghosts. We are both outside of the film and “inside” it at the same moment (fig. 13).

The boundary between the diegetic and the extradiegetic in 13 Ghosts is playfully porous. Furthermore, the blurrings of the diegesis are made with strong, obvious devices and gestures that call attention to themselves and winkingly bring the audience in on the joke. 13 Ghosts is not an isolated example of this tendency in Castle’s body of work. The Tingler (1959), almost certainly Castle’s best film, contains strong and clever occurrences of the same kinds of devices.

All A-Tingle

When Castle blurs or shatters the diegetic effect in The Tingler, his purposes seem to be twofold: to make strong claims for himself as an author, just as he does in 13 Ghosts; and to experiment with his own methods of film style and narration.

The Tingler opens with another of Castle’s introductions. In this one, Castle addresses the camera – and the audience – in a long shot from in front of a movie screen. “I am William Castle, the director of the motion picture you’re about to see,” he says, just before a somewhat awkward axial cut brings us in to a medium shot. In using this phrasing, Castle suggests that the introduction and the narrative proper are two distinct entities – a separation that the film itself soon challenges. The remainder of his introductory speech merits inclusion in full: |

|

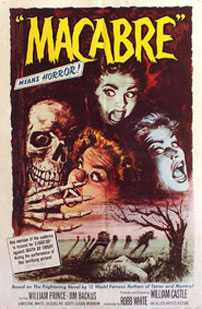

Fig. 2. Castle put forth a corollary, of sorts, of this attitude toward style in filmmaking in connection with his 1957 film Macabre: “[W]e’ll use good actors – actors that don’t look like actors – and if they happen to be stars, all well and good, but we’ll be hiring performers to fit parts, never altering parts to fit the players.” (Castle 1956, p. 26. Cited in Heffernan 2004, p. 97).

Fig. 3. William Castle’s authorship-asserting logo. “The public loved [my introduction to Homicidal],” Castle writes, “and as a result we became good friends. Kids would stop me on the street, calling me by name, asking for my autograph.” (Castle, p. 160).

Fig. 4. Hitchcock’s cameo appearances are also attractions in their own right – to be enjoyed for their cleverness or comic potential: missing the bus in North by Northwest, just after his own credit appears in the opening titles; walking the tiny dogs in The Birds; the clever weight-loss ad in Lifeboat (1944) illustrated above.

Fig. 5. In his early, pre-exploitation career (1943-58), Castle did often assume character roles. But as an exploitation filmmaker, he took a tiny part only in Shanks (1974), and audio-only roles in I Saw What You Did (1965) and Bug (1975). (He also had small parts in films he neither directed nor produced, both in 1975: Shampoo and The Day of the Locust.) Castle’s most noteworthy (and most Hitchcockian) cameo occurs in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), his only true “A-list” film as producer.

Fig. 6-7: 13 Ghosts: Castle’s office in the film’s introduction, and Cyrus Zorba’s office from the second scene of the film’s narrative. Though it would have been inaccessible to first-time viewers of the film in 1960, the shots of Castle in his office also contain a clever inside joke. On the walls are framed portraits – not of people per se, but of several of the thirteen titular ghosts that appear in later scenes of the film.

Fig. 8. 13 Ghosts: A skeletal secretary opens the door to William Castle’s office.

Fig. 9. 13 Ghosts: Castle demonstrates the ghost viewer. One of the film’s taglines was “You’ll believe in ghosts too when you see them through the new ‘ghost viewer.’ Free to everyone who sees this movie.” (Castle 1992, p. 162). Just in case we hadn’t gotten the message that William Castle is the author of 13 Ghosts, Castle himself returns in an epilogue to confirm that fact.

Fig. 10. The ghost viewer distributed to audiences of 13 Ghosts. The viewer seen here is not the same as the one that Castle displays in the film’s introduction, but appears to be authentic nonetheless. It is, for instance, identical to that displayed by the film’s ostensible star, child actor Charles Herbert, in a 1960 television ad for the film. Note that Castle’s authorship is confirmed on the viewer itself, in its reference to “William Castle’s 13 Ghosts.”

Fig. 11. 13 Ghosts: The first skeleton of the diegesis.

Fig. 12. 13 Ghosts: Cyrus wearing the ghost viewer.

