|

Impressions of Violence, Moments of Witness Each assassination sequence may be broken down into four segments, as indicated in Table I, which correspond to each other in their depiction of similar events: Table I – Assassination Sequences, Segment Duration and Number of Shots

For the most part, the segment durations also match quite closely. The opening segments are exceptions to this, but relatively speaking, segments I.1. and II.1 remain the longest segments in their respective sequences. Each of the opening segments, the Business of Crime and the Business of Play, is emblematic of one of the film’s two storylines, and concludes its development. Taken together, they also typify the tension between the pursuit of the burdens of work or duty that Kitano’s characters are saddled with, and the pursuit of the pleasures of play. It’s a tension characteristic of many of Kitano’s films, one which is often (though not always) resolved for the protagonists in an unpleasant manner. (Sonatine could be said to represent its tragic mode, Kitano’s later Kikujiro, its comedic.) |

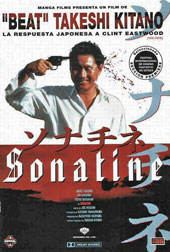

Sonatine (1993). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The more immediate function of these two segments is to reiterate a stability immediately prior to its disruption. Segment I.1 refocuses the film on the initial crime plot, depicts Murakawa’s ineffectuality in resolving the Okinawa situation (to the extent of removing him from the scene entirely), and presents the first fruit of Takahashi (Kenichi Yajima), Murakawa’s duplicitous compatriot, and their boss Kitajima’s plan to betray Murakawa and Nakamatsu. The segment also provides a visual link to Takahashi and the scenes in Tokyo: in his initial appearances, Takahashi wore a tie decorated with vividly green vegetation and bright red flowers (fig.1); here, the meeting takes place alongside a country road that winds through a field of tall, dense, green vegetation, studded with red flowers (fig.2). A similar color motif appeared in the restaurant backroom where Kitajima disparaged Nakamatsu, disingenuously reassured Murakawa of their solidarity, and, together with Takahashi, attempted to convince Murakawa to accept the assignment (fig.3). The roadside meeting place in I.1 thus comes to represent the perhaps inevitable outcome of the earlier scenes. Segment II.1 presents a scene of play, typical of those depicted throughout the Okinawa scenes, (and typical as well of similar scenes in Kitano’s other films). Miyuki (Aya Kokumai) observes from the sidelines, and Katagiri (Ren Osugi), who rarely participates in Murakawa’s games, is absent. Murakawa shoots at a red frisbee, then gives Ken a chance to shoot (fig.4). It recalls the film’s first play scenes, where Ken and Ryoji (Masanobu Katsumara) first tried to shoot cans off of each others’ heads, William Tell style, and then were forced by Murakawa to play Russian roulette. The segment also foregrounds the two couples of the film, Murakawa and Miyuki, and Ken and Ryoji, whose relationships have developed over the course of the Okinawa scenes. And as Katagiri assumed the role of Murakawa’s surrogate in the criminal realm in segment I.1, here, Ken acts as a momentary surrogate in the realm of play. Segments I.1 and II.1 thus offer a summing up of the events and two opposed subjects of the film’s narrative. The correspondence between the other segments, in terms of narrative events, is more readily apparent. In I.2 and II.2, Takahashi’s hit man performs an assassination (of Nakamatsu, of Ken). In I.3 and II.3, those who have survived stand (or sit) in mute witness to the assassinations. In I.4 and II.4, the film moves away from the Assassination and the Moment of Witness into Aftermath. I.4 depicts the hit man’s progress through the woods towards the beach, (site of his next assassination); and in II.4, Murakawa’s final, lonely, failed attempt at play on the beach, tossing the frisbee to himself while his four surviving companions look on. In both four part assassination sequences, Kitano offers moments of relative stability (an apparent resolution to the yakuza narrative; yet another day at the beach in the play narrative) immediately prior to the violation of that stability, a set up for the violent punch line that follows. Getting Down to Business |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Segment II.1, by contrast, cuts more rapidly, opening with a pair of 3 second shots: the moving image of the red frisbee, followed by second shot of Murakawa shooting at the frisbee as it flies by. This is then followed by a 5 second, medium two shot of Miyuki and Ken laughing at Murakawa. The remainder of the segment follows a more conventional editing pattern, employing consistent eye-line matches between those seated by the derelict boat, and those playing with the frisbee. Facial expressions are regularly visible, and the middle angle at which the camera is set produces compositions that ensure a separation between the characters and the landscape (fig. 5-6). Unlike the first segment of Sequence I, then, which holds the viewer at a distance from the characters, the first seven shots of Sequence II enfold the viewer into a dynamic space, one which encourages an identification with characters engaged in acts of play. This in turn corresponds to the location of each respective storyline within the film’s syuzhet: the crime narrative still remains distant, largely offscreen, sketched out by dialogue; the narrative of play, on the other hand, continues to occupy the attention of both Murakawa and the viewer, and continues to hold a central, privileged position in the syuzhet, as it has for the past thirty-five or so minutes. Here, we get a sense of the potential modularity of Kitano’s approach. He can string together any number of such moments, according to them greater or lesser degrees of narrative import, and different emotional timbres. This in turn leads to a degree of episodicness within the framework of a goal-driven narrative that otherwise corresponds in its construction to the four large-scale parts, marked out by “[shifts] in protagonist’s goals,” that Kristin Thompson has identified as characteristic of classical and neo-classical narratives (27). This might be seen as a further manifestation of the tension between work and play in Kitano’s films. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Making an Impression This moment of stability and relative ease is disrupted by the middle segments, those of the Assassination and the Moment of Witness. The assassination of Nakamatsu takes place after an elliptical cut from the static, high angle shot of the meeting place (fig.2). Suddenly, the viewer is confronted with an extremely frontal, slow motion, 14 second medium shot of Nakamatsu before a wall of green vines, facing the camera, away from his mistress. He is flanked by his two henchmen, who were still leaning against the cars on the of the road at the end of the previous shot. All three men stare directly into the camera. After a moment, first one henchman, and then the other is shot, falling out of frame as they die (fig.7). Nakamatsu is himself shot and killed, leaving behind a frame filled only by smoke, green vines, and red flowers. The suddenness of this shot, its momentarily unmotivated nature, and the graphic disruption that it wreaks on the previous shot provides a moment of intense shock, further enhanced by the fact that this is the first killing we have seen since Murakawa shot Miyuki’s rapist his first night in Okinawa, and the first gang-related killing since the bar shootout that drove Murakawa into hiding. Here, the crime narrative begins its movement back to the center of the syuzhet. Alternately, one could say that this is the moment that the goals of Takahashi and Kitajima wrest control of the narrative. |

