|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: It's not TV - or is it?

Af AUDUN ENGELSTAD

The Sopranos (1999-2007) and The Wire (2002-2008) have often been heralded as the zenith of television drama, and are regularly treated as if they transcend television all together. This position is not wholeheartedly embraced by academics, yet it is the uniqueness of the series that is often highlighted, thus glossing over how the series – as well as many other HBO drama series – truly belong to television as an art form.

If we look back on the past ten years, or perhaps even just the past five years, it seems fair to claim that the critical and academic interest in serial television drama, and in particular the notion of quality television, has peaked exceptionally. Today, television drama is a regular topic on the curriculum within film and media studies, but that was undeniably not the case only a few years ago. The change is partly due to the increased availability of DVD box sets, that allows for a concentrated (and repeated) viewing experience of critically acclaimed television series, as well as, and perhaps more importantly, the impact of a long list of impressive HBO drama series (also available on DVD, of course). The famed slogan “It’s not TV. It’s HBO” is foremost related to several much-admired drama series developed at the cable channel. Series such as The Sopranos, Deadwood, Six Feet Under, Carnivale, The Wire and Sex and the City have earned HBO a reputation as a quality brand, which then has worked back as a quality marker for the series. A HBO drama series is recognized as high quality, edgy, original – something that stands aside from everything else shown on television. Hence, it is not television, it is something else, something known as HBO.

The slogan is a clever marketing strategy but it invites to be taken seriously as well. Indeed, the slogan even features as a title, as well as the focal point, of a critical study dedicated to HBO (Leverette et al, 2008) (fig. 2). If taken at face value, what does the “Not TV” really imply? And what is gained by seeing the HBO drama series as something else than regular television? What are the merits of the HBO drama series that television otherwise do not hold? Has HBO become a venue for television drama that should be conceived as works of art rather than belonging to the sphere of television?

To Jane Feuer (2007), the HBO drama series are still indebted to television, but at the same time they lean heavily towards the traditions of art cinema and modernist theater, and she reminds us that this is something television drama has done before. Horace Newcomb (2007) is also convinced that a drama series such as The Sopranos should be regarded as television, and he situates HBO, and its slogan, within a post-network television era. It is television itself, rather than HBO, that no longer is television as we used to know it.

This article will bring forward some of the frequently addressed arguments in the discussion of quality television series, before giving attention to some lesser commented upon aspects of television that the HBO drama series inhabit, with The Sopranos and The Wire as the prime examples (fig. 3). Rather than belonging to what is considered high art, or illustrating a change in television programming, the aspects presented at the end of this article are among the foundational traits of television as a medium. They can be summed up by the keywords intimacy, dialogue and confession. The HBO television drama, it will be argued, though marked as different from most of the drama series screened on the network channels, are still operating within the main principles of how television works. As such, The Sopranos and The Wire, along with other HBO drama series – and by extension drama series from other cable channels, such as AMC and FX – are profoundly televisionesque.

TV vs. High Art

It is perhaps an outdated discussion, but there seems to be a repeated tendency to see quality and popular culture as two different and mutually exclusive entities. If a product of popular culture is endowed with an aura of quality, it ceases to exist as popular culture. Instead it moves to the realm of the art world. Historically, we can find this view expressed in W. H. Auden’s (1948: 151) classic article on the crime genre where he suggests that Raymond Chandler is not writing detective fiction, but rather serious studies of a criminal environment, and that his books “should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.” And Tzvetan Todorov (1977), in his famous article “The Typology of Detective Fiction”, claimed that any experiment with the established features of the genre, in order to improve upon them, implied a move towards serious literature. In line with arguments like these, popular culture and high art exist as two different systems – and never shall the twain meet.