Fig. 13. Another example of diegetic blurring in 13 Ghosts. As if the functionality of the ghost viewers wasn’t already sufficiently straightforward, the film itself, within its diegesis, provides clear, simple instructions for their use. Most modern (2010s) 3-D films invariably place their “put on your 3D glasses now” instructions before the narrative of the film begins, precisely so as not to interrupt it. |

|

| |

I feel obligated to warn you that some of the sensations, some of the physical reactions which the actors on the screen [here he smiles wryly and gestures at the screen behind him] will feel will also be experienced, for the first time in motion picture history, by certain members of this audience. I say “certain members” because some people are more sensitive to these mysterious, electronic impulses than others. These, uh, unfortunate sensitive people will at times feel [another wry smile] a strange, tingling sensation; others will feel it less strongly. [Here, another axial cut, now to a close-up.] But don’t be alarmed – you can protect yourself. At any time you are conscious of a tingling sensation, you may obtain immediate relief by screaming. Don’t be embarrassed about opening your mouth and letting rip with all you’ve got, because the person in the seat right next to you will probably be screaming, too. And remember this: a scream at the right time may save your life. (1)

At this point, the image fades to black and we hear a horrific scream. Far in the distance, a small, round, white light moves closer to the camera, soon dissolving into an image of the head of a screaming man. This effect happens twice more, until the screaming, terrified heads of two women appear in the same fashion, one on either side of the man’s head (fig. 14). Castle then brings us into the narrative portion of The Tingler by means of a graphic match – an associational technique that strongly resembles the use of the “skeleton” motif at the outset of 13 Ghosts; here, the association is on the notion of “screaming,” which Castle has already mentioned as central to the experience of watching The Tingler. The first screaming man’s head dissolves into a shot of the head of another man whose face also bears a look of abject terror, and for good reason: he is, we soon learn, a prisoner on death row, and is presently forcibly hauled by two guards down the hall to the electric chair, at which moment The Tingler’s opening titles begin (fig. 15).

The introduction is significant for several reasons. First, it establishes, in Castle’s gesture to the movie screen behind him, the notion of the “film within a film,” relevant to any understanding of The Tingler. In a key scene later in the film, Castle encourages us to conflate the screen on which we will soon see The Tingler with the movie screen featured within the diegesis of The Tingler.

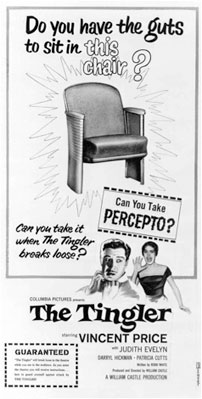

The “strange, tingling sensation” of which Castle speaks is a reference to “Percepto,” the one-of-a-kind gimmick that Castle devised for The Tingler, and probably the creation for which he is best known. Percepto was an elaborate system by which some of the seats in the theater showing The Tingler were rigged with electric “joy buzzers” that were activated by the projectionist at certain moments. Needless to say, Percepto was the centerpiece of Castle’s promotional strategies for the film (fig. 16). Castle’s choice of words here invokes the name of the film itself in a way that, again, blurs the line between the fictional (the story of The Tingler) and the actual (the “tingling” that will be felt by audience members). Indeed, as Castle effectively argues during the film’s key sequence, these two tinglings are one and the same.

The iconic heads of the three screaming people occupy a kind of non-space: they have no bodies, and they exist in a total blackness. But these actors are not strictly iconic, even as they exist, like Castle himself, in a kind of quasidiegetic space. Careful viewing reveals that the three people whose heads are isolated in this introduction also appear later in the film, in the most important scene of the narrative proper. The three actors play members of an audience watching D.W. Griffith’s Tol’able David (1921), the film within the film.

This key scene in The Tingler – the one on which all discussions of The Tingler must eventually focus – occurs near the end of the film. In the narrative of The Tingler, Dr. Warren Chapin (Vincent Price), a coroner, has been conducting experiments on people who have been “scared to death.” He hypothesizes that, at the moment of death by fear, a creature spontaneously appears along the human spine; it kills its host by constricting the vertebrae with its powerful muscles. Chapin further supposes that this lobsterlike creature, which he dubs “the Tingler,” can be neutralized when the host screams. In the diegesis of The Tingler, a scream can – and on several occasions does – literally save a human life.

