Like my ‘169 Seconds: 2008 – A Crisis Glossary’, published in this journal, ‘Classif. & Me (Laird’s Constraint)’ is an outtake, focussing on the 2015 feature The Big Short (dir. Adam McKay), from work on films on the 2008 financial crisis (O’Leary 2023). The occasion for making ‘Classif. & Me’ was a series of exercises designed and shared by Ariel Avissar during the summer of 2024, in which videographic practitioners were invited to create videos according to sets of constraints derived from existing video essays. (Many of the resulting exercises from this ‘Parametric Summer’ series have been made available in Vimeo showcases linked to in Avissar 2024.) The rationale for these exercises was that certain video essays offer not just an effective analysis of the audiovisual objects or phenomena with which they are concerned, but also provide a form that other videographic practitioners can adopt for their own purposes (O’Leary 2020).

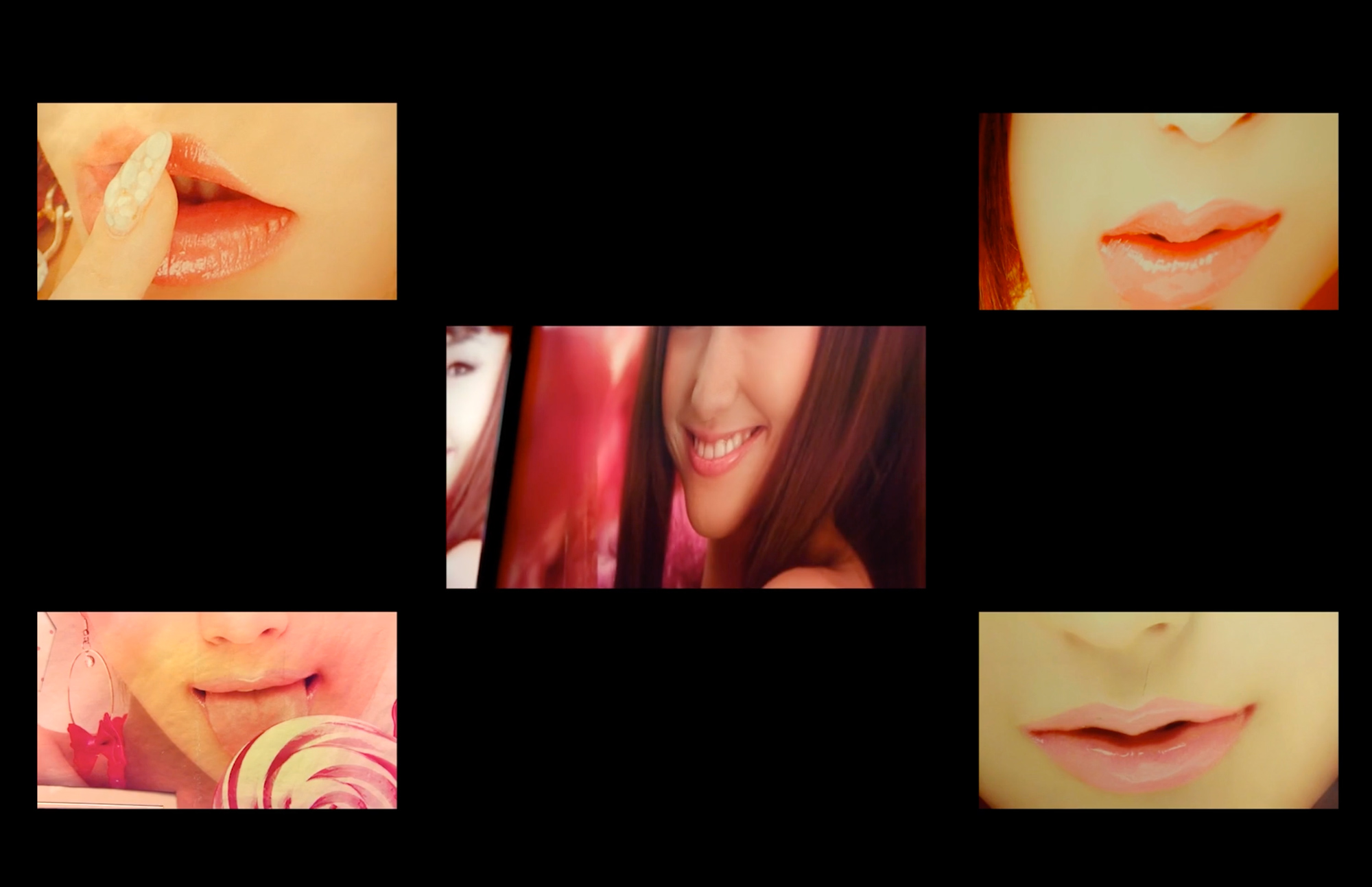

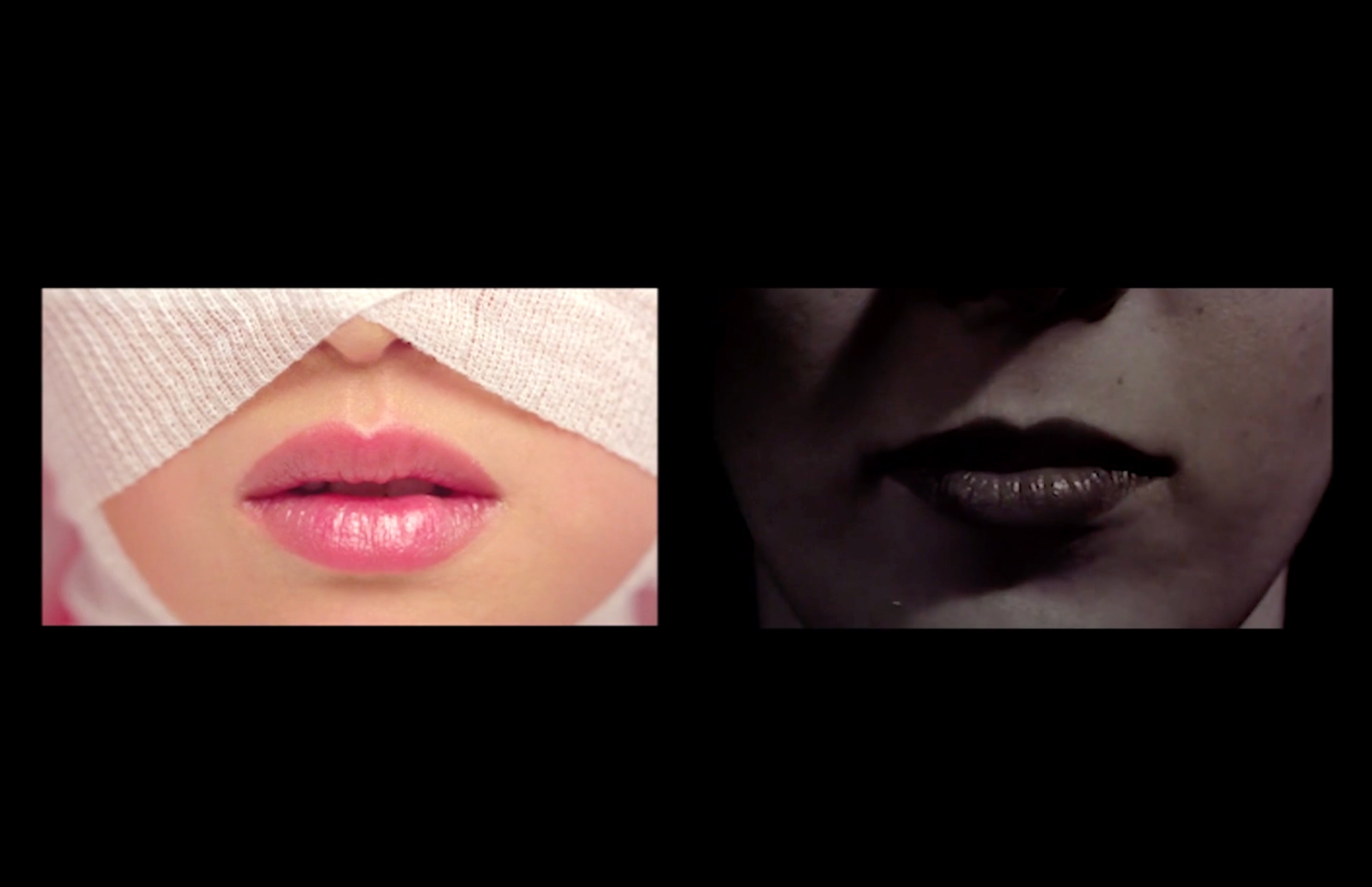

‘Classif. & Me (Laird’s Constraint)’ was made in response to the set of constraints that Avissar extracted from ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ (Laird 2023), a virtuoso video essay by Colleen Laird about Japanese director Ninagawa Mika’s Helter Skelter (2012). In its first half, ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ performs an intensive analysis of the Helter Skelter’s opening montage (fig. 1-2). Laird writes that ‘the montage of 146 shots familiarizes the audience with the film’s female protagonist, contemporary Japanese cosmetics culture, the Japanese commercial photography industry, the Shinjuku high fashion district of Tokyo, and various gendered consumption practices all tied to the body, the politics of looking, and the construction and representation of one’s outward-facing visual self’ (from the creator statement in Laird 2023). Laird decomposes and visually categorizes the 146 shots using a complex multiscreen dispositif, while, in the second half of the video essay, she juxtaposes images from Helter Skelter with the title sequence from Vertigo (1958) (fig.3). As Laird writes, ‘the similarities to Hitchcock’s Vertigo highlight the role of the camera in [Ninagawa’s] work and the constant self-assertion of the Ninagawa persona at the fore of it all’ (from the creator statement in Laird 2023).

