|

|

| Up Close and Impersonal:

Hal Hartley and the Persistence of Tradition Af DAVID BORDWELL In run-through histories of English-language film studies (do we need so many?), at least one chapter casts Screen in a starring role. The British Film Institute quarterly, we are told, was largely responsible for introducing semiotics, Lacanian and Althusserian theory, and other post-Structuralist tendencies into the Anglo-American conversation. During the same years, however, a much less-discussed journal was at least as important. Edited by Thomas Elsaesser, Monogram was no less ambitious than Screen, as its first issue in spring of 1971 made clear. The new magazine would carry on the line of inquiry that the editors had launched in The Brighton Film Review. It would "investigate the main cinematic tradition as we see it, and to define at least one possible approach to the cinema as a whole, by a careful attention to the actual films being made today, whether commmercial or independent, and to re-assess outstanding or interesting works of the past."[1] Tradition? One possible approach (and not the approach we must take)? Re-assess (that is, make explicit value judgements, and on artistic grounds)? In 1971 this enterprise probably seemed far too cautious. The tradition referred to was, unapologetically, that of Hollywood, then being widely condemned as ideologically oppressive. In France, Cinéthique and Cahiers du cinéma had forged a radical perspective during 1969-1970, and Screen was about to publish Christopher Williams' essay presenting Godard as "an important link between the American-dominated cinema of the past and the politicized cinema of the future."[2] As if in anticipation, the Monogram editorial continued: "We are not a theoretical magazine, nor are we persuaded that a particular political commitment will necessarily dispose of, or resolve, certain fundamental aesthetic problems."[3] The waiver is too modest (many Monogram essays were deeply theoretical), but the emphasis is clear. Aesthetics still mattered, and the problems it posed were to be tackled in ways different from Screen's version of High Theory. Yet the journal would also avoid the main alternative, that Leavisian attachment to moral, not to say moralizing, psychological realism most visible in the work of Robin Wood. "The cinema," the editorial asserts,"derives its complexity and richness not only from its relation to felt and experienced 'life' a difficult quality to assess at best - but also from the internal relation to the development and history of the medium."[4] Monogram would steer a new course between Parisian theory and Cambridge Great Tradition realism. As a methodological first step, its writers would posit that the history of Hollywood cinema - "classical cinema," as the editorial calls it - is central to any adequate account of how films in many traditions tell stories. These views, controversial to this day, seem to me still well-founded. I can scarcely imagine my own conceptions of film research without the powerful essays published across the five or so years of Monogram' s life. In particular, the idea that we may analyze any instance of cinematic expression in relation to formal and stylistic traditions has been a guiding premise for me, and I owe to Monogram, and particularly Thomas Elsaesser, not only this cogent formulation but also many well-formed examples. In the thirty-some years since Monogram's editorial, Elsaesser has never forgotten how culture and politics shape cinema, but he has also preserved his zest for the manifold ways in which the medium can be used artfully. Monogram's contributions to our understanding of the Hollywood tradition were extensive and insightful. Perhaps the most celebrated piece in the magazine's history is Elsaesser's intricate, erudite essay on melodrama, which soon became a cornerstone in the study of that genre. Just as important, Monogram's emphasis on "actual films being made today" acknowledges that our knowledge of cinema's past can inform our understanding of our contemporaries. Thus in the journal's second issue, Elsaesser offered a wide-ranging reflection on the current state of European cinema. His insights into then-current films by Bu˝uel, Bergman, and Godard proceeded from a detailed knowledge of the directors' cultural positions and an easy familiarity with their directorial signatures.[5] Faithful to the Monogram premise, his approach was comparative, looking for ways in which the filmmakers had taken up or taken apart the conventions of classical cinema. This comparative approach informed many subsequent essays in the journal, notably the studies on the "Cinema of Irony" (issue 5) and Elsaesser's fine "Notes on the Unmotivated Hero" in then-current US cinema.[6] And Elsaesser's unflagging concern with understanding the present in terms of its past drives many of his writings over the years; to take only a few examples, his work on Wenders, his essay on Bram Stoker's Dracula, and his magisterial volume on Fassbinder. The enduring influence of classical style, the fruitfulness of a comparative method, and the need to make sense of contemporary cinema - these precepts triangulate my efforts in what follows. If Hal Hartley had been making films in the 1970s, or if Monogram were still publishing, it seems likely that the two would have intersected, perhaps around concepts like the unmotivated hero or the perils of irony. What I hope to show by looking more closely at one Hartley film, Simple Men (1992), is that analysis sensitive to the avatars of tradition can still shed light on the formal changes and continuities on display in contemporary cinema. Hartley belongs to the more formally adventurous wing of the US indie scene, a quality perhaps most evident in his storytelling strategies. He brings a low-key absurdity to romantic comedy (The Unbelievable Truth, 1989) and melodrama (Trust, 1990).[7] He has experimented with plot structure as well, most notably in the almost gimmicky three-episode repetitions of Flirt (1996). Hartley is also one of the most idiosyncratic visual stylists in contemporary US film. Yet every innovator draws upon some prior traditions, and Hartley is no exception. The actors' eccentrically flat readings of soul-bearing dialogue, for example, are evidently his reworking of the neutrality he finds in Bresson's players. At the pictorial level, several broad trends seem to have provided models and schemas which Hartley has creatively recast. Perhaps least obvious is the group style dominating Hollywood since the 1960s, a style I've called elsewhere "intensified continuity." The label seeks to capture the fact that although American mainstream directors haven't rejected traditional continuity filmmaking (analytical cutting, 180-degree staging and shooting, shot/ reverse-shot, matches on movement, etc.), they have modified it by heightening certain features. They have made shot lengths, on average, shorter. They have amplified the differences between long-lens shots and wide-angle ones. They have increased the number of camera movements, particularly tracks in to and out from the players and circular movements around them. And they have employed more and tighter close-ups than were typical before the 1960s. Many of these options may be traceable to the fact that the television monitor is the ultimate venue for most films, but there are probably other causes at work as well.[8] Most indie films adopt the idiom of Intensified Continuity, but Hartley's style assimilates it prudently. He does not favor fast cutting: compared to the 3-6 second average shot length which became dominant in Hollywood during the 1990s, his shots run, on average, twice or three times as long.[9] He does employ long lenses to pin figures onto landscapes, but for dialogue scenes, he seldom uses the extremes of lens lengths, favoring medium-range lenses like the 50mm. His camera seldom traces the arabesques of today's florid Steadicam images; apart from the digital experiment of The Book of Life (1998) his tracking shots tend to be reminiscent of the solid, heavy-camera style of the 1940s studios. Where he is most akin to his mainstream contemporaries is his reliance on fairly close views. His two-shots frequently squeeze characters into almost cramping proximity, and his disjointed and cross-purposes dialogues are often played out in medium-shots and medium-closeups, sometimes with only faces and hands visible. We shouldn't minimize the economic advantages of staging in this manner. Hartley has observed that "The less you show, the more pages you can shoot each day."[10] Yet he has turned these cost-cutting maneuvers to artistic advantage. |