Needless to say, this position has been challenged, in particular as a consequence of the interest postmodern theory has taken in popular culture. Jim Collins (1989) has demonstrated how crime fiction applies many of the strategies that define the writings within a modernist realm, such as a highly sophisticated play on intertextuality and the foregrounding of a self-conscious style. Indeed, much of the postmodernist aesthetics have been invested in blurring the boundaries between high and low culture, re-circulating tropes, forms, and narrative schemes established by popular culture. Apparently, postmodernism has put an end to the divide between the two art systems, it is all one mix now. Or so it seems at times, but perhaps it is not that easy.

The reason for bringing this issue up again, even though it is easy to get the impression that it is settled, is that the conflict between high and low appears to be embedded in the slogan that defines HBO as different from television. And much of the literature on quality television, a term that until recently was something like an oxymoron, is bent on drawing attention to traits like narrative complexity, character density, and a distinctly defined style – traits that otherwise belong to the field of high art. At the peak of postmodernism, by the late 1980s and early 1990s, television looked quite different from today. Perhaps this is the reason why the notion of artworks within television comes so belatedly to television studies.

The notion that the HBO television drama raises above the medium seems to be advocated by the series’ creators as well as HBO’s advertising department. Both writer-producer of The Sopranos, David Chase, and writer-producer of The Wire, David Simon, have in several interviews expressed a general lack of interest in television drama, and, it seems, in television altogether. Such a position is quite puzzling when looking at the track record of the two of them. It is obvious that they are well-seasoned within the trade of serial television drama. Chase has a background as a writer and a producer for television series such as The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. Originally, his ambitions for The Sopranos was for it to be a movie, and he has stated that he treated every single episode as an equivalent to a stand-alone film. Much can be said about such a claim, but it definitively works towards distinguishing The Sopranos as something other than ordinary television drama. As for Simon, he was a former crime reporter who was introduced to television as a writer and producer on Homicide: Life on the Street, based on his book Homocide: A Year on the Killing Street. As en executive producer and writer for The Wire he has made a point about bringing in creative people with little or no background in television. This, obviously, serves the impression that The Wire was conceived as unrelated to television. Both Chase and Simon, in their publically well-known statements, express a disdain towards television drama, what it is recognized by and what it achieves (see e.g. Biskind 2007 & Goldman 2006). |

|

Fig. 1. Is HBO’s slogan more than a clever marketing strategy?

Fig. 2. The slogan is not only the title of this book length study but also features in two articles (article one, article two) on HBO published in this journal.

Fig. 3. The Sopranos (1999-2007) as ‘high art’? |

|

| |

TV Auteurs

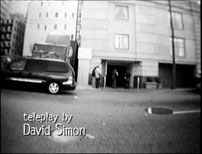

Whether or not Chase and Simon’s disdain for television is reasonable is beside the point. By their positions they – consciously, or not – apparently align themselves with the nouvelle vague filmmakers who revolted against the current state of French cinema and called for a politics of auteurs (fig. 4-5). If we follow this line of argument, Chase and Simon et al, do not necessarily express a desire to make something else than television – a film, a visualized novel, or something else – rather the goal is to make television drama into something other than what it is otherwise recognized as, yet still television drama. In other words, to explore and stretch the possibilities of television as an art form.

The idea of an auteur within television has been something of a contradiction in terms. The influence of auteur criticism arrived in USA in the 1960s at a time when cinema had lost the competition against television and found it necessary to distinguish itself from television. Ironically, some of the auteurs that came out of the period known as the Hollywood Renaissance had their background in television, such as Robert Altman, Bob Rafelson, Arthur Penn and John Cassavettes. Within cinema, the auteur is recognized as a person with a strong artistic impulse, the director who rises above the craftsmen on the film set, acting on an impulse to tell something of significance or of poetic value, and who is able to transform cinema to an art form worthy of serious debate. Television, on the other hand, is typically centered on personalities in front of the camera – the talk show host, the news anchor, the leading star of the soap series, and so forth. Take, say, The Late Show with David Letterman. The form follows a fairly strict format, and it really should make no difference who is doing the various jobs behind the camera. They are all replaceable. The only one that cannot be replaced without altering the show is David Letterman, the television personality. David Letterman can probably (and he once did) take his show to any other network channel, and it will still be recognized as The Late Show with David Letterman. The HBO drama series, by contrast, elevates the executive producer to the role of the artist. All though less pronounced, it is much the same position that Robert J. Thompson gives the producer in his study of quality television series of the 1980s and 1990s.