Fig.7 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The severity of this disruption is amplified by the sequence that follows, the Moment of Witness, (I.3), in which we see the hit man, back to the camera, already walking away from the scene, a brief return to the overt graphicality as the mistress surveys the bodies (fig.8), and then a second shot of the hit man, further down the trail. These low key, de-dramatized shots are overwhelmed by the shock of the assassination shot, even as they move the viewer away from that moment of violence. Something similar occurs in the second assassination sequence: again the segments are separated by a somewhat elliptical cut: segment II.1 concludes with an extreme long shot of Murakawa, Miyuki, Ken, and Ryoji on the beach, the hit man visible at the far right of frame (fig.9). The camera then cuts to a closer long shot, from behind the derelict boat, of Ken and Ryuji. The frisbee flies over Ken’s head, past the camera. He turns, and runs to get it, but stops short, staring at something off camera (fig.10). The next shot reveals the hit man, who has, with apparent speed and stealth moved down the beach and behind the boat (fig.11). Again, there is a sudden shock (fig.12). Both assassinations exhibit Kitano’s characteristic approach to violence, one that he described in an interview:

Unlike the first assassination, however, the second is divided into 7 short close up and medium shots, 1 to 2 seconds in length, that cut back and forth between Ken, the hit man, Ryuji, and Murakawa and Miyuki, safely hidden by the boat. Where Nakamatu’s assassination is drawn out in slow motion, a primarily visual spectacle, Ken’s assassination is rendered a more emotional spectacle, as before the actual shooting, the viewer is given the chance, if briefly, to register not only Ken’s reaction, but the reactions of his friends, and the odd, dispassionate expression of the man who kills him (fig.13-15). And unlike the first assassination, which generated a sudden if drawn out shock, this segment overlays its shock with a brief but intense moment of dread, as we wait, with Ken, for the hit man to pull the trigger. As in the first segment of this second sequence, we are encouraged by the film to more closely identify with the characters, enfolded into their psychological space, as we had been enfolded into their physical space earlier in the sequence. This continues into the sequence’s Moment of Witness, as we are granted clear views of Murakawa and Miyuki’s faces (contrast fig.16 with fig.8), and into the sequence’s Aftermath, as the narrative remains at the scene of the assassination rather than departing from it. In both sequences, as is so often the case in Kitano’s films, the staging of violence is not enough. There must be witnesses as well, characters whose forward motion, through the narrative, through their lives, is stopped short by a sudden, decisive moment of violence. The witnesses are the ones within the diegesis who receive the impression of violence, and their positions both within the narrative and within the staging of the scene inform the audience’s own impression of that moment of rupture. “It’s Over.”The Aftermath segments share a similar function, closing off each sequence, steering the narrative onward. I.4 links the first assassination to the second, carrying the hit man from the meeting place to Murakawa’s beach, in a shot (fig.17) that recalls an earlier extreme long shot of Murakawa and friends walking along the beach with the red frisbee. He stops at a pile of red flowers, the sequence concludes with a dissolve from a low angle shot of the flowers tossed in the air by the hit man, vivid against the clear blue sky, to the first shot of the second sequence, a low angle shot of the red frisbee sailing by. II.4, meanwhile, assigns the blame for the assassinations, (Katagiri: “It’s over for Takahashi.”), and points towards the events of the film’s climax, (Katagiri: “He’s [Murakawa] ready to go all the way.”), and more immediately, towards Murakawa, Katagiri, and Uyeji’s attempt to kidnap Takahashi in the sequence that follows. At the same time, however, the Aftermath segments perform different functions. I.4 primarily serves to generate suspense, ushering the hit man into the same space and time occupied by Murakawa and his companions. He represents a reassertion of the crime storyline, a forceful and ultimately dominating reentry of that storyline into the narrative. The music that plays over the first assassination sequence reinforces this. It begins as a faint, repetitious, tentative yet energetic drumming as Katagiri and Uyeji arrive at the meeting site. Over the course of the scene, the rhythms of the drumming become increasingly complex. As Nakamatsu reveals that the Anan want his clan to disband, and that he plans to retire because his mistress is having his baby, an oddly joyful melody joins the drumming. Over the remainder of the sequence, the music continues, energetic, upbeat, unswerving. Upon a second viewing of the sequence, the drums seem to