Chapin at one point surgically removes a specimen of the Tingler from the spine of a deaf-mute woman. Since she cannot scream, she cannot release the tension inflicted by the Tingler, so she dies with the creature intact and alive inside her body. Later, that same Tingler pries itself out of a metal cage and finds its way into a repertory movie theater that, at the time, is showing Tol’able David (2). As the Tingler skitters along the theater floor, the piano accompaniment to Tol’able David increases in tempo and intensity, underscoring both the showdown between that film’s protagonist and antagonist and the threat posed by the Tingler; just before the creature first strikes, The Tingler’s own musical score blends with that of the piano accompaniment. The patron whose leg the Tingler first ascends is one of the two female screamers from the film’s introduction (her character’s date is the male screamer; the other female screamer is also visible in the audience); when she sees the creature, she shrieks, just as she did in the prologue, disarming the Tingler and causing it to drop to the floor.

After the women shrieks, the screen goes black – or, rather, the screens go black. Chapin rushes to shut off the theater’s lights, so that the patrons are plunged into darkness. At that same instant, the image track of The Tingler is replaced with a black screen, the better to replicate for viewers of The Tingler the conditions in the diegetic theater showing Tol’able David. Amidst the sounds of shuffling and general crowd confusion, we hear Vincent Price’s unmistakable voice: “Ladies and gentlemen, there is no cause for alarm. A young lady has fainted. She is being attended to by a doctor and is quite all right. So please remain seated. The movie will begin again right away. I repeat: there is no cause for alarm.” Having assuaged the crowd(s), Chapin turns the lights back on and Tol’able David recommences. |

|

(1) Kevin Heffernan wryly notes that Castle’s “certain members of this audience” clause is itself a wry reference to the fact that The Tingler’s distributor, Columbia Pictures, agreed to pay for the wiring of only one-tenth of theater seats. (Heffernan 2004, p. 100.)

Fig. 14. The Tingler: Three heads screaming in the dark. The man is Pat Colby, and the women are probably Gail Bonney and Amy Fields – all actors who played many bit and character roles from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Fig. 15. The Tingler: Dissolving from quasidiegetic to diegetic. The film’s final image is also, uncoincidentally, a close-up of the face of a screaming, terrified man who is about to be killed.

Fig. 16. A poster for The Tingler. I am fortunate enough to have seen this film “tingled” at New York’s Film Forum circa 1995. The same cinema tingled its seats once again for a Castle retrospective in 2010.

(2) Castle surely selected Tol’able David because he was able to acquire its rights for little money but in doing so also likens himself to D.W. Griffith, a filmmaker who has been incontrovertibly ensconced as an auteur. Indeed, both Griffith and Alfred Hitchcock, Castle’s two points of self-comparison, are more than auteurs – they are, to use Andrew Sarris’s phrase, “Pantheon Directors.” |

|

| |

But the Tingler’s work is not yet done. It creeps into the projection booth, where it interferes with the projector, causing its silhouette to be cast across the theater’s screen. (fig. 17). At this moment, as we watch The Tingler on our movie screen, the diegetic audience watches the Tingler on their movie screen; the perimeters of the two screens match precisely. Commotion ensues, and Chapin once again douses the lights and makes an announcement: “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not panic! But scream! Scream for your lives! The Tingler is loose in this theater, and if you don’t scream, it may kill you! Scream! Scream! Keep screaming! Scream for your lives!” After several seconds of the audience’s panicked dialogue and screams, Chapin announces, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Tingler has been paralyzed by your screaming. There is no more danger. We will now resume the showing of the movie.”

The moments at which the screen goes dark are the moments when the Percepto buzzers are activated. (Kevin Heffernan (2004, p. 98) notes that the Percepto system constitutes “what must be the ultimate direct audience address.”) Theaters screening The Tingler were expected to abide by other unusual arrangements at this key moment: a planted audience member would scream and “faint” at the same moment as the screaming woman in the film, the film’s projectionist would turn on the house lights as the image on screen cut abruptly to black, the soundtrack would be switched to emanate only from the rear speakers (which approximated Chapin’s position in the diegetic theater), and a pair of ushers would emerge to carry away the “unconscious” patron (ibid., p. 103). Castle’s intention was to synchronize the screams of the actors playing the patrons with the screams of the actual patrons, so shocked would they be by the unexpected vibration of their seats, as well as all the other commotion. While the on-screen patrons were menaced by the crawling Tingler, the actual patrons received an approximation of the effects thereof, via Percepto devices mounted to the bases of select seats. (For this reason, the film fairly begs to be seen under its original viewing conditions.) As nearly as possible, Castle replicates the viewing experience of the diegetic spectators for the spectators of The Tingler, just as he does in 13 Ghosts. The gesture calls attention to itself and to its author, the only one who could have come up with such a device. As well, this creative blending and blurring of two levels of viewing experience is in itself a clever use of film technique and a strong authorial gesture. |