The Notion of Quality Television Drama

In his seminal book, Television’s Second Golden Age: From ‘Hill Street Blues’ to ‘ER’, Robert J. Thompson outlined a number of features constituting quality television drama, screened on American network television channels from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s. As his title indicates, he saw quality television drama inaugurated by Hill Street Blues, yet the phenomena of inventive television production had its predecessors. Television’s (first) golden age is generally identified as lasting from the mid 1940s to the late 1950s. The centerpiece of this period of inventive television was the anthology drama, such as Kraft Television Theater, Playhouse 90, and Actor’s Studio, broadcasted live on stage from Broadway (fig. 6-7). This was theater produced for television, applying three cameras for editing, and with an acting style that suited the intimacy of the format. The plays displayed a sharp social profile, with themes such as alcoholism, unemployment, and the disintegration of family structures, and it put dramatists such as Paddy Chayevsky and Reginal Rose on par with playwrights like Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller. No doubt, the proximity to Broadway and the real world of theater was beneficial in providing the anthology drama with an aura of quality. Although made for television, and acted for the benefit of the camera, the live anthology drama was experimental in a way that brought it closer to the theater than to television. Or, as Jane Feuer (2007: 147) has remarked, like today’s HBO, it was ’Not TV’.

In 1977, Roots, based on Alex Haley’s novel, aired as an eight-hour miniseries on consecutive nights. Roots demonstrated the long format’s advantage in handling a historical scope, showing the impact of various dramatic events on families and generations, witnessing personal stories as they develop over time. In addition, television proved able to treat a sensitive theme in a serious manner without reaching for the sentimental or sensational, at least not in a way that watered down the historical events. The historical miniseries earned its respectability by acquiring the qualities of the novel. It was serialized drama equipped with a memory, characters underwent change, relations altered along with the unfolding of the story. It is very much the complexities of narrative scope, the building as well as unveiling of the character’s back story, and the changing status the various characters inhabit, that have earned the HBO drama series – in particular The Wire but the others as well – the reputation of being visual novels.

With Hill Street Blues, as Thompson core argument goes, television series no longer drew upon other art forms, like theater or literature, as their key markers of quality. Hill Street Blues was most of all indebted to television itself. The ensemble cast, the cop show genre, serialized multiple storylines showing the characters’ work life as well as their personal life, were all household features on television. It was the combination that was new and it came along with the nervous style of cinema verité.

Thompson listed twelve characteristics of quality television series, the first being that it is best defined by what it is not: It is not regular television. What this means is that quality television series distinguishes itself from all the other television programs. Quality television drama usually has an ensemble cast, the story remembers past events, it often blends several genres in a new way, it tends to be writer-based rather than producer-driven, and it carries a distinct signature, often by someone with a strong footing in other art forms. Writing several years before The Sopranos and other HBO drama series, Thompson was remarkably right on target with his list of features.

Despite their bent towards originality, Thompson (1996: 16) suggests that quality television drama constitutes a genre on its own, “complete with its own set of formulaic characteristics […] that we normally associate with ‘good,’ ‘artsy,’ or ‘classy’”. Quality television drama is recognizable in its own way. To Thompson, quality television drama constitutes a genre by the same token that art cinema can be called a genre. Thompson’s study reminds us that when the HBO television drama series claims to be ‘not television’, or at least ‘as not seen on television before’, it is part of a long-running trend dating back to Hill Street Blues. And it is worth repeating that Hill Street Blues carried - above all - traits that were distinctly related to television.