mimic the buoyant, springing step of the hit man, its growing volume and increasing complexity marking his imminent approach to the meeting site. After Nakamatsu’s assassination, it carries him toward his next target and its cessation at the end of the first sequence, and replacement by the sound of insects, wind, and surf lend a tension to the first scenes of that sequence, prompting to viewer to await the hit man’s reappearance, to expect the other shoe to drop. This intrusion of the crime narrative into the narrative of play is also marked by the dissolve from the red flowers, tossed in the air, to the frisbee: the spectacle of redness, associated with blood, and thus with the hit man, hover over the scenes of play in the next sequence, in keeping with an observation made by Daisuke Miyao. Tracing out the interplay of red and blue in Kitano’s films, Miyao suggests that red functions in Sonatine as “a symptom of violence and characters’ death,” as well as “an object of attraction or obsession for the protagonist” (119). Thus, those characters who wear red clothing, (such as Ken), and those who obsess after red objects, (as Murakawa seems to in the Aftermath of the second sequence, tossing the red frisbee into the air again and again), are inevitably marked for death (Miyao: 120). This could potentially invite to too restrictive a reading, however: Ryuji, who briefly dons a red robe, survives the film; Uyeji, killed during the kidnapping of Takahashi, never wears red; and Murakawa’s seeming obsession with the red frisbee at the end of the second assassination may have another explanation (120). It should be noted that Miyao does try to avoid assigning to color an overly schematic function within the stylistic systems of Kitano’s films. And as quoted by Miyao, Kitano himself seems reluctant to assign particular meanings to red, to the so-called “Kitano blue,” or to other colors. Kitano does note, however, that he likes to “use blue as [his] base color,” and offers the following explanation:

This may provide another way of understanding Kitano’s characteristic depiction of violence, and his overall construction of narrative: the relatively static nature of many of his compositions, and the long, uneventful stretches that appear in many of his films may work to provide an unassuming narrative base, analogous to that provided by blue for the other colors in the films, against which brief moments of violence more starkly “pop out.” |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rather than displaying Murakawa’s obsession with death, the second Aftermath segment instead conveys Murakawa’s sense of loss over Ken’s death. (Perhaps a subtle distinction from Miyao’s reading, but a significant one, I think.) The shots of Murakawa playing with the frisbee (fig.18) further extend the compositional motif, developed over the course of the Okinawa beach segment, of extreme long shots of play on the beach. At the same time, these new shots modify that motif. They present a single person rather than a group, engaged not in an act of play, but in a reenactment of the memory of play, an act of mourning. Where the earlier group shots had suggested, through their extreme camera distance, the idyllic distance that Murakawa and his companions had placed between themselves and the world of the yakuza, and their mutual enjoyment of that idyll, these shots register a profound loneliness. |

Fig.18 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The depths of this loneliness, and the severity of Murakawa’s sense of loss, are further underlined by the juxtaposition of these shots with the medium shots of Miyuki, Katagiri, Uyeji, and Ryoji (fig. 19). Most obviously, this juxtaposition marks out Murakawa’s isolation from both the group, and from the small, safe world he has constructed in and around the beach house. This is further modified by the arrangement of the characters within the frame: Ryoji, Ken’s counterpart and constant companion in play, stands closest to the camera, eyes cast down, echoing Murakawa’s sense of loss; furthest from the camera stands Miyuki, her body nearly blocked from view by Katagiri, just as Murakawa’s chances for romance have been eclipsed; and side by side, on either side of the center of the frame, stand Katagiri and Murakawa, uniform figures, standing tall in grey and white shirts, framed by Ryoji and Miyuki. Both men look down at Murakawa, as if beckoning him back to the violent yakuza life he had hoped to set aside. Ken’s death is unique in the film. No other death receives this same treatment. No other death is so carefully drawn out for the viewer. And no other death generates the same reaction in the film’s characters. More precisely, no other death induces the same reaction in Murakawa. In the next to last shot of the segment, (fig.20-21), Murakawa tosses the frisbee straight up. It does not reappear. Ken’s parting is complete. And the film begins its inexorable movement towards its bloody climax, and equally bloody epilogue. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|