Avissar extracted a detailed set of parameters from ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ for the Laird’s Constraint exercise. I won’t repeat these lengthy instructions here (they can be found in Avissar 2024), but the constraint involved mimicking the techniques used by Laird (fast motion, still frames, dynamic multiscreen grids, etc.) to introduce and analyse a montage sequence of one’s own choosing, and to categorise the individual shots in the chosen sequence. Audio could be derived from any source, but the instructions capriciously stipulated that the film containing the montage sequence had to be put into ‘some sort of dialogue’ with another audiovisual object from ‘precisely fifty-four years before or after the media object from which your montage sequence is taken’ (fifty-four years being the gap between the releases of Vertigo and Helter Skelter).

It was both technically and conceptually challenging to imitate the virtuoso performance of ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ in my own analysis of the opening montage (or is it two montages?) from The Big Short. As can be inferred from the description above, Colleen Laird’s videographic apparatus in ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ was developed for a particular analytical purpose, and in response to a unique film and its distinctive director. I felt I couldn’t claim the same sympathetic investment or analytical confidence that ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ displays vis-à-vis its source material. But riffing on ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’ in ‘Classif. & Me’ allowed me to express, in a playful and ambivalent way that ironizes my own scholarly persona, a set of ongoing concerns about the nature of videographic enquiry in what might be dubbed the age of the attainable text.

I wanted, that is, to refuse a certain sort of ‘scientific’ authority. I did follow Avissar’s instructions for Laird’s Constraint more or less scrupulously — for example, by using music from films released in 1961, fifty-four years before The Big Short. But rather than aiming to mimic Laird’s analytic precision in ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’, I tried in ‘Classif. & Me’ to make subjectivity and error into structuring principles. The file card visual motif used in the centre of the video essay, for example, was improvised after I realised I had miscalculated the number of individual shots from The Big Short montage to be included on each horizontal of the multiscreen grid. Rather than redoing the grid, I introduced a visual ‘tab’ to occupy the space on the top horizontal where the missing thumbnails should be, and then shifted the tab (and some of the thumbnails) for each subsequent ‘file card’ and whimsical classification (fig.4). Other errors have been allowed to stand in the video essay even when not especially structural. One example is the image of an older man with the invitation ‘How may I help you?’ emblazoned on the back of his vest. I had assumed he was a government employee and ‘classified’ him as such, but an American colleague pointed out that, actually, he was likely working for the retail chain Walmart, which had scooped up a surplus of newly-needy seniors suffering after the 2008 crash to perform menial roles for minimum wage. I have left the mistake intact precisely to point to the absurdity that the act of classification may often perform or disavow.

Absurdism is the register of ‘Classif. & Me’, which adduces Borges and Foucault to acknowledge the cultural specificity of the ordering of things, an acknowledgement which does not exempt videographic criticism. Now that, with the advent of digital files and consumer editing software, we have realised Bellour’s dream of the attainable text, videographic film scholars could succumb to a positivistic conviction of the exhaustive knowability of the film object. ‘Classif. & Me’, in its facetious way, is a protest against that conviction.

Facts

Films

- The Big Short (dir. Adam McKay, 2015)

- Helter Skelter (dir. Ninagawa Mika, 2012)

- Vertigo (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Literature

- Avissar, Ariel (2024), ‘2024 Parametric Summer Series – Exercise Prompts’. Available here.

- Bellour, Raymond (1975), ‘The Unattainable Text’, Screen 16:3, 19-28.

- Borges, Jorge Luis (1952), ‘El idioma analítico de John Wilkins’, in Borges, Otras Inquisiciones (1937–1952) (Sur), 139-144.

- Foucault, Michel (1966). Les Mots et Les Choses (Éditions Gallimard)

- Laird, Colleen (2023), ‘Eye-Camera-Ninagawa’, [in]Transition 10: 2.

- O’Leary, Alan (2020), ‘Payne’s Constraint: On Matt Payne’s “Who Ever Heard…?”’, Notes on Videographic Criticism, 11 July.

- _______(2023), ‘Men Shouting: A History in 7 Episodes’, [in]Transition 10: 2.