|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

16:9 in English: Given Circumstances: The East Asian Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, Part 1

Af BERT CARDULLO

The genius of Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) was manifold all through his long career, which he documented not only in images but also in words—namely, in interviews that I have collected in a book to be published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2008. The following is the first of two essays dedicated to the cinema of Kurosawa. It is an expansion of my introduction to the forthcoming Akira Kurosawa: Interviews and discusses the career and working methods of Kurosawa with particular emphasis on his reputation as a “Western” director. The second essay will be published in the subsequent issue of 16:9 and will focus on The Seven Samurai (1954)—a film that many consider Kurosawa’s greatest work as well as one of the great artworks of the twentieth century.

A Man For All Cinemas

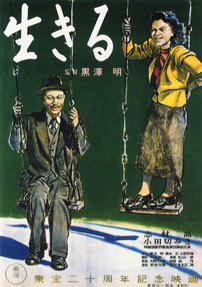

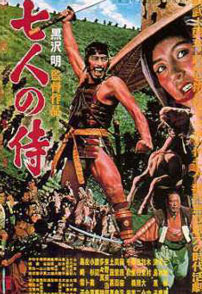

Prodigally, prodigiously, Kurosawa moved with ease and mastery and style from the most mysteriously interior to the most spectacular (fig. 1-2). Ikiru (1952) is about a dusty civil servant in postwar Japan doomed by cancer; The Seven Samurai is an historical epic about honor as a predestined anachronism. Contrasts from his filmography could be multiplied: Stray Dog (1949) is a crime-detection story; Kurosawa’s version of Dostoyevsky’s Idiot (1951) is so atypical in style that it’s hard to believe the film was made between Ikiru and Rashomon (1950)—itself a Pirandellian study, with somber overtones, on the relativity of truth or the impossibility of absolutes; and Record of a Living Being (1955) is about an old Japanese man who wants to migrate with his large family to Brazil to escape the next atomic war.

Indeed, Kurosawa could be called a man of all genres, all periods, and all places, bridging in his work the traditional and the modern, the old and the new, the cultures of the East and the West. His period dramas, for example, each have a contemporary significance, and, like his modern films, they are typified by a strong compassion for their characters, a deep but unsentimental, almost brusque humanism that mitigates the violence that surrounds them, and an abiding concern for the ambiguities of human existence. Perhaps most startling of Kurosawa’s achievements in a Japanese context, however, was his innate grasp of a storytelling technique that is not culture-bound, as well as his flair for adapting Western classical literature to the screen. No other Japanese director would have dared to set The Idiot, Gorky’s Lower Depths (1957), or Shakespeare’s Macbeth (Throne of Blood, 1957) and King Lear (Ran, 1985) in Japan (1).

But Kurosawa also adapted works from the Japanese Kabuki theater (Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, 1945) and used Noh staging techniques, as well as music, in both Throne of Blood and Kagemusha (1980). Indeed, he succeeded in adapting not only musical instrumentation from Noh theater but also Japanese popular songs, in addition to Western boleros and Beethoven (2). Like his counterparts and most admired models, Jean Renoir, John Ford, and Kenji Mizoguchi, he thus took his filmic inspirations from the full store of world cinema, literature, and music.

Kurosawa and the West

As for the suggestion, as a result, that Kurosawa was too “Western” to be a good Japanese director, he himself always insisted on his simultaneous Japanese and internationalist outlook. As he remarked in the Film Comment interview cited above, “I am a man who likes Sotatsu, Gyokudo, and Tessai in the same way as Van Gogh, Lautrec, and Rouault. I collect old Japanese lacquerware as well as antique French and Dutch glassware. In short, the Western and the Japanese could actually be said to live side by side in my mind, without the least sense of conflict.” To be sure, along with other Japanese directors and with Satyajit Ray (whose Pather Panchali introduced Indian cinema to the West in 1955), Kurosawa’s films share a liability to remoteness in Western eyes—in his case, not in style or subject matter but in the performative details of gesture and reaction. Yet his work is less affected by cultural distance than that of most Asian directors.

Hence it was not by accident that the first Japanese director to become known in the West was Akira Kurosawa, when Rashomon won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, together with a Special Oscar as best foreign-language picture of the same year. Up to then, although the Japanese film industry had been enormously active, with high annual production figures, it might as well have been situated on the moon as far as the West was concerned. World War II was not a prime reason for the gap; relatively few Japanese films had been seen in Europe and America before 1939. (When Rashomon opened in New York, it was the first Japanese film to be shown there since 1937.) The barrier to import was financial, not political—the same barrier that obstructs the import of foreign literature.

