|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: The Art of Hunger: re-defining Third Cinema

Af NICOLA MARZANO

This article tries to address established notions of Third Cinema theory and its filmmakers from developing and post-colonial nations. The Third Cinema movement called for a politicized film-making practice in Africa, Asia and Latin America, since its first appearance during the 60’s and 70’s, taking on board issues of race, class, religion, and national integrity. The films investigated in this paper, from directors like Sembène, Getino, Solanas and Guzman, are amongst the most culturally significant and politically sophisticated from this movement and denote the adoption of an independent, often oppositional, stance towards commercial genres and mainstream cinema.

Third Cinema has posed – and continues to pose – difficult and challenging questions. These questions, then, are crucial to this article, an article that focuses on Third Cinema in an inclusive fashion, studying films from Argentina, Chile, Senegal, and even England. Suggesting new methodologies and subtle refinements of existing ones, this article aims at rereading the entire phenomenon of film-making in a fast-vanishing 'Third World'.

Coming to terms with Third Cinema

There is an endless debate about Third Cinema and its strategies in offering valuable tools for documenting social reality. From the 70’s onwards, appreciation of its value and aesthetics has been unfolded through controversial approaches and different views on this radical form of cinema.

The idea of Third Cinema was conceived in the 1960s as a set of radical manifestos and low-budget experimental movies by a group of Latin American filmmakers, who defined a ’cinema of opposition’ to Hollywood and European models. Possibly, this new form of expression came from three different areas of the world: Asia, Africa, and Latin America. At the time these three zones were labelled ‘Third World’ (sometimes they, or at least some of them, still are).

Even though scholars like Willemen explained how the notion of Third Cinema was most emphatically not Third World Cinema, these two concepts have often been confused either intentionally or accidentally (Willemen 1991: 3).

As an idea, Third Cinema came from the Cuban Revolution (1959) and the figure who supported this revolution – Che Guevara. Also the Brazilian Cinema Nôvo, where Glauber Rocha provided an uproar with his polemic manifesto titled The Aesthetics of Hunger (July 1965), was part and element of this new wave.

Some scholars, such as Michael Chanan, have suggested that some of the roots of Third Cinema could be traced back to Italian neo-realism and Grierson’s notion of social documentary, ultimately being influenced by Marxist aesthetics (Guneratne 2003:10). As investigated also by Willemen, filmmakers influenced by Latin American documentary include figures like Fernando Birri, Tomas Gutierrez Alea, and Julio Garcia Espinosa (Willemen 1991:5).

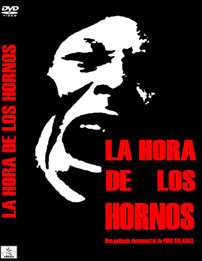

The term Third Cinema was invented by the Argentine film makers, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino who had produced and directed the most important documentary for the Third Cinema movement in the 1960’s, La Hora de los Hornos (1968, The Hour of Furnaces), at the same time producing an important essay sustaining the radical ideas of this movement: Towards a Third Cinema (Stam 2000:265).

In the words of Teshome Gabriel,

the principle characteristic of Third Cinema is really not so much where it is made, or even who makes it, but, rather, the ideology it espouses and the consciousness it displays. In one word we might not be far from the truth when we claim the Third Cinema (as) the cinema of the Third World which stands opposed to imperialism and class oppression in all their ramifications and manifestations. (Gabriel 1982:2).

From regional to global

Third Cinema has offered a significant means of documenting social reality through the analysis of documentaries from Argentina, Chile and Algeria and, on the other side of the Ocean, also from Black Independent documentaries.

A self-conscious, ideological opposition to Hollywood was the first marker of Third Cinema, while identification with national liberation was the second most common theme, at least in the early writings on the subject. The idea of “nation” in this discourse, however, is always at odds with a globalized Third World identification. On the one hand, the tri-continental definition of radical film aesthetics defies national boundaries. On the other hand, as Willemen notes, ”if any cinema is determinedly ‘national’ even ‘regional’ in its address and aspirations, it is Third Cinema.” (Willemen 1991:17).