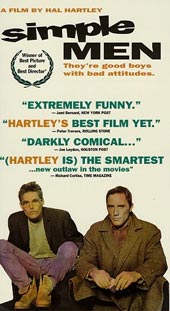

Simple Men (1992). |

||||||||||||||||||

For one thing, he achieves effects quite different from those yielded by today's standard tight close-ups. The difference is partly traceable to his proclivity for certain tactics of depth staging. During the 1940s, directors like Welles and Wyler began to explore staging which not only set characters in considerable depth but also - almost as a consequence of depth staging - turned one or both away from each other (Fig. 1). This tactic wasn't unprecedented, of course - it is common in 1910s cinema - but Welles and Wyler gave it a looming force by placing one character quite close to the camera. Hartley's debt to this tradition seems evident. In many of his dialogue scenes, characters turn from each other as they talk. "I've noticed a lot of times that we don't always look at each other, and sometimes it's much more interesting to detail the way people avoid contact than it is to detail the way people try to gain contact."[11] Quite often the characters' evasions lead them to move to the extreme foreground, favoring us with a facial view not available to their counterparts. Occasionally, the composition yields a big foreground face with other planes tapering into depth, often not in focus (Fig. 2). This sort of staging is fairly rare in today's cinema, and one might be tempted to see it as an ex-film-student's self-conscious revival of the schemas which Bazin celebrated. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