The cultural shock that followed from the Venice Festival showing of Rashomon was a smaller mirror image of the shock felt in Japan a century earlier when Commodore Perry dropped in for a visit. Then the Japanese had learned of a technological civilization about which they knew very little; now Westerners learned of a highly developed film art about which they knew even less. It was lucky that they learned of Japanese film art through Kurosawa, for he was not merely a good director. He was one of the cinema’s great masters, whose masterpiece, in this case, typically came from stimuli Eastern and Western: as he pointed out in a 1992 conversation with me, from the spirit of the “French avant-garde [silent] films of the 1920s,” as well as from Rashomon’s literary source, two short stories about medieval Japan by the twentieth-century Japanese author Ryunosuke Akutagawa.

Something Like a Biography

At the time Rashomon took the world by surprise, no one in the West could have known, of course, that Kurosawa was already a well-established director in his own country. Moreover, his career tells us something, prototypically, about the Japanese film world. He was born in Tokyo in 1910, the son of an army officer of samurai descent who became a teacher of physical education. Kurosawa, unattracted to his father’s professions, studied painting at the Doshusha School of Western Painting. (Note its name.) Then in 1936 he saw an advertisement by a film studio looking for assistant directors; applicants were asked to send in an essay on the basic defects of Japanese films and how to remedy them. He replied, and—together with five hundred others—he was invited to try out further, with a screen treatment and an oral examination. Kurosawa was hired and assigned to assist an experienced director named Kajiro Yamamoto.

The details of Kurosawa’s apprenticeship may be found in Something Like an Autobiography (1982). But what strikes an outsider is that a newcomer’s entry into Japanese film life, at least in those days, was organized and systematic—which is to say that the system of Japanese film training had adopted some of the tradition-conscious quality of Japanese culture generally. Kurosawa himself saw fate as well as chance at work in his choice of a career, as he revealed in Something Like an Autobiography:

It was chance that led me to walk along the road to P.C.L. [Photo

Chemical Laboratory, later absorbed into the Toho Motion Picture

Company, for which Kurosawa made thirteen films from 1943 to 1958],

and, in so doing, the road to becoming a film director, yet somehow

everything that I had done prior to that seemed to point to it as an

inevitability. I had dabbled eagerly in painting, literature, theater,

music, and other arts and stuffed my head full of all the things that

come together in the art of film. Yet I had never noticed that cinema

was the one field where I would be required to make full use of all

I had learned.

Yamamoto—himself a director of both low-budget comedies and vast war epics—soon recognized the younger man’s qualities, and did much to teach and advance him during their six years of collaboration. While Kurosawa gained experience in the chief technical and production aspects of filmmaking, the core of his training under Yamamoto’s guidance was in script-writing and editing. (In interviews, Kurosawa often quoted Yamamoto’s remark that “If you want to become a film director, first write scripts.”) Thus was born a true auteur, who edited or closely supervised the editing of all his films and wrote or collaborated on the scripts of most of them (in addition to writing screenplays for the films of others, beginning in 1941 for Toho and ending in 1985 with Andrei Konchalovsky’s Runaway Train). |

|

Akira Kurosawa.

Fig. 1-2. These two posters for Ikiru and Seven Samurai illustrate the great spectrum of Kurosawa’s cinema.

(1) The intercultural influence has been reciprocated: Rashomon directly inspired the American remake titled The Outrage (1964); The Seven Samurai was openly imitated in the Hollywood movie called The Magnificent Seven (1960); the Italian “spaghetti Western” A Fistful of Dollars (1964) was pirated from Yojimbo (1961); and Star Wars (1977) was derived from The Hidden Fortress (1958).

(2) Kurosawa told Dan Yakir in 1980, in an interview published in Film Comment, that his generation and the ones to follow grew up on music that was more Western in quality than Japanese, with the paradoxical result that their own native music can sound artificially exotic to contemporary Japanese audiences. |

|

| |

Something Like a Filmography

That auteur made his first film, Sanshiro Sugata, in 1943, when he was thirty-three (fig. 3). Though in a 1964 interview in Sight and Sound he judged this picture to be a simple entertainment piece concerned with the judo tradition, the visual treatment of its story, through composition and montage, is innovative and exuberant. Clearly this was the work of an individual talent, even if, in Kurosawa’s own estimation—as he explained to Donald Richie in the Sight and Sound interview—he finally discovered himself as a director only in 1948 with Drunken Angel (fig. 4). By 1950, with the completion of Rashomon and his début in the West, he had made eleven films.

During the whole of his career, which ended in 1993 with Madadayo, Kurosawa made thirty motion pictures, alternating between or even combining the two principal categories in Japanese cinema: the gendai-mono, or drama of modern life, and the jidai-geki, or historical drama. As Kurosawa discussed with me in “A Visit with the Sensei of the Cinema,” Rashomon’s story and setting fall into the category of jidai-geki, but his approach to the story does not conform to the characteristics of costume drama, action adventure, or romantic period-piece common to this genre. Through the use of several fragmentary and unreliable narratives, Rashomon in fact is modern and inventive in its telling. Whereas Drunken Angel, which belongs to the genre of gendai-mono, has a traditional or conventional narrative, even if it does treat contemporary social issues connected with the fate of postwar Japan.