Serialized Quality Drama and HBO

Jane Feuer gives an elaborate argument of how the HBO drama series, with Six Feet Under as her prime example, distinguishes itself from the quality drama of the 1980s and 1990s. Six Feet Under and HBO drama series in general draw upon soap opera just as quality drama does, by being serialized, they have an ensemble cast forming a workplace community or a family (or both), and they string the narrative together by multiple storylines. Yet, the HBO drama series, and Six Feet Under in particular, draw heavily upon a modernist cinema and avant-garde theater tradition, Feuer argues. As Feuer points out, this is not new to television, rather it stands in line with the live anthology drama of the golden age. Nevertheless, it makes the HBO drama series depart from what she refers to as prime time melodramas.

Feuer’s extensive writings on quality television and quality drama series are of course much more sophisticated than rendered here, and her untangling of the complex intertwining between primetime melodrama and quality drama is impressive as well as convincing. Still the discourse around quality drama (in general, and not necessarily with Feuer in mind) tends to be too preoccupied with discussing how these series are not television, or at least are different from other television series, at the cost of overlooking how many defining characteristics of the television medium actually permeate HBO drama series. The following will offer a brief discussion of how this can be seen played out in two of HBO’s crime series, The Sopranos and The Wire.

As Newcomb and Feuer, among others, have given elaborate accounts of, the HBO drama series have an ensemble cast that forms the community of the work place, or family, or sometimes both. In The Sopranos Tony (James Gandolfini) struggles to keep his professional family (the mob, his workplace) separate from his private family, and his ambitions seem to confirm Robert Warshow’s observation in his classic 1948 essay on the gangster as a tragic hero: becoming a respected member of society, or at least, in the case of Tony, a respectable member of the local community. Throughout the seasons of the show we witness how it is impossible to distinguish between the professional and the private families, as one affects the other in various ways. It is not only Tony’s two families that conflate in many complicated ways, this goes for several of the other members of the mob as well. Some of the storylines are foregrounded in a single episode, others are abruptly picked up at a later point, while still others drive the season’s story arc. The themes offered in The Sopranos might be existential, the events deeply felt, and the characters more profound than any soap can offer. But the story still unfolds in a manner intimately related to that of the serial soap.

The Wire is famed for its extremely dense narrative structure, but anyone who has watched several hundred hours of television drama (and many have), can enjoy watching only occasional episodes of the series. The ensemble is exceptionally large, but the members are divided by clearly defined work place environments (or its equivalent) that makes it relatively easy to sort out which strand of the narrative they belong to. Each season introduces a new work place that forms the core interest of the narrative – the Polish dockland workers, the school, the political office, the newspaper – in addition to the police force and the drug-lords. The narrative might be more complex and less redundant than seen on television before, but not different in principle. If The Wire ought to be compared with the great novels of Dickens and (perhaps even more fittingly) Balzac, it is equally fair to hold that the serial soap can be likened to the great narratives of the nineteenth century novel.

Intimacy, Dialogue and Confession

That the HBO drama series follow a serialized narrative format, and have an ensemble cast, is admittedly nothing new to the discussion. But there are other aspects to explore. As recent examples of “therapy drama”, In Treatment and Tell Me You Love Me (both HBO), highlight, intimacy, dialogue and confession are the core elements for staging drama – also on television. Indeed, these aspects can also be described as the founding principles of television as a medium. Although the therapy drama series come close to being a kind of de-dramatized television drama, and as such stands quite far from The Sopranos and The Wire, the latter still obey to the same principles that television of almost any kind is recognized by.

Intimacy. Television is the intimate medium par excellence. For one thing, television programs are composed in order to make the viewing situation in people homes as pleasurable as possible, and with the charismatic television personalities almost becoming something like a close family friend. Secondly, the intimacy is mimicked by the studio settings and the predominant use of close ups and medium close ups.

Neither The Sopranos nor The Wire can be said to offer intimacy in the first sense, with its depiction of brutal violence and heavy use of profane language. Yet, endless postings on discussion forums on the web bear witness to the fact that the viewers form strong relationships with the characters, however amoral and subversive they might be, and intense feelings of sorrow and emptiness occur when characters die or at the parting at the end of the series. |

|

Fig. 4. David Chase. TV auteur?