The politico-cultural trends of the 1980’s and 1990’s have demonstrated the need for a definitive reappraisal of the terms in which a radical practice like Third Cinema had been conceived in the 70’s. Questions of gender and of cultural identity received new inflections, and traditional notions of class-determined identity were soon seen as inadequate.

The fathers of Third Cinema

The importance of Solanas’ and Getino’s work is due to both their manifesto about Third Cinema and the striking documentary of 1968, La Hora de los Hornos.

“Guerilla cinema”: La Hora de los Hornos

This documentary is important among revolutionary films for pushing the audience into action, hoping to subvert imperialism through the dynamics of its style and the radical and systematic ways in which it frames political and ideological issues.

By several authors this kind of cinema has been labelled ‘Guerrilla cinema’ or ‘cinema like a gun’ (Gabriel 1982:7)due to the force of their images and the violence with which the filmmakers address the socio-political issues of Latin America.

Through the use of montage, the whole documentary is divided into thirteen chapters and three sections. Each chapter is supported by statements, quotations and slogans.

At the time of its release, La Hora de los Hornos tried to unfold episodes and characters that, as stated by Gabriel, aimed to “raise the consciousness of its audience” (Gabriel 1982:25). La Hora de los Hornos represents a multi-layered form of documentary. The work is a combination of two or more modes of representing reality (and of facing social reality).

Defying categorization

In film theory documentaries are often divided into four (basic) modes of representation: the expository mode, the observational mode, the interactive mode and the reflexive mode (in Nichols’ Introduction to Documentary, however, two other representational modes are mentioned: the poetic and the performative modes (Nichols 2001, pp.99-138).

Though hardly impartial as observational documentarism (claims to be), the work of Solanas and Getino defiantly encompasses both expository, interactive and reflexive modes of documentary.

La Hora de los Hornos is divided into three sections: the first, ‘Neo-colonialism and Violence’, relates Argentina to the European influences; the second section, ‘An Act for Liberation’, explains the opposition struggle during Peron’s exile, while in the third section, ‘Violence and Liberation’, we can alternately appreciate documents, interviews and quotations framing the path to a revolutionary future for the people of Latin America.

This was the period, mind you, of the tri-continental revolution supported by figures like Frantz Fanon, Ernesto Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh. |

|

The Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas (Fig. 1,1) and Octavio Getino (Fig. 1,2) are central to Third Cinema, but the concept of Third Cinema is a global one, connecting a variety of different films from Africa, Latin America and even Europe.

The radical manifesto, The Aesthetics of Hunger (1965), by Glauber Rocha (Fig. 2,1) is often seen as the first manifestation of Third Cinema. In a film historical context, however, Rocha was presumably acquainted with and inspired by the critical writings of Cesare Zavattini (Fig. 2,2), a major proponent of Italian neo-realism.

The political documentary, La Hora de los Hornos (1968), by Solanas and Getino is often recognised as one of the most important works of Third Cinema.

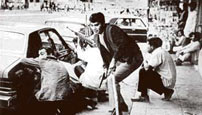

La Hora de los Hornos, made in 1968, is fittingly political and rebellious, and has even been described as “guerilla cinema”. Frame pair: La Hora de los Hornos. |

|

| |

Between minimalism and Brechtianism

The use of spoken and written commentary, directly addressing the audience, definitely embraced the notion of ‘Guerrilla Cinema’, where the spectator is called to act against imperialism.

From an editing point of view, recorded noise and distortive music play a discursive and demystifying role. Minimalism (or avant-garde)

is not only appropriate to the exigencies of film production in that particular context, but also reflects artistic strategies.

Third Cinema was trying to develop a new web of production and distribution, away from mainstream channels, and here La Hora de los Hornos avoided censorship by employing an underground system of distribution. Indeed, notes by Gabriel remind us of how sometimes the screenings of Solanas and Getino had to be protected by armed guards to avoid the risk of government retaliation (Gabriel 1982:126).