|

[Fig. 17. The tingler on the screen on the screen of The Tingler.] |

|

| |

Since Castle was plainly interested in displaying boldly the marks of his authorship, it is reasonable to expect him to use other, equally “obvious” or “unusual” devices that foreground their artificiality for the purpose of encouraging, even prodding, us to take note of his cinematic craftsmanship. Indeed, in 13 Ghosts a diagonal splitscreen stands out - gaining in oddity for its singular use in the film (and for its compositionally privileged skull) (fig. 18) – as do a series of small but significant inside jokes that playfully break the diegesis. Take for instance the casting of Margaret Hamilton – best known, even in 1960, for her performance as The Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz – in a small but important role as a maid, Elaine Zacharaides. Elaine is a medium who in one scene leads a séance, and is often referred to by young Buck Zorba as a “witch.” In the film’s final scene, after Buck once again calls Elaine a witch and asks her if the ghosts will ever haunt his family again, Hamilton looks directly into the camera lens, actually grabs a broom, and exits the living room with a smirk. With such gestures, Castle invites us to play the game of the film, even if that means stepping outside of the conventional film/spectator relationship. |

|

Fig. 18. 13 Ghosts: The film’s sole split-screen shot. It separates Zorba from his wife, Hilda, with whom he is having a telephone conversation. |

|

| |

Similarly, The Tingler – a black-and-white film – contains a striking color sequence. This is a scene in which the deaf-mute woman – unknowingly terrorized by her husband, who wishes to frighten her to death – sees a red stream of blood flowing from her bathroom faucet, and a great pool of crimson blood filling her bathtub, from which a ghoulish, gore-soaked hand emerges (3). The blood is depicted in vivid red – it is the only thing in the room, and the scene, and the film that is not white, black, or gray. Though integrated into the narrative – the character is terrified by her visions, and we are seeing the room “through her eyes” – the effect is jarring enough to encourage us to remove ourselves from our engagement with the story and consider the “madeness” of the film (4). (It occurs at about 49 minutes into the film, by which point we have surely become accustomed to the film’s monochromatic palette.) In addition to the change from black-and-white to color, the scene in the bathroom, having been shot on film stock different from that used for the rest of the film, is strongly different in resolution: the quality of the images is much grainier than that of the great bulk of the movie. It is nearly impossible for even a casual viewer to fail to notice that this portion of the film has been made using a process quite different from that used to make the rest of the film. This crucial scene is both strongly integrated, in that we feel the character’s terror, and strongly distinct from the rest of the film by means of its visual qualities.

The blurring of the diegesis that Castle accomplishes in such unusual ways occurs most pronouncedly in The Tingler and 13 Ghosts, to be sure, but the device is also present to lesser degrees in several of his other exploitation films: to a limited extent in the overly expository introduction to House on Haunted Hill (1959); in the “Fright Break” in Homicidal, in which Castle’s voiceover intervenes near the film’s climax to let us know we have just a few seconds to flee the theater if we’re too scared; and in the “Punishment Poll” in Mr. Sardonicus (1961), in which Castle appears on the screen, in period costume appropriate to the film’s milieu, to inform us that we have the ability to vote for one of two endings for the film – strongly suggesting the more violent of the two – and even pretends to “see” our votes from “inside” the movie screen. Nevertheless, Castle’s use of diegetic play is inconsistent. It is not particularly relevant to Castle’s pre-exploitation career (although three of his earlier films were made in 3D, all of which are of the “hurl everything that isn’t bolted down directly at the camera lens” variety). And although Castle often engages in diegetic play in his exploitation films, he does not do so with perfect consistency. Castle’s use of diegetic play is an authorial signature that is thus unlike the well-known and highly consistent preoccupations of Hitchcock: voyeurism, falsely accused characters, unorthodox sexuality, careful point-of-view editing, “guilty women.” If Castle is so inconsistent, can he truly be deemed an auteur? Or is there room in authorship criticism for such wide variation?