Fig. 5. David Simon. TV auteur?

Fig. 6. John Frankenheimer was the most prolific director of Playhouse 90 television dramas in the late 1950s. Other directors included Sidney Lumet and George Roy Hill.

Fig. 7. From the title sequence of The Wire (1st season, 2002). “Teleplay” echoes the term widely used for 1950s anthology dramas. |

|

| |

Also visually both series match an intimate style (fig. 8). The most extensive travelling sequence in The Sopranos is probably that of the opening credits. Otherwise, the setting is predominantly indoors; at Tony’s or someone else’s home, the office at the Bada Bing, inside Tony’s car, various hotel-rooms, and so on. We move outdoors as well, but we seldom move around outside. The Wire offers more out-door scenes, but the scenery is often quite compressed; the lot in front of the projects, the street-corner (rather than the street itself or the neighborhood), the prison yard, the dockland, in addition to numerous offices, bars, and inside cars. To be a story that folds out at a vast amount of places, it offers surprisingly little travelling between them. The Wire also offers a vide variety of full shots and long shots, much more than The Sopranos it seems, but not in order to give a feeling of a free and open space. The world is rather closed and claustrophobic (fig. 9).

Dialogue. If the idea of cinema is moving images with dialogue and sound added, the idea of television is dialogue and sound accompanied by images (both moving and static). Television’s closest kin in this respect is radio, not cinema. As a medium designed to be enjoyed at home, where all kinds of distractions take place, television is marked by redundancy. We are constantly told what we see, and important information is repeated in a multiple of ways; in discussions, in replays and recaps. Television is filled with talk, once the talk stop, a feeling of awkwardness and emptiness occurs. The talkshow is a quintessential television program, but also news, sport events and game shows are based on talk. This also goes for the soap opera, the hospital drama, the courtroom drama, as well as the cop show, which all are filled with endless expositional talk.

The Sopranos and The Wire might provide less expositional and redundant talk compared to the ordinary soap opera – or perhaps they are better at concealing the exposition in clever dialogue. Anyways, the characters talk all the time; these are dialogue-based dramas. The dialogue might be rapid-firing, overlapping, or even mumbling, in ways traditional television makes sure to avoid. Still, the dialogue is as essential to the HBO drama series as it is to the realist theater. For one thing it is a kind of stylized talk that works to give an impression of everyday language use (fig. 10). More importantly, it is the dialogue that defines the situation the characters are placed in.

Confession. The main purpose of all the talk on television, aside from its information value, is to unravel secrets and set the stage for confessions. Television is a therapeutic medium. Again, the talkshow is the prime example. Not only is it the preferred arena for politicians and celebrities to ‘come clean’ if they have been involved in a scandal. But the talkshow itself is centered on sharing intimate information about oneself. The celebrity talkshow, the confrontational talkshow, and the confessional talkshow are all centered on sharing awkward, aggravating, or shameful misdoings. This is also what soap opera is all about. The characters are constantly engaged in confessing their missteps, their grievance, their forbidden passions. A series like Six Feet Under even elevates this to a higher level, at times one gets the impression that every scene is structured around the making of a confession. Jane Feuer (2005: 35), with reference to the television series Once and Again and thirtysomething holds that: “All TV drama is confessional, and all quality TV deals with the psychology of the character”, and that thirtysomething, and by extension the HBO television series, do this in ways conversant with a modernist theater tradition. Compared to the prime time melodrama, the confessional moments seems less staged for the purpose in the HBO drama series, but it is still there to be enjoyed and witnessed without a preference of art cinema as a necessary given. (Perhaps what Feuer has in mind is that a series like Six Feet Under and a Bergman film like Autumn Sonata stage their confessional scenes in much the same manner. The point made in this present article, however, is that this does not command the interpretative skills otherwise related to art cinema.)