Hartley's prolonged close-ups and his insistence on keeping significant background planes out of focus complement other stylistic tactics. When characters do face one another, Hartley often avoids establishing shots and relies on the Kuleshov effect to connect his isolated actors. He has remarked: "Establishing shots tell us nothing except where we are. 'Where we are' will be elucidated entirely by what the actors are doing and experiencing."[12] Moreover, Hartley's sharply defined pieces of space aren't linked smoothly. He seldom cuts on movement, pushing matches on action to the sides of the frame, and he likes slightly high angles which don't cut together fluidly (Figs. 3-4). His one-on-one cutting often produces ellipses, signaled chiefly by jumps in the soundtrack. Hartley's emphasis on singles also yields oddly timed shot/ reverse shots. In such passages, most of today's directors cut on each significant line; this is one reason even dialogue-heavy films today have a rapid editing rate. In Hartley's films, after one character speaks, we are likely to linger on him or her while the other character replies, often at length. Or we may cut away quickly from the speaker in order to dwell the listener's reactions to a flow of offscreen lines. In Simple Men, when Bill confronts Kate near the end of a long night of partying in her tavern, Hartley presents the exchange in an irregularly paced string of shot/ reverse shots. In a medium-close-up Kate asks how long Bill will stay. In the answering shot, Bill announces that he will spend the rest of his life here. Hartley cuts back to Kate as she says, "Really" (Fig. 5) and muted solo guitar is heard. But then Bill utters a key line: "With you." Since Bill has earlier announced that he intends to meet a beautiful woman whom he will seduce and abandon, it is crucial for us to see his expression as he declares his love, so that we may gauge his sincerity. Instead, Hartley holds on Kate, putting Bill's pledge offscreen and thus maintaining an indeterminacy about his motives. Kate replies: "You seem pretty confident about that," and again Hartley keeps Bill's important reply - "I am" - offscreen. "I hardly know you," replies Kate, still in her single shot. Not until midway through Bill's next line, "Oh, you'll get to know me in time," does Hartley give us a brief, and fairly uninformative, shot of Bill completing the sentence. His final line is heard over a repeated reverse-shot of Kate (as in Fig. 5) reacting to his remark. In all, the enjambed cutting rhythm maintains mystery about Bill's motives and lets us scrutinize Kate's cautious uncertainty. Her response is weighted in another way. Of the five shots, Bill is allotted only two of them, totaling only eight seconds; Kate gets twenty-nine seconds, and the prolonged shot mentioned above alone lasts eleven seconds. The device of dividing our attention between offscreen dialogue and onscreen response becomes especially vivid in the film's final shot, when Bill's reunion with Kate is presented as a tight shot of the couple and the unseen Sheriff's voice intones: "Don't move" (Fig. 34 below). All these factors cooperate to give each image a modular, chunky weight which the rapidly refreshed close views of mainstream movies seldom achieve. "Continuity bugged me," Hartley says. "It got in the way of the image."[13] The artificiality of his dialogue and the slightly stilted, confessional performances are heightened by solid, even stolid, shots, joined by cuts which, by short-circuiting the rhythm of normal give-and-take editing, impede the flow which normal cinema seeks to provide. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

In some respects, this cluster of options seems like a less rarefied version of Bresson's technique, but it bears an even stronger resemblance to the style developed by Godard in films from Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979) onward. It is as if Godard sought to dismantle Intensified Continuity exactly while Hollywood directors were elaborating it. He will stage whole scenes in extreme partial views, thereby refusing to specify all the characters who are present or offering clues only through offscreen voices. The angles often suppress information about locale, and significant planes of action are cast into blur (Figs. 6-7). And his reverse shots, often cutting against the dramatic arc of the dialogue, may be one source of Hartley's off-the-beat image/sound rhythms. Hartley has not been shy about acknowledging his debts. "In the late 80s I became excited by the way [Godard] arranged shots in juxtaposition to sounds. That's how it began. It was graphic. I had no idea what actually occurred in Hail Mary in a concrete sense."[14] Yet Hartley's films can't be reduced to a sum of influences. "I find I'm having a kind of dialogue with Godard by trying to describe what's beautiful in his work. Of course, even if I try to imitate it, I get it wrong, because I fall into my own groove."[15] His groove channels a more replete and causally-propelled narrative, more clear-cut character motivation, greater cohesion within and between scenes, and less self-consciously poetic digressions than we find in Godard. Hartley delays or syncopates his reaction shots; Godard deletes them. Hartley's space is gappy, Godard's is fractured. One is laconic, the other is sphinxlike. Is this another way of saying that Hartley offers a domesticated version of Godard's disjunctions? While there is enough 1970s Screen sentiment still around to demand that we favor the more "radical" style, I think that we ought to recognize - in the Monogram spirit - that artists who bend innovative techniques to accessible ends can also be highly valuable. (Prokofiev comes to mind.) Hartley's intelligent blend of the trends I've mentioned (and probably others I've missed) gives his films a credible originality within contemporary cinema. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