After its release, La Hora de los Hornos has been widely recognised – unquestionable in its value and importance – most likely because of its attempt to frame an ideological-political argument.

Radical treatments of actuality

The political strategies employed by the US in the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s, as described by the documentary of the two Argentine filmmakers, indeed are not too different from the strategies employed by the USA in the last few years of post-colonialism (during the reign of former President George W. Bush).

Unsurprisingly, without losing its force, La Hora de los Hornos could be screened to denounce the crisis that affected Argentina in 2000, due to economic struggles provoked by IMF and its bizarre financial strategies.

Solanas and Getino contributed greatly in building one of the most important columns and reasons for debate within Third Cinema (debates about notions like national culture and identity).

La Hora de los Hornos, as recognised by Robert Stam (Burton 1990:251), is probably the most influential documentary ever released in Latin America – not only useful as a tool for understanding the cultural and political discourses of the late 1960’s, but still meaningful as a tool for understanding actual social problems in Latin America.

Accordingly, in their manifesto, Towards a Third Cinema, Solanas and Getino stated the ideas and goals that were to be achieved through this movement:

The anti-imperialist struggle of the peoples of the Third World and of their equivalents inside the imperialist countries constitutes today the axis of the world revolution. Third cinema is, in our opinion, the cinema that recognises in that struggle the most gigantic cultural, scientific, and artistic manifestation of our time, the great possibility of constructing a liberated personality with each person as the starting point - in a word, the decolonisation of culture. (Stam 2000:269). |

|

Directly addressing the audience in an almost Brechtian fashion, La Hora de los Hornos is outspoken in its ideological critiques and messages. |

|

| |

Patricio Guzman

Many years later, in Latin America, another important documentary was released by Patricio Guzman - Salvador Allende (2004), a documentary which tells us about the life and death of the socialist president of Chile, who in 1973 was killed or pushed to commit suicide by both Pinochet and CIA in a coup d’etat (it is still debated whether he was killed or pushed to commit suicide, but there seems to be a general consensus on the latter).

As with The Battle of Chile (1977), a three-part documentary about Chilean socio-political life in the early 1970’s, Salvador Allende is an epic work, poised between direct and dramatized, immediate and mediated modes of describing historical events.

Both movies, through the use of a voice-over, mark the differences between these dramatic features and the concepts of direct cinema.

As underlined by Lopez,

although the sequence shots and the mobile framing, reframing, focus shifts, and movements within the image could code the film as “direct”, the voice-over reinscribes the filmic discourse as an authored discourse (Burton 1990:280).

Usually, Third Cinema has different channels of distribution compared to mainstream cinema. Therefore, often governments support this form of cinema, as was the case in countries like Cuba and Indonesia. Instead, in Guzman’s The Battle of Chile, Lopez reminded us how this documentary has never been shown under the rule of a dictator like Pinochet. |

|

Frame pair: Salvador Allende (2004) and The Battle of Chile (1977). |

|

| |

Third Cinema in Africa: past and present

In a continent like Africa, where film industries have long been struggling, the first point on a filmmaker’s agenda is looking for funds, and this need shows how Third Cinema’s struggle for survival is still harsh.

I will take into account, specifically, the period in which Third Cinema was born in Africa and particularly the works, Ceddo, Emitai and Cala by Ousmane Sembène.

Insiders and outsiders: Senegalese cinema

When one creates one does not think of the world; one thinks of his own country. It is, after all, the African who will ultimately bring change to Africa. (Ousmane Sembène, quoted in Gabriel 1982: 38)

Here Sembène, the Senegalese director, expresses not only his own particular philosophy, but also in a larger scale the project of Third Cinema, as it has been practiced in Africa.

Throughout his career, Sembène has encountered several problems with Senegalese censorship; usually his works have been either delayed or even forbidden.