The Bounds of Authorship

Another problem concerns Castle’s famous gimmicks. In some cases, such as 13 Ghosts, The Tingler, Mr. Sardonicus, Castle folds the gimmicks into the films themselves, granting them certain authority over narrative events. In others, such as Zotz! (1962), Macabre, and 13 Frightened Girls (1963), the gimmicks exist strictly at the level of extracinematic promotion. (In these cases, souvenir gold-colored coins, a life insurance policy against death by fright, and a nationwide talent contest for a part in the film, respectively.)

This raises a question that applies to Hitchcock as well as to Castle. Should authorship be applied as a relevant analytical framework if some of the marks of that presumptive authorship occur at the level of the extracinematic? Hitchcock’s unquestioned authorship depends in large part on extracinematic matters: not only the cameo appearances and introductions to the episodes of his television show “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” but even such devices as his droll sense of humor about matters macabre, his distinctive physical appearance and verbal delivery, and the graphical qualities of the well-known line-drawing of his profile. I would argue that these features – along with his cinematic signature of consistent thematic, narrative, and stylistic concerns – are of equal importance in defining Hitchcock’s authorial identity. But is it “fair” that Hitchcock’s authorship is unproblematically comprised of both cinematic and extracinematic elements, while Castle’s, which also depends heavily on extracinematic matters, is far less certain?

Do Castle’s gimmicks constitute sufficient grounds for his consideration as an author? The most sensible answer is surely no, for skill as a promoter is not the same thing as skill as a filmmaker. Were such a claim to be made, the next logical step would be to assert authorship for particularly talented P.R. agents, and that seems a slippery slope, indeed. Yet Castle poses a special challenge, in that all of the devices and techniques that may plausibly be considered evidence of his authorship – diegetic blurring and self-reflexivity, the inscription of himself into his films, gallows humor, perhaps even the very presence of the introductions themselves – are predicated, each and every one of them, on the gimmicks. Even the weaker gimmicks are more than mere bait for potential customers. They are the marks of the carefully constructed “William Castle” brand identity. Castle continued to employ gimmickry of some stripe until the end of his career, even though the gimmicks became less conceptually clever. That he sallied forth with the gimmicks suggests that Castle understood that the concepts of authorship and brand identity overlap to a great extent. Were it not for the gimmicks, Castle might not have had the opportunity to create an authorial style – if indeed he can be said to have done so.

If Castle does occupy one extreme position on the spectrum of gimmick-augmented authorship, Hitchcock would seem to occupy another. Hitchcock’s promotional acumen, gallows humor, and familiar public persona are all strongly determined elements of his authorial signature. Castle and Hitchcock are different in degree, but not in kind: they are both filmmakers whose styles are based, in part, on factors having little or nothing to do with their films themselves. Obviously, Hitchcock’s style is the stronger, richer, and more accomplished; more importantly, Hitchcock’s cinematic style is not dependent on his extracinematic excursions, as Castle’s surely is. I am not suggesting that these two filmmakers are equals. But the notion of the sliding scale of cinematic/extracinematic authorship is a useful one, in that it highlights the potential slippage between authorship and branding. Where does one stop and the other begin? Can they even be fully teased apart? If they cannot, what are the implications of considering them as parts of the same whole? |

|

(3) Castle’s method of accomplishing this unusual effect was quite clever. Though he used black-and-white film stock for all other scenes in the film, he used color stock for this one. The “blood,” in other words, was actually red, not colored in post-production. Everything else in the scene – clothing, walls, props, even the actor’s face and hair – was physically colored so as to appear on film as some value of gray. (See Heffernan 2004, p. 102.)