Part of the impact of these two films, of all of Kurosawa’s films, derives from the typical Japanese practice of using the same crew or “group” on each production. Kurosawa consistently worked with the cinematographers Takao Saito and Asakazu Nakai; the composers Fumio Hayasaka and Masaru Sato; the screenwriters Keinosuke Uegusa, Shinobu Hashimoto, and Ryuzo Kikushima; and with the art director Yoshiro Muraki. This “group” became a kind of family that extended to actors as well. Mifune and Takashi Shimura were the most prominent names of the virtual private repertory company that, through lifetime studio contracts, could survive protracted months of production on a film for the perfectionist Kurosawa by filling in, in between, with more normal four-to-eight-week shoots for other directors. Kurosawa was thus assured of getting the performance he wanted every time. Moreover, his own studio contract and consistent box-office record enabled him, until relatively late in his career, to exercise creativity never permitted lesser talents in Japan—creativity made possible by ever-increasing budgets and extended production schedules, and which included Kurosawa’s never being subjected to a project that was not of his own initiation and writing.

Such creative freedom allowed him to experiment, and one result was technical innovation. Kurosawa pioneered, for example, the use of long or extreme telephoto lenses and multiple cameras in the final battle scenes, in driving rain and splashing mud, of The Seven Samurai. He introduced the use of widescreen shooting to Japan with the samurai movie Hidden Fortress, and further experimented with long lenses on the set of Red Beard (1965). A firm believer in the importance of motion-picture science, Kurosawa was also the first to use Panavision and multi-track Dolby sound in Japan, in Kagemusha. Finally, he did breathtaking work in his first color film, Dodeskaden (1970), where the ground of a shantytown on top of a garbage dump turned a variety of colors—from the naturalistic to shades of expressionism and surrealism—as a result of its reaction with chemicals in the soil (fig. 5).

As a result of the artistic control that made possible such technical innovativeness, together with his ever-expanding international reputation, Kurosawa got the epithet “Tenno,” or “Emperor,” conferred on him. But this epithet amounts less to any autocratic manner or regal raging on Kurosawa’s part than to a popularized, reductive caricature of the film director at work. Among his peers, including Lindsay Anderson, Peter Brook, and Andrei Tarkovsky as well as the Americans Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas, Kurosawa was a sensei of the medium, a respected mentor on the set as well as off it.

And nothing reveals the reason for this respect more than his approach to screenwriting. Since his earliest films Kurosawa had preferred not to write alone, because of the danger of one-sidedness in interpreting a major character. So, with his “team,” he always retired to a hotel or a house isolated from distractions; sitting around a table, each one wrote, then took and rewrote the others’ work. Afterwards they talked about what they had created and decided what to use. This was the first stage in an essentially collaborative process—the next stage of which was the careful rehearsing with the cast and the camera crew before any filming could take place. |

|

Fig. 3. Although Kurosawa reputedly directed some scenes in Uma (1941) it is Sanshiro Sugata (1943) that marks his directorial debut proper.

Billedtekst: Fig. 4. Drunken Angel represented his first collaboration with the actor Toshiro Mifune, who was to become a frequent protagonist in Kurosawa’s oeuvre.

Fig. 5. An image from Kurosawa’s first color film Dodeskaden (1970). |

|

| |

The above facts, titles, dates, and statements—though certainly relevant—nonetheless do not convey the shape and quality of Kurosawa’s career. Like other giants in film history, he seemed to grasp every possible contributory element in his own make-up, along with the core of this (relatively) new art, and mold them all to his needs, his wants, his discoveries, his troublings. To see a retrospective of his work, which I have done twice nearly completely, from the beginnings through Drunken Angel and Rashomon and Ikiru and The Seven Samurai to Red Beard and Kagemusha and Ran, is consequently to see that, like every genius, Kurosawa invented his art. Of course his work can be analyzed, and analysis can enlighten, but it can’t finally explain the result of the coalescence of all those elements, the transmutation that made him unique, imperial (3).