In The Sopranos the therapy session that opens the series demonstrates Tony’s inability to confess, but the audience learns all the secrets that is to know. Confessions are very much an underlying theme in the series (fig. 11). Carmela (Edie Falco) confesses her mixed emotions to the catholic priest, the gangsters have to express their loyalty and hope for forgiveness when they come clear with their mistaken actions. And Tony and Carmela perpetually confront each other with their shortcomings, spelling out their frustrations, making accusations, and revealing suppressed feelings.

The Wire might not offer confessions in a traditional sense, but there are plenty of moments of revelation, where the characters experience the consequences of their mistaken actions, and their secrets and missteps are exposed. Prime examples of narrative strands that carry strong confessional moments are the family relationships that the series explore, such as Frank Sobotka (Chris Bauer) and his son Ziggy (James Ransone), and D’Angelo Barksdale and his mother Brianna (Michael Hyatt), both in season 2 (fig. 12).

As crime dramas, neither The Sopranos nor The Wire hold a strong enigma that carries the plot. It is not a whodunit, not even a howdunit. There are no secrets to be answered. We might wonder what will become of Tony, but not so much what will happen next. In The Wire we might wonder if the criminals will be caught in the end, but how that might happen is of less interest. The Sopranos and The Wire can no doubt be said to be different from most other forms of television drama, not to say other television programs. Still, one should not believe that they appear on television almost as by accident, that they exist independently of the television medium (if anyone should believe that). The HBO drama series are in fact deeply rooted in the founding features of television. |

|

Fig. 8. An intimate moment in The Sopranos (1999-2007).

Fig. 9. The Wire (2002-2008). A shot from the low-rises in season 1: the series features many exterior shots but the characters are often ‘closed in’ by buildings. The windows of the tenants appear to look down at D’Angelo (Larry Gilliard Jr.) and his crew like a set of eyes: Someone is always watching… and listening.

Fig. 10. Stylized talk on The Wire: “’Snot Boogie’. He like the name?,” ask Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West) in the opening conversation of the first episode.

Fig. 11. A confessional moment in The Sopranos (1999-2007).

Fig. 12. D’Angelo tells his mother of a painful childhood incident in episode 6, season 2. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

References

Auden, W. H. (1948), “The Guilty Vicarage: Notes on the Detective Story, By an Addict.” In: Harper’s Magazine. May 1948.

Biskind, Peter (2007), “An American Family,” Vanity Fair (April 2007). [LINK: http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2007/04/sopranos200704]

Collins, Jim (1989), Uncommon Cultures: Popular Culture and Post-Modernism. London: Routledge.

Feuer, Jane (2005), “The Lack of Influence of thirtysomething.” In: Micheal Hammond and Lucy Mazdon, eds., The Contemporary Television Series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Feuer, Jane (2007), ”HBO and the Concept of Quality Television.” In: Janet McCabe and Kim Akass, eds., Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. London: I. B. Tauris.

Goldman, Eric (2006). “IGN Exclusive Interview: The Wire's David Simon” IGN, 27 October 2006. [LINK: http://tv.ign.com/articles/742/742350p1.html]

Leverette, Marc, Brian L. Ott and Cara Louise Buckley, eds. (2008), It’s Not TV: Watching HBO in the Post Television Era. London: Routledge.

Newcomb, Horace (2007),”’This Is Not AL Dente’: The Sopranos and the New Meaning of ’Television.’” In: Horace Newcomb, ed., Television: The Critical View, 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, Robert J. (1996), Television’s Second Golden Age: From Hill Street Blues to E.R. New York: Continuum.

Todorov, Tzvetan (1977), “The Typology of Detective Fiction.” In: The Poetics of Prose. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Warshow, Robert (1948). “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” in The Immediate Experience: Movies, Comics, Theatre, and Other Aspects of Popular Culture. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1962, pp. 85–88.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - februar 2011 - 9. årgang - nummer 40

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-11. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|