(4) It is not entirely clear whether this character, Martha, is, additionally, under the influence of LSD. The Tingler is well-known for being the first feature film in which a character (Chapin himself) undergoes an acid trip; the drug is introduced well before the color scene. Had her husband administered LSD to Martha without her knowledge, her hallucinations would be all the more justified and narrativized; as it is, though, the film leaves the question unanswered, so these may be garden-variety “visions,” or they may be the products of a bad trip, or both. |

|

| |

Auteurism: the Historical Perspective

Timothy Corrigan argues that it was during the 1960s and 1970s that the principal significance of auteurism shifted from the artistic to the commercial. In his essay “The Commerce of Auteurism: A Voice without Authority,” Corrigan makes a strong case for the “increasing importance … of the auteur as a commercial strategy for organizing audience reception, as a critical concept bound to distribution and marketing aims” (Corrigan 1990, p. 46) (5). The prime mover for the change in meaning of this critical concept is, unsurprisingly, economic. Corrigan attributes it to the film industry’s need to elevate cinema to the status of Art, the better to contrast it with “lower” forms of mass media, notably television. (An essentially Truffautian strategy!) “Despite its often overstated counter-cultural pretensions, auteurism became a deft move in establishing a model that would dominate and stabilize critical reception for at least thirty years” (ibid, p. 45). William Castle, then, in his use of authorship as a marketing tool, was part and parcel of a larger phenomenon – even though his particular brand of authorship is one without a great many counter-cultural pretensions.

Corrigan’s take on authorship is useful in considering the overlap between authorship and branding, but Castle’s films, it seems to me, present a special case, pushing past some of the chronological boundaries that Corrigan establishes. Corrigan writes,

[M]ore recent versions of auteurist positions have deviated from its textual center. In line with the marketing transformation of the auteur of the international art cinema into the cult of personality that defined the film artist of the seventies, auteurs have increasingly become situated along an extratextual path, in which their commercial status as auteurs is their chief function as auteurs: the auteur-star is meaningful primarily as a promotion or recovery of a movie or group of movies, frequently regardless of the filmic text itself. (Corrigan 1990, pp. 48-49)

All of which describes Castle’s strategies very well – but for the fact that he employed them in the late 1950s! Corrigan writes, “[I]f, in conjunction with the so-called international art cinema of the sixties and seventies, the auteur had been absorbed as a phantom presence within a text, he or she has rematerialized in the eighties as a commercial performance of the business of being an auteur” (ibid, p. 47; italics in original). Again, Corrigan’s description of the changing face of authorship would seem to incorporate quite perfectly the efforts of William Castle – right down to the remarkably apposite phrase “phantom presence” – yet, again, Castle (and, for that matter, Hitchcock) had blazed this trail at least two full decades before the turning point that Corrigan identifies. The paradigm shift in authorship seems inarguable; the unusual part about Castle is that he seems to have antedated it by many years.

Castle is also unusual in that he often makes, within his exploitation films, strong bids for his own authorship. Intriguingly, he makes his bids in fairly consistent ways from film to film. Can his cohesive, decade-spanning case for his own authorship be, in itself, one of the marks of that authorship? If authorship criticism is concerned with finding consistencies across a director’s body of work, then why wouldn’t this “count”? The fact that such an argument possesses a strange, reflexive logic is appropriate, given that Castle’s films are often highly (self-)reflexive in other ways, as well. And reflexivity, in its many forms, is itself a component of many authorial signatures – Hitchcock’s included.

For a filmmaker to make a claim for his or her own authorship – and for that claim to be repeated and confirmed by audiences, critics, and scholars; effectively “bought into” – is a process essentially identical to launching one’s own cinematic brand identity. While this may not have been the intent of the filmmaker/critics who initiated authorship criticism, it is not necessarily as troubling a notion as it may seem. Indeed, it is a realistic acknowledgment of the dual nature of cinema: artistic and commercial. Corrigan argues that the “auteurist marketing” of such name-above-the-title films as “Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900, David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter, or Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate guaranteed … a relationship between audience and movie whereby an intentional and authorial agency governs, as a kind of brand-name vision whose contextual meanings are already determined, the way a movie is seen and received” (Corrigan 1990, p. 45).

The discussion circles back, again and again, to the concept of branding, a notion that carries with it the unmistakable whiff of focus groups and manipulative public relations executives. But that same notion intersects with that of authorship in a curious, somewhat paradoxical way. In laying out a basic definition of the concept of branding, Michael Levine, in his book A Branded World: Adventures in Public Relations and the Creation of Superbrands, offers, first and foremost, “[Branding] is the creation and development of a specific identity for a company, product, commodity, group, or person” (Levine 2003, p. 3). A fairly general claim, to be sure, but the central concept – that of the specific identity – is one that, upon further scrutiny, bears a striking resemblance to that of the authorial signature. Literature on branding, in fact, often alludes or refers to concepts held dear by adherents to the ethos of the auteur. Levine’s book, for one, argues repeatedly that such concepts as uniqueness, consistency, specialization are essential to the development of any brand, including those that are rooted in a personality, not a product per se. Branding guru Peter Montoya’s how-to book The Brand Called You hits many of the same points, noting that differentiation is the single most important aspect of what the book capitalizes as Personal Branding; specifically highlighting consistency, noting that “your overall brand message – who you are, what you do, and how you provide value for your target market – must remain the same, so over time, prospects can become familiar with you”; Montoya even titles one of his chapters “Specialize or Sink” (Montaya 2002, p. 12, 39-40).