Sembène has often portrayed Africa as a land consisting of different oppositional groups, each of whom fights for independence and cultural identity.

His film, Ceddo (1977), represents one of the most important pieces of Third Cinema in Africa. The title is, in itself, quite critical of the colonization process, its proper English translation being “outsider”.

This word, “Ceddo”, seems to portray and verbalize the struggle of ordinary Africans resisting a conversion to Islam and even Christianity.

According to Sembène,

The Ceddo is a lively mind or spirit, rich in the double meaning of words and knows the forbidden meanings. The Ceddo is innocent of sin and transgression. The Ceddo is jealous of his/her absolute liberty (Sembene, Gabriel 1982:87).

The film is set in a traditional African village during the period when North African Arabs were building Islamic colonies all over Africa. In the feature, the village included three symbols of foreignism which invade African spirituality: a European trader, a Catholic priest and an Arab Muslim. The movie shows the desire for colonizing African culture in all of these different characters (or icons), faced by the local “outsiders” (among which we find Ceddo).

For a long time African Third Cinema was also the cinema of silence, the silence witnessing an African spirituality that was to be protected and filmed without any form of invasion. Even though the first part of Sembène’s career was characterised by this element of silence as, featured in Emitai (1971), in Ceddo he has employed a different cinematic approach.

The silence in Third Cinema produced in Africa, and specifically by Sembène, seems to have two levels of meaning: Firstly, tradition is instinctual, and articulation is not necessary for active opposition to external religions. Secondly, the silence echoes a reverence for traditional culture, which, in spite of imperialist attempts to colonize the continent, remains deeply bounded to African identity. |

|

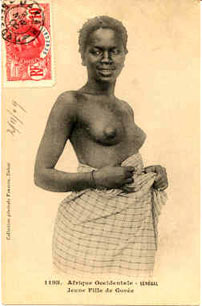

The director Ousmane Sembène has been recognised as the cinematic voice of Senegal, and his themes are often overtly and outspokenly Senegalese. |

|

| |

From Orientalism to African empowerment

Recently, a new form of Third Cinema, coming from the African continent, is that of video features.

According to Ukadike, it is useful to underline how almost all video films showing contemporary life and people in countries like Ghana and Nigeria are painted with an “ostentatious allure” (Guneratne 2003: 138). It seems the exotic representation of African culture, as seen through bare-breasted village women, has finally ended. Instead, we are beginning to see high profile, upper class people – especially businessmen and women.

Even if this new form of cinematic expression embraces a certain wealthy life style, at the same time these new video films, reminiscent of MTV, are filled with national heroes, local and famous songs. Their ways of portraying African countries and national identities are highly iconographic, and far from the supposed ethnocentrism of mainstream cinema in Hollywood and Europe.

Subsequently, these new forms embrace the strategies of Third Cinema, using different aesthetic devices – images, sound and music – to channel the struggle against past and contemporary forms of post-colonialism.

The debate among African filmmakers nowadays seems to be about the uniqueness of their cinema, often outspokenly different from European and American cinema. The aim pursued today by most of Third Cinema filmmakers in Africa lies in fighting the obstacles that are retarding the development of this continent, trying to find a common thread between post-colonialism, cinema and local identities.

Third Cinema within a European frame: Black Independents

Third Cinema includes a variety of subjects and styles, so this form of cinema can ideally be practised anywhere, opening the possibility of new formulations of Third Cinema also within Europe.

From this point view, we can analyse the importance of the Black Independents operating in the UK, this ”cinema of black diasporas” in itself being a new variation of Third Cinema.

The importance of Third Cinema as a medium produced also within European boundaries is raised by the position of the Black Audio Film Collective, formed in Britain in the 1980’s.

Despite their struggles in finding a new form of expression under Thatcherism, Black Audio Film Collective assumed a fundamental role in the presence of Third Cinema in a global reality much like today. Thus, talking about Third Cinema as a cinematic expression coming only from Latin America, Africa and Asia is, in fact, a way of dismissing the powerful impact that this movement has had, as well, in European countries.