Hartley's commitment to close views, depth compositions, and partial revelation of a scene's space have led him toward a delicacy of staging which his contemporaries, mainstream or indie, seldom undertake. The first shot of Simple Men, a 51-second take showing a robbery, is arranged with a flagrant precision (Fig. 8). Another early scene affords us a chance to see how Hartley creatively revises some pictorial schemas circulating in both European and American cinema. In a coffee shop, Bill meets his ex-wife Mary after the holdup and gives her the money which Vera and her double-crossing paramour have tossed at him. In the course of the scene, Bill learns that his father has been arrested and that Mary has found a new lover. Hartley provides no establishing shot, and he packs his frame with close views of his players. Across its four shots, three of them quite long takes, the scene unfolds as a series of deflected glances, with Bill and Mary persistently looking away from one another. In addition, the tight framings allow Hartley to create a rhyming choreography of frame entrances and exits, along with a few small spatial surprises. At the outset Mary is seen in medium-shot; as she turns, Bill slides in behind her (Fig. 9). We are at a counter by a window. As in Godard's films, no long shot lays out the space, and Bill's arrival in the frame is not primed by a shot of him entering the coffee shop. The shot activates greater depth as a waitress's face appears in a new layer of space and Bill orders coffee (Fig. 10). Mary shows Bill the newspaper story about his father's capture, looking at him for the first time (Fig. 11), but Bill ignores her, and we hold on her as he walks out of the shot reading the paper (Fig. 12). |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Bill had entered Mary's shot, but now she enters his, as he stands reading the paper near the (offscreen) front counter (Fig. 13). The frame placements are reversed from the first shot; Bill in the foreground turns away from her insistently as Mary talks to the offscreen waitress, who praises "William McCabe, the radical shortstop" (Figs. 14-15). And as Bill had left Mary's shot, now she leaves his, giving him time to peel off the money he will give her for his child (Fig. 16). As in the Intensified Continuity style, hand movements and props must be brought up to the actor's face if we are to see them. |

* Betegnelse fra baseball: markspiller mellem anden og tredje basemand. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Track back with Bill to the window counter, where he rejoins Mary in a slightly more distant framing than the first shot had afforded. Throughout that earlier shot, a man had been sitting at the counter in the background out of focus, and the new framing makes him somewhat more prominent. At this point Mary refers to her new man, gesturing (Fig. 17); we are prepared to identify him as the man in the background. But Bill's look activates a quite different offscreen zone (Fig. 18). Using the Kuleshov effect, Hartley cuts to a glowering man in a bandanna at the pinball machine (Fig.19). Coming after prolonged shots of the couple, this single phlegmatic cutaway has an almost comic effect, as if a new piece of Mary's situation were striking Bill with a thud. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fig.19. |

||||||||||||||||||

The fourth shot continues the setup of Bill and Mary at the counter, replaying the turned-away postures that have dominated the scene. Bill passes Mary the money, saying it should go to their boy (Fig. 20). After he glares at her for an instant, she throws his bad conscience back at him, and he grabs her (Fig. 21). Now, for significantly longer than just before, they are facing each other and exchanging direct looks. Then Mary tears herself away (Fig. 22) and the waitress brings Bill the doughnut Mary had ordered (Fig. 23). Where can the shot go now? One possibility is a dialogue with the now-curious man in the background, cued once more as Bill gestures vainly with the plate on which a doughnut sits (Fig. 24). Instead Hartley springs another quiet surprise. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fig.24. |