It takes only the smallest of leaps to locate these same jargonistic concepts within the doctrine of authorship. Uniqueness invokes a distinct and peculiar authorial signature; consistency would seem to refer to a director’s ability to apply that unique style across a larger body of work; and specialization invokes, among other things, the notion of a director making his or her mark in a particular genre of film, a concept not necessarily fundamental to authorship but certainly a frequent adjunct. All of which is to say that perhaps William Castle, in setting out to create a brand, created something like an authorial style – or, perhaps, vice versa.

The central irony here is that directorial branding is meant to ensure a certain level of quality, polish, and critical approval in the advertised films – yet these were the very ideas that François Truffaut railed against most passionately in his epochal diatribe “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema.” His well-known whipping boy, the mass of films that embody “The Tradition of Quality,” is precisely what an author-centric cinema was supposed to combat and destroy. Truffaut believed that French film had become a cinema of the screenwriter, and that, in order to assert its essential yet untapped artistic qualities, it must become a cinema of the director (see Truffaut 1954). And yet, in the advertising for any current given “name above the title” film, it is the inclusion of the name of the director that is implicitly intended to guarantee both “quality” and “artfulness.” The authorship ethos, which arose largely in opposition to certain notions of “quality,” is, today, commonly used to promote those same notions.

Authorship criticism started as a radical concept, fairly rapidly evolved into a theoretical and analytical framework, and is now perhaps most usefully understood a somewhat more vernacular concept that is based in part on popular consensus and in part on the ways in which directors create their own brands. Castle’s films expand the range of topics that authorship criticism, one of the most durable and useful analytical frameworks in film studies, may fruitfully address.

I would like to thank my colleague Vicky Semple and my friend Paul Ramaeker for making suggestions that helped me bring my arguments into focus. |

|

(5) Deb Verhoeven expresses similar ideas, and expands significantly on them, in her book Jane Campion (Routledge: London, 2009), particularly in Chapter Two. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

Literature

Castle, William (1956). “Castle Ideas Good Match with Ability,” Motion Picture Herald, March 24, 1956, p. 26.

Castle, William (1992). Step Right Up! I’m Gonna Scare the Pants off America: Memoirs of a B-Movie Mogul (New York: Pharos

Books).

Corrigan, Timothy (1990). “The Commerce of Auteurism: A Voice

without Authority,” New German Critique, No. 49 (Winter

1990), p. 46.

Heffernan, Kevin (2004). Ghouls, Gimmicks, and Gold: Horror Films and the American Movie Business, 1953-1958 [Durham, N.C.:

Duke University Press, 2004].)

Levine, Michael (2003). A Branded World: Adventures in Public Relations and the Creation of Superbrands (Hoboken, N.J.:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

Montoya, Peter, with Tim Vandehey (2002). The Brand Called You: The Ultimate Brand-Building and Business Development Handbook to Transform Anyone into an Indispensable Personal Brand (No place of publication listed: Personal Branding Press).

Sarris, Andrew (2001 [1962]). “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962” in Mast, Gerald; Cohen, Marshall; Braudy, Leo (ed.). Film Theory and Criticism, 4th edition (N.Y. & Oxford: Oxford

University Press). Reprinted from Film Culture (Winter 1962-

63).

Schaefer, Eric (1999). Bold! Daring! Shocking! True! A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University

Press).

Taves, Brian (1993). “The B Film: Hollywood’s Other Half,” in Tino

Balio, ed., Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Truffaut, François (1954). “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma No. 31; English

translation in Cahiers du Cinéma in English, No. 1.

Waters, John (2003). Crackpot: The Obsessions of John Waters (New

York: Scribner). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - juni 2011 - 9. årgang - nummer 42

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-11. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|