Black diaspora is a relatively modern term used to describe the new ethnic groups that surface all over Europe – in cities like Paris, London, and Madrid. And why shouldn’t the realities of such ethnic groups, even as they are situated in European capitals, apply to Third Cinema? Couldn’t these be expressed in ways that are similar to the films of Solanas, Octavio and Sembène, focusing on similar themes and employing similar aesthetic choices?

As is noted by Auguiste, an interpreter of the Black Audio Film Collective, Third Cinema, in Britain, needed to find its own distinctiveness (Pines 1991:215).

Even though the filmmakers who represented Black Audio Film

Collective are working now as individual artists rather than members of the aforementioned collective, the importance of an alternative visual grammar is fundamental, still, to address the needs of this new generation. A generation of diasporas dealing with the same issues of de-marginalization as did their parents.

By supporting such groups of independent filmmakers, like the members of Black Audio Film Collective, it will be possible to redefine the borders and the tools of Third Cinema in these years of migration, globalization and diasporas. The multiplicity of identities and histories needs to be displayed through subjects able to read a dialogue between new technologies, class, gender and a mix of languages.

Third Cinema as ’third space’

Third Cinema may be conceived as a ‘third space’, a space displacing the histories and needs that constitute it and setting up new structures of identity and new political initiatives that cannot be adequately understood through mainstream cinema.

Due to a changing multiracial and multicultural reality, Third Cinema must reinvent itself in terms of gender, class and geographical identity – and consequently in terms of narrative structure and aesthetics.

The challenge between such cosmopolitan images and the struggle of local identity continues to move filmmakers. Looking for new ways to co-produce new Latin American, African and Asian cultural identities, the filmmakers work collaboratively with one ultimate goal: not a removal of the local, but a meaningful re-location of it in an ever-expanding global community.

Again, as with Solanas, Third Cinema needs to configurate itself as a cluster of different authorial icons. These icons representing their respective national cultures within a global market, without losing their status of oppositional figures to mainstream cinema or, even worse, losing their particular local identities.

As Robert Stam has poignantly noted, another important concept that may certainly re-launch Third Cinema is that of hybridity. Stam has emphasized how mixed cultures, like those in Brazil, Africa and Asia, are not just a ”property of the cultural objects portrayed but rather inheres in the film’s very process of nunciation, its mode of constituting itself as text.” (Guneratne 2003:43).

These concerns to define a necessary and new form of Third Cinema must not leave behind the primary concerns in the production of ‘revolutionary films’. The need of Third Cinema is undoubtedly a call for social and cultural transformation.

Even as historical contexts and aesthetic responses may change, its mandate to face post-colonialism and to protect local identities still holds. Obviously the present aim of Third Cinema, ignoring geographical borders, is to continue in seeking its own place in a global context. Third cinema is not the cinema of the Third World, but is the cinematic expression of the desire to express ourselves and our identities, although a general tendency of politics and culture is pushing towards a way of homologation and annulment. |

|

Ceddo (1977) is overtly different from classical images of Africa. As opposed to the orientalism so often connected with artistic renderings of Africa (fig. 8,1), Sembène’s movieis filled with haunting and deeply empoweringimages ofSenegal and Senegalese people (fig. 8,2).

Third Cinema is often misconceived as Third World Cinema. This type of radical independent cinema, however, needn’t be from ‘Third world’ countries. Even in Europe, directors and filmmaking collectives like Black Audio Film Collective make films that are associated with the principles and common practices of Third Cinema.

Through collectives like Black Audio Film Collective the concept of Third Cinema is constantly being re-invented. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Facts

Bibliography

Alberto E., Díaz López, M. 2006. The Cinema of Latin America. Wallflower Press, London.

Armes, Roy 1987. Third World Film Making and the West. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Barnard, Tim 1986. Argentine Cinema. Nightwood Editions, Toronto.

Burton, Julianne 1990. The Social Documentary in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh.