Mozart himself dedicated six quartets to Haydn, from whom he had learned, but what he learned was more about being Mozart. What Kurosawa learned from his teacher Kamamoto was more about being Kurosawa, which is to use action like hues on a canvas, shaded or enriched; to establish characters swiftly; to have a sure eye for pictures that are lovely in themselves yet always advance or augment the story, never delay or diminish it; to transform the screen before us into different shapes and depths and rivers of force, with stillness and with blaze; to make life seem to occur, but, like a true artist, to do this by showing less than would occur in real life. To be Kurosawa was also to use light and air subtly; to help your actors into the very breath of their characters; to create an environment through which a narrative can run like a stream through a landscape; to know infallibly where your camera ought to be looking and how to get it there; to create a paradoxically spare richness that grows out of dramatic juxtaposition, unforced yet forceful grouping, and a persistently following camera, rather than out of laid-on sumptuousness in detail or color. |

|

(3) Hence Kurosawa’s imperious complaint of critical over-determination in a conversation with Joan Mellen published in her Voices From the Japanese Cinema (1975): “I have felt that my works are more nuanced and complex, and the critics—especially the Japanese ones—have analyzed them too simplistically.” |

|

| |

Indeed, the very motion of Kurosawa’s motion pictures is gratifying, particularly the complementary deployment of two fields of motion—that of the camera and the actors. This does something that only film can achieve: an unaffected yet affecting ballet in which the spectator, through the moving camera, himself participates. Kurosawa has long been celebrated for such camera movement, in the form of tracking shots (fig. 6-7). Prime examples: the woodcutter striding into the forest in Rashomon; the opening ride of “Macbeth” and “Banquo” in Throne of Blood; in Kagemusha, the many, many tracking shots of furiously galloping riders, flags aflutter, the sweep of which is marvelous since Kurosawa sometimes blends one shot into another going a different way.

Often the motion in this film and Ran is made by men only, with the camera still, as the men are hurled across our vision in strong, startling patterns. Soldiers will pour down from (say) the upper right corner of the screen diagonally while another stream moves from the middle of the lefthand edge and bends away as it meets the opposition. Such a vista turns the engagement of armies rolling away over hills into a terrible excitement. Occasionally, the pulse of motion is carried by one man alone among many still ones: early in Kagemusha, for example, a messenger runs frantically through an encamped army, through loafing and sleeping soldiers, bearing a message to his lord. As he plunges ahead, the men he passes come awake or start up, and in this simple strophe—the messenger’s feet pounding past the resting or sleeping men—is a whole conviction of being in an army at war, with the lulls and starts of service.

Even when Kurosawa’s subjects seemed slight for his abilities, as in The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963), there runs through most of his work a conviction of mastery that is itself exciting. It is not cinematic magic of the kind to be found in later Fellini, nor is it Angst made visible as in the best of Bergman; instead there is an unadorned fierceness to Kurosawa’s style, steely-fingered and sure. The many beauties for the eye seem the by-product—inevitable but still a byproduct—of this fierceness and the burning, ironic view behind it. Indeed, what flames in many of his films, contemporary and costume, is hatred. In Ikiru it is hatred of death, but in most of them it is hatred of dishonor. Like most ironists and most intelligent users of melodrama, Kurosawa was thus an idealist in deliberately thin disguise.

Asked in 1966, in an interview in Cahiers du cinéma, whether he considered himself a realist or a romantic, he corroborated my view by replying, “I am at heart a sentimentalist” (my translation from the French). So much so that, upon accepting the 1990 Academy Award for life achievement at the age of eighty, Kurosawa could remark, without false humility, that the honor came too early in his career, for he was still in the learning stages of his art. “Only through further work in cinema,” he explained, “will I ever be able to come to a full understanding of this wonderful art form.” |

|

Fig. 6-7. Tracking shots follow the woodcutter striding into the forest in Rashomon. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Fakta

Bibliography

Cardullo, Bert. “‘I Am Simply a Maker of Films’: A Visit with the Sensei of the Cinema (1992).”

In Akira Kurosawa: Interviews. Ed. Bert Cardullo. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi,

forthcoming in 2008.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like an Autobiography. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1982.

Mellen, Joan. “Interview with Akira Kurosawa.” In Mellen’s Voices From the Japanese Cinema (New York: Liveright, 1975), pp. 43-58.

Mellen, Joan; Mellen, Josn. The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan through Its Cinema. New York: Pantheon, 1976.

Richie, Donald. Kurosawa Interview. Sight and Sound, 33, #3 (Summer 1964), pp.

108-113; 33, #4 (Autumn 1964), pp. 200-203.

Shirai, Yoshio; Shibata, Hayao; Yamada, Koichi. “’L’Empereur’: entretien avec Kurosawa

Akira.” Cahiers du cinéma no. 182 (September 1966), pp. 34-42.

Yakir, Dan. “The Warrior Returns: Akira Kurosawa Interviewed.” Film Comment 16, 6 (Nov.-Dec. 1980), pp. 54-57.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16:9 - juni 2007 - 5. årgang - nummer 22

Udgives med støtte fra Det Danske Filminstitut samt Kulturministeriets bevilling til almenkulturelle tidsskrifter.

ISSN: 1603-5194. Copyright © 2002-07. Alle rettigheder reserveret. |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|