||||||||||||||||||

As Bill ponders the doughnut, Mary and her boyfriend are visible outside the window, talking to a figure seen from the rear (Fig. 25). ("The back of someone's head," Hartley wrote in a 1987 note, "is part of that person too, worthy and necessary to be seen."[16]) Hartley calls our attention to this zone by having Bill turn (Fig. 26), then studiously ignore his brother Dennis at the window (Fig. 27). Eventually Dennis enters. In a compressed replay of the Bill-Mary exchange, Bill launches an oblique dialogue with Dennis, at first indifferent (Fig. 28) and then, when Dennis tells him that their father is in the hospital, facing him directly (Fig. 29). It is on this note that the shot ends. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fig.29. |

||||||||||||||||||

The rhythmic entrances and exits of figures recall Antonioni's 1950s films, as does the avoidance of shared looks. Beneath their indifference to one another, the characters guardedly probe each other's feelings, and these states of mind are expressed through crisscrossing patterns of movement. "I watch Antonioni more closely and with greater appreciation now than at the time I made Simple Men or when I was introduced to him at school. But I remember I was always struck by work of that kind of artfully constructed blocking, the interaction of the actors' movements with the camera movement."[17] Still, in this scene and others Hartley makes the technique his own. For one thing, the proximity of the characters to the camera accords with the premises of intensified continuity; not for Hartley the distant, often opaque landscapes and interiors of Antonioni's work. Yet while mainstream US filmmakers use the close framings in order to show characters' eyes locking onto one another, Hartley shows us fleeting eye contacts. Each of these comes as a distinct beat, marking a moment in the drama. He could not punctuate his scenes this way if he were more "radically" Godardian, for in Godard's uncommunicative découpage we are often not sure when anybody is looking at anybody else. The choreography played out in the coffee shop finds one contrasting climax later when Bill, now on the run, becomes attracted to the café-keeper Kate. Slightly drunk, he vows to stay with her in the shot/reverse-shot sequence I've already mentioned. Now he sits down in a chair, angled slightly away from her (Fig. 30). At first she resolutely won't return his look. Then, for nearly 100 seconds, they stare mesmerically at each other as they talk about who's seducing whom (Fig. 31). Asked about this blocking, Hartley replies: "The logic I used had to do with the flirting they were involved in, almost two animals circling each other."[18] During this, perhaps the film's most erotically charged exchange, the camera winds around them in a subdued variant of an intensified-continuity spiral before moving in slightly as they kiss (Fig. 32). Immediately, however, Kate leaves the frame (Fig. 33). |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

In a film where characters tell each other that there is only "trouble and desire," we see a dance of attraction, hesitation, and abrupt breakoff. It is played out in the way bodies and faces, often cast adrift from their wider surroundings, warily shift in and out of view. The figures may align but more often they split apart, with Hartley consigning them to backgrounds or to separate shots before the rondelay starts again. When the thrust-and-parry dialogue fades, eye contact helps mark the rare moments of emotional synchronization. The dance of glances and bodies continues to the very end. Bill, one of the simple men, has returned to be arrested, but he throws off the deputies and advances toward Kate. A shot/reverse-shot sequence captures their shared look, but in their last shot, their eyes don't meet. Bill's face slides into the frame to nestle against Kate's chest (Fig. 34). Hartley isn't the only indie filmmaker attracted to a mix of poker-faced absurdism and unabashed romanticism. His tone echoes Alan Rudolph's work, particularly Choose Me (1984) and Trouble in Mind (1985), and has parallels in Paul Thomas Anderson's Punch-Drunk Love (2002), which seems structurally a Hartley film. But Hartley's style in Simple Men remains idiosyncratic, selecting and reworking schemas ranging from Hollywood to Godard. Most filmmakers can be understood as tied to traditions in just such ways, as Monogram noted. Across three decades Thomas Elsaesser has reminded us, in pages which will inspire reflection for many years, that in order to understand the art of cinema we must nurture in ourselves an awareness of the varied and unpredictable forces of history. |

Fig.34. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|