Downing, John D. H., 1987. Film and Politics in the Third World. Praeger, New York.

Gabriel, Teshome H. 1982. Third Cinema in Third World. UMI Research press, Michigan.

Guneratne A., Dissanayake W. 2003. Rethinking Third Cinema. Routledge, New York.

Karen, Alexander 2000. “Black British Cinema in the 90s: Going Going Gone” in Robert Murphy British Cinema of the 90s. BFI, London.

Loizos, Peter 1993. Innovation in ethnographic film. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

MacDonald K. Cousins M. 1996. Imagining Reality: The Faber Book of Documentary. Faber and Faber, London.

Martin, Michael T. 1995. Cinemas of the Black Diaspora: Diversity, Dependence, and Oppositionality. Wayne State University Press, Detroit.

Nichols, Bill 1991. Representing Reality. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Nichols, Bill. 2001. Introduction to Documentary. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Pines J. Willemen P. 1991. Questions of Third Cinema. BFI, London.

Rocha, Glauber 1995. “The Tricontinental Filmmaker: That Is Called the Dawn” in Johnson and Stam Brazilian Cinema, pp.76-80. Columbia University Press, New York.

Rosenthal, Alan 1988. New Challenges for Documentary. University of California Press, Los Angeles.

Renov, Michael 1993. Theorizing Documentary. Routledge, London.

Schnitzer, J&L. 1973. Cinema in Revolution – The Heroic Era of the Soviet Film. Secker & Warburg.

Stam, Robert, Toby Miller, 2000. Film and Theory: An Anthology. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford and Malden.

Swann, Paul 1989. The British Documentary Film Movement, 1926-1946. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Wayne, Mike 2001. Political Films: The Dialectics of Third Cinema. Pluto Press, London.

Filmography

Los Olvidados (Mexico, 1950)

Ultramar Films

Producer: Óscar Dancigers, Sergio Kogan, Jaime A. Menasce

Director: Luis Buñuel

B/W, 85 mins.

Terra em transe (Brazil, 1967)

Mapa Filmes

Producer: Glauber Rocha

Director: Glauber Rocha

B/W, 106 mins.

La Hora de los Hornos (Argentina, 1968)

Grupo Cine Liberacion, Solanas Productions

Producer: Fernando Solanas, EdgardoTallero

Director: Fernando Solanas, Octavio Getino

B/W, 260 mins.

Barravento (Brazil, 1969)

Iglu Filmes

Producer: Rex Schindler

Director: Glauber Rocha

B/W, 78 mins.

Emitai (Senegal, 1971)

Filmi Domirev

Producer: Ousmane Sembene

Director: Ousmane Sembene

Colour, 103 mins.

Xala (Senegal, 1974)

Films Domireew, Ste. Me. Production du Senegal

Producer: Paulin Vieyra

Director: Ousmane Sembene

Colour, 123 mins.

The Battle of Chile (Chile, 1977)

Equipe Tercer Ano Instituto Cubano de Arte e Industrias Cinematográficos

(ICAIC)

Producer: Chris Marker

Director: Patricio Guzman

B/W, 300 mins.

Ceddo (Senegal, 1977)

Films Domireew, Sembene

Producer: Ousmane Sembene

Director: Ousmane Sembene

Colour, 120 mins.

Handsworth Songs (UK, 1986)

Black Audio Film Collective

Producer: Lina Gopaul

Director: John Akomfrah

B/W, 61 mins.

Salvador Allende (Chile, 2004)

JBA Productions, Les Films de la Passerelle (co-production), CV Films (co-production), Mediapro (co-production), Universidad de Guadalajara (co-production), Patricio Guzmán Producciones S.L. (co-production), Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC) (participation), Canal+ (participation), Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) (participation), arte (participation), Yleisradio (YLE)

Producer: Jacques Bidou

Director: Patricio Guzman

B/W, Colour 100 mins. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - november 2009 - 7. årgang - nummer 34

